A new CT study of the 3,000-year-old "mummy of the screaming woman" in Egypt has investigated whether the shocking facial expression of pain was due to the heart attack that might have caused the woman's death or due to postmortem changes. The group's analysis has already generated considerable debate.

The mummified ancient Egyptian princess was discovered in 1881 at the Royal Cache in Deir el-Bahari, Thebes (now Luxor). The CT study of the mummy revealed that severe atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries led to sudden death of the Egyptian princess with a heart attack, according to joint authors Zahi Hawass, PhD, the well-known archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, and Dr. Sahar Saleem, a professor of radiology at Cairo University who specializes in CT mummy imaging.

The ancient Egyptian embalming process preserved the posture of the princess at the moment of death, they explained in an article published online on 27 July by the Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine.

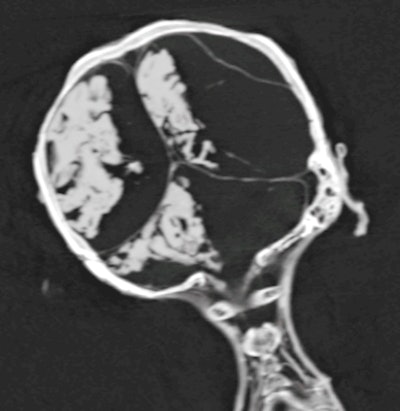

Photo of the head and upper torso of the mummy known as "Unknown Woman A," taken on 9 March 2020. It shows widely opened mouth and tilted head of the mummy to the right side. All images courtesy of Dr. Sahar Saleem and Dr. Zahi Hawass.

Photo of the head and upper torso of the mummy known as "Unknown Woman A," taken on 9 March 2020. It shows widely opened mouth and tilted head of the mummy to the right side. All images courtesy of Dr. Sahar Saleem and Dr. Zahi Hawass. 3D CT image shows extensive dental attrition and periodontitis.

3D CT image shows extensive dental attrition and periodontitis.The CT findings indicate that the mummy designated "Unknown Woman A" died in her 50s (sixth decade of life) and suffered from advanced diffuse atherosclerosis and severe coronary heart disease, Saleem. Unknown Woman A was well mummified and eviscerated, and her body cavity was filled with resin. The desiccated brain had shifted to the right inside her skull.

"This is the first mummy with forensic evidence of death circumstances suggesting that her cause of death was sudden severe heart attack," Saleem told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "It is the first study to suggest the cause of death of an ancient Egyptian full Mummy to be sudden death caused by a severe heart attack evident by forensic circumstances, mummification findings, and pathological imaging results."

Coronal CT image of the head and neck of mummy shows the desiccated brain shifted to the right side of the cranial cavity.

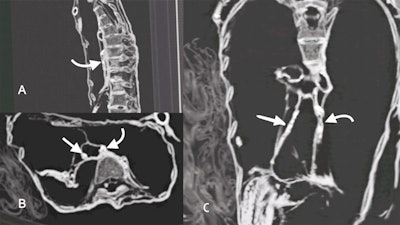

Coronal CT image of the head and neck of mummy shows the desiccated brain shifted to the right side of the cranial cavity. Compiled CT images of Unknown-Woman-A mummy torso in sagittal plane (A), axial plane (B), and coronal plane (C). Presence of high-density calcifications within the course of the right coronary (straight arrow) and left coronary arteries (curved arrows) in multiple planes indicate severe atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries.

Compiled CT images of Unknown-Woman-A mummy torso in sagittal plane (A), axial plane (B), and coronal plane (C). Presence of high-density calcifications within the course of the right coronary (straight arrow) and left coronary arteries (curved arrows) in multiple planes indicate severe atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries.The CT scan have provided useful information about the woman, including her mummification style, underlying advanced cardiovascular atherosclerosis disease, and her possible death circumstances, added Saleem, who is a fellow at the University of Western Ontario in Canada. "The circumstances suggest that she possibly died from sudden and massive myocardial infarction. Death spasm preserved the unusual posture, and the contracted body was apparently mummified before relaxing her postmortem position."

The original discovery

Two mummies were found in the Royal Cache: a woman and a man, both of whom had their mouths widely opened as if they were screaming, the authors wrote. The mummies were transferred to Cairo Egyptian Museum to be examined by Gaston Maspero, then head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

The identity of the mummies could not be settled, so Maspero assigned them letters and named them "Unknown Woman A" and "Unknown Man E." The latter was recently identified as Pentawere, the 20th Dynasty prince who was executed for conspiring against the life of his father Ramesses III in what is known as the Harem Conspiracy.

