New findings from a large randomized breast screening trial in the U.K. show that there is a mortality benefit if screening starts when women are in their 40s. But that benefit seems to fade over time, according to a study published on 12 August in the Lancet Oncology.

The study included data from more than 160,000 women who participated in the U.K. Breast Screening Age Trial, a randomized trial that compared breast cancer mortality outcomes prior to patients' first breast screening.

"The benefit is seen mostly in the first 10 years, but the reduction in mortality persists in the long term at about one life saved per thousand women screened," stated lead author Stephen Duffy, professor of cancer screening at the Queen Mary University of London Centre for Cancer Prevention, in a press release.

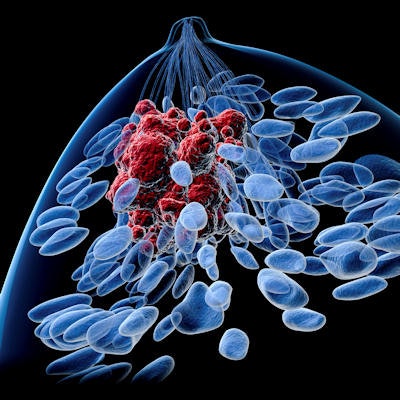

Breast screening programs help to save lives by identifying cancer early when patients are most likely to experience positive treatment outcomes. The U.K.'s National Health Service (NHS) program achieves this aim by offering screening to women every three years starting at age 50.

The authors wondered whether long-term outcomes would improve if breast screening instead started at age 40 or 41. To find out, they recruited 160,000 women in the UK who were between the ages of 39 and 41 in 1990-1997.

Trial participants were randomized into two groups and followed for 23 years. The first group underwent annual mammography starting at age of 40 or 41 before aging into the regular NHS screening program at age 50. Meanwhile, the second group only participated in the regular NHS program starting at age 50.

The researchers found that at the 10-year follow-up point, women who participated in annual screening before age 50 had a 25% lower relative risk of dying of breast cancer -- a difference that was statistically significant. But that difference disappeared at follow-up points later than 10 years.

| Impact of breast screening on mortality based on age at start | ||||||

| Years at follow-up | Screening starts at 40

(n = 53,883) |

Screening starts at 50

(n = 106,932) |

Risk ratio | P value | ||

| Deaths | Death rate | Deaths | Death rate | |||

| 1-9 | 83 | 0.15% | 219 | 0.2% | 0.75 | 0.029 |

| 10+ | 126 | 0.234% | 255 | 0.238% | 0.98 | 0.086 |

The authors calculated that early screening saved 11.5 years of life per 1,000 women screening -- or 620 years of life total. Also, the authors calculated that 1,150 women ages 40-49 would need to be screened to prevent one breast cancer death.

In their discussion of the findings, the authors noted that their results were consistent with a recent meta-analysis of randomized mammography trials -- although one key difference with the current study was that all of the screening in the current study started before age 50.

They speculated that the absence of a statistically significant mortality benefit at the longer follow-up period was due to a reduced effect of earlier screening on grade 3 tumors, in which some breast cancers were postponed rather than prevented. They also pointed out that the screening period spans the 1990s and early 2000s, using film-screen mammography with single views. Considerable changes in screening, diagnosis, and therapy have occurred since then.

Based on their findings, the authors concluded that reducing the breast cancer screening age in the U.K. could potentially save lives. They called for future research to study whether better technologies and treatments might further improve breast cancer outcomes for women screened between the ages of 40 and 49.

"This is a very long-term follow-up of a study which confirms that screening in women under 50 can save lives," Duffy stated. "We now screen more thoroughly and with better equipment than in the 1990s when most of the screening in this trial took place, so the benefits may be greater than we've seen in this study."