On 30 June 1886, Maspero examined Unknown Woman A and recorded on her wraps the following inscriptions in hieratic writing: Royal daughter, royal sister Meritamun. However, the mummy was considered unknown, as there were several princesses named Meritamun, including the daughter of Seqenenre Taa II (1,558-1,553 B.C.) from the end of the 17th Dynasty, as well as the daughter of Ramesses II (1,279-1,213 B.C.) from the 19th Dynasty.

In 1902, Grafton Elliot Smith, the professor of anatomy, examined Unknown Woman A and described her as a roughly embalmed small-frame old woman with tilted head to the right side, widely opened mouth, and slightly flexed legs crossed at the ankles. Maspero and Smith considered that her facial expression and posture were unusual and that she might have died in agony.

CT findings

On 9 March 2020, the mummy was transferred to the CT unit (Somatom Emotion 6 from Siemens) installed in a truck in the garden of the Egyptian Museum. To provide support, foam blocks were placed under the mummy's tilted neck and flexed knees.

Dr. Sahar Saleem looks closely at the mummy on the CT scanner table.

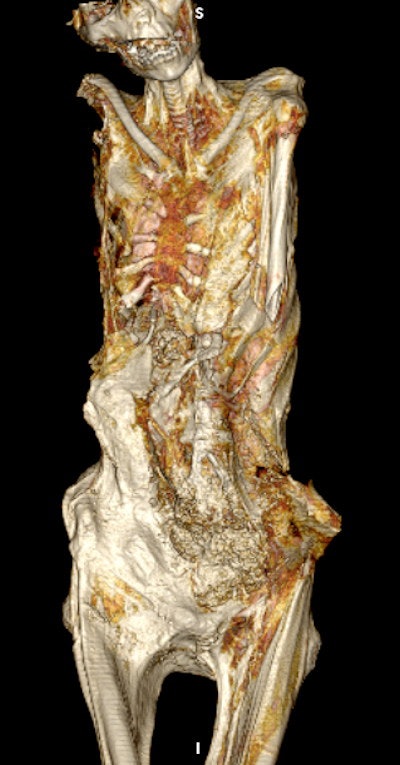

Dr. Sahar Saleem looks closely at the mummy on the CT scanner table."The mummy is poorly preserved. There is a big defect in the anterior abdominal wall, likely inflicted postmortem by ancient tomb robbers. There is a gaping left inguinal embalming incision. Right upper limb and left forearm are missing. The toes of left foot are disarticulated, while toes of right foot are missing," the authors wrote.

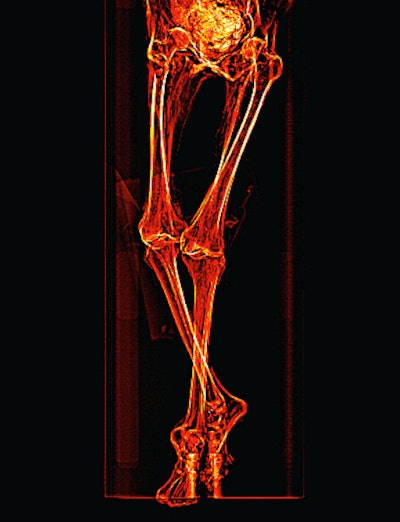

Saleem obtained maximum length measurements of the major long bones. The right femur measured 402 mm, left femur 401 mm, right tibia 338 mm, left tibia 338 mm, right fibula 338 mm, and left fibula 339 mm. Because of the oblique posture of the mummy, it was impossible to obtain a vertex-to-heel measurement. The stature was estimated to be about 151 cm ± 2.5 cm based from the femur length using regression equation derived for ancient female Egyptians.

3D CT image of the upper body of the mummy shows the gaping left inguinal evisceration incision. The disrupted anterior abdominal wall (likely inflicted by tomb robbers) reveals embalming material packs within the body cavity.

3D CT image of the upper body of the mummy shows the gaping left inguinal evisceration incision. The disrupted anterior abdominal wall (likely inflicted by tomb robbers) reveals embalming material packs within the body cavity.3D CT images of the mummy documented the tilted head position, while 2D CT image showed intactness of the skull base, without any attempt of brain removal. The desiccated shrunken brain is seen in the CT images shifted to the right side of the cranial cavity. No resin or other embalming materials are seen within the cranial cavity.

There is evidence of evisceration through a left flank incision, Saleem reported. The abdominal and pelvic cavities are stuffed with packs of variable CT densities denoting linen (-100 HU) and resin (70 to 120 HU). The heart, trachea, and large vessels are detected in the thorax. No amulets or jewelry are seen within the body cavity or on the mummy's body surface, and no subcutaneous packing or artificial eyes are seen.

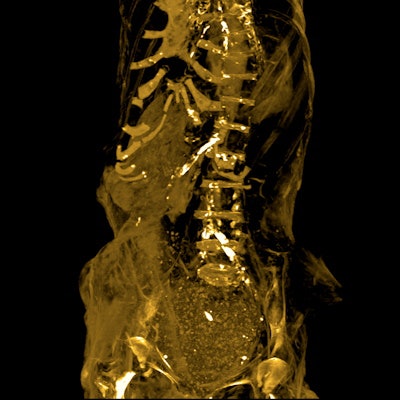

Maximum intensity projection image of the mummy's torso shows the arteries and tissues.

Maximum intensity projection image of the mummy's torso shows the arteries and tissues. Scout CT scan shows the mummy's legs are partly flexed and crossing at the ankles, with the left leg above the right.

Scout CT scan shows the mummy's legs are partly flexed and crossing at the ankles, with the left leg above the right.She noted that definite atherosclerotic changes are visible as high-density areas of calcification within the walls of identifiable arteries: right and left carotid bulbs, right and left coronary arteries, abdominal aorta, superior mesenteric artery, coeliac artery, bilateral iliac, femoral and peripheral leg arteries. Also evident was mild lateral curvature of the dorsal spine with its convexity to the left (scoliosis); no structural abnormalities of the spine or anomalous vertebrae could be seen.

"We assume that the dead body of 'Unknown-Woman-A' might not have been discovered until a few hours later, enough to develop postmortem spasm. We assume that the embalmers likely mummified the contracted body of 'Unknown-Woman-A' before it decomposed or relaxed, thus preserving the posture her body took when she died," wrote Hawass and Saleem.

Doubts emerge

One source has already voiced scepticism about the study, however.

"Our group has CT scanned over 300 mummies now, and it is almost never possible to determine the exact cause of death from the CT scan," Dr. Randall Thompson, a cardiologist from St. Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, told Gizmodo UK, the technology and science website.

He pointed to two exceptions: A Mongolian mummy with a noose around his neck and an Egyptian mummy with an arrowhead lodged in his chest cavity and what appears to be a significant amount of mummified blood.

"The medical doctors on our team observed with some amusement that museum curators and anthropologists sometimes spin a whole story about a mummy from a small piece of objective data -- and there is no one around to contradict them," he said to Gizmodo. As for the alleged death pose, he said an "open mouth in a mummy is almost certainly a postmortem change, and not an expression of emotion frozen at the time of death."

The authors respond

In her response sent to AuntMinnieEurope.com on 29 July, Saleem said she thought Thompson had "rushed to this faulty conclusion" because he had not read the full scientific paper.

"In our report, we adopted the opinion of the paleopathologist Arthur Aufderheide that the screaming facial appearance of a screaming mummy was postmortem changes rather than due to emotional state at death. In the discussion section, we clearly say: 'We assume that the mouth opening of 'Unknown-Woman-A' mummy was rather due to the normal jaw drop of the dead,' " she noted.

She added that they used sound scientific methods. They consulted with three eminent experts, who revised the results of the research, and then submitted the manuscript to a peer-reviewed journal. Also, Saleem said she has been the leading paleoradiologist of the Egyptian Royal Mummy project of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and for several other major mummy projects and museums in Egypt and the world, and she noted that she has used CT and x-ray to examine several hundred Ancient Egyptian mummies, 50 of whom were royals.

In their previous studies of the royal mummies, Hawass and Saleem have found the cause of death of several mummies, including Ramesses III, Pentawere, and Thutmose I, and soon they plan to publish details about Seqenenre Taa II, she pointed out.

"It can be difficult to reveal the cause of death using CT scans of mummified bodies who died thousands of years ago," Saleem conceded. "Many mummies, especially nonroyals, may have been poorly mummified, or their bodies were subjected to vandalism. The ancient Egyptian embalmers removed the viscera from the body, so it may not be possible to reveal causes of death due to internal organs."

"The embalmers believed that the heart was the house of the soul, so they left it inside the chest; so with a CT scan of the mummy it is possible to detect diseases like atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease as a possible cause of death," she added.

The authors are keen to conduct further studies about mummification in ancient Egypt, based on the recent discoveries from the Saqqara Mummification Workshop, of which Saleem is a member of the scientific team. They hope such investigations can increase understanding of the postmortem changes like death spasm and the effect of mummification.