Scientific interest in the study of mummies increased at the end of the 19th century. The first images of mummies were taken shortly after the discovery of x-rays by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in 1895. Physicist Carl Georg Walter König described the x-ray of the knee joints of a mummy of a child and that of an Egyptian cat, in an article published in 1896. This analysis was a milestone. In the early days, x-rays were mainly used to identify false mummies and to nondestructively detect burial objects in bodies and bandages.

Investigations of the royal mummy of Thutmose IV -- the eighth Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled in approximately the 14th century B.C. -- initiated x-ray examinations of the other mummies of the Egyptian pharaohs in 1903.

The dried-out remains of the brain of the mummy of Nakht (scribe and astronomer of Amun), kept at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, were first scanned in 1976.

The first full-body CT scan of a mummy, Djedmaatesankh (a middle-class Theban woman who died in the ninth century B.C.), followed soon afterward. Since then, medical imaging systems in mummy research have undergone continuous technical optimization.

X-ray imaging systems allow a nondestructive look inside the mummies, the intention being to document the state of preservation of the skeleton and soft tissues, to determine sex and age, as well as to identify pathologies and the cause of death. It can also detect evidence of surgeries, artificial manipulations, and foreign bodies. CT shows any structure of a body in cross-sectional images without superimposition and with high spatial resolution (slice thicknesses up to 0.4 mm, depending on the equipment), the acquisition is done in a few seconds. The dual-energy CT scanner introduced in 2006 works with two detection systems perpendicular to each other. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional images of skeletons and tissues can be reconstructed from the CT data for analysis at any time.

Case 1:

All images courtesy of the German Mummy Project (GMP) and JFR e-Quotidien.

All images courtesy of the German Mummy Project (GMP) and JFR e-Quotidien.A child mummy, currently in the collection of the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt am Main, was the first human mummy to be x-rayed in a nondestructive mummy study. Carl Georg Walter König x-rayed the knee joints in a laboratory of the German Physical Society in 1896. In 2016, the mummy was again studied by the GMP research team. The exact provenance of this mummy acquired by an explorer in Egypt in 1817 is unknown. Dating revealed that the child lived in the early Greco-Roman period (378 to 235 B.C.). CT examinations provided detailed results. This is a 4- to 5-year-old boy whose organs were not removed. His sternum has a congenital S-shaped concavity (pectus excavatum). An enlarged liver can be a sign of a schistosomiasis-like infection, which can cause fever, body aches, fatigue, and allergic reactions. It is not known whether the boy died of such a disease.

Case 2: An old criminal case

Another GMP file concerns ancient Egypt. It is a mummified head with red hair from the collection at the National Museum of History and Art in Luxembourg. Radiocarbon dating revealed that this individual lived in Roman times (17 B.C. to 124 A.D.). A CT scan showed that the head belonged to a 25- to 35-year-old woman. The skull, under the intact scalp, shows an occipital fracture, which must have occurred shortly before her death. The shape and location of the fracture as well as the absence of signs of healing suggest that a blow with a blunt object caused the woman's death. The woman was murdered about 2,000 years ago.

Case 3:

The "Cross-Legged Woman" mummy is part of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museum's collection and was once completely wrapped in textiles. Radiocarbon dating revealed that the woman lived between A.D. 1390 and A.D. 1460. Mummies lying down, with their legs crossed, have been discovered on the central coast of Peru, among other places, at the site of the Ancón necropolis. Funeral objects are indicative of an affiliation with the Chancay culture. A genetic analysis confirmed the South American provenance of the mummy.

Case 4:

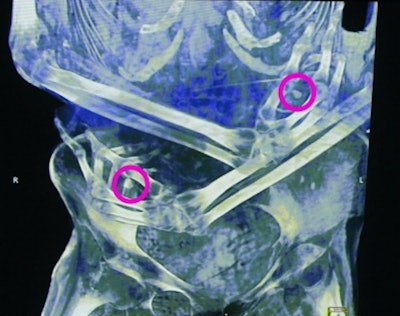

Dental condition and various skeletal characteristics were used to determine the age of this woman, with artificial cranial deformity, at between 20 and 40 years of age. Her left collarbone was fractured and poorly consolidated. Some thoracic and lumbar vertebrae show signs of tuberculosis. Calcifications in the lung tissue are also indicative of this infectious disease. CT scan also revealed two objects, approximately 1 cm in size, placed in her hands. The size and shape of the 3D printed replicas reveal that they are human milk teeth. The reason for their presence is unknown.

Case 5:

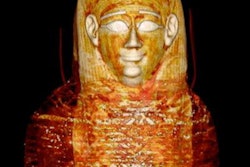

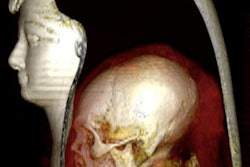

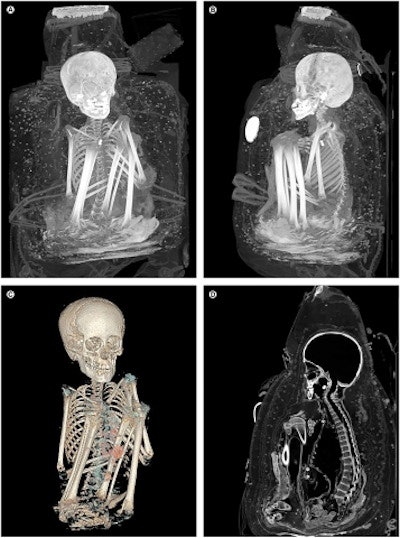

The last example concerns a packaged mummy with a so-called false head, from the Museum of Cultures in Basel. The checkered tunic is a typical garment of an officer of the Inca culture (1450-1533 A.D.). Radiocarbon dating of a fiber sample (A.D. 1480-1650) confirmed the era. A cut on the back of the tunic suggests that the mummy was manipulated by tomb robbers who dressed it in typical Inca clothing, perhaps to make it more attractive to buyers. A CT scan revealed that the boy, placed in a sitting position, was 7 to 9 years old. Traces of several diseases have been identified: A hereditary multiorgan disease (neurofibromatosis type 1) which caused changes in the skin and neural pathways. A parasitic infection such as Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease) transmitted by bug bite is also suspected. Calcifications in the lungs indicate pneumonia or tuberculosis. Trauma to the chest and abdominal walls reveals a violent death. The reasons remain speculative.

Conclusion

These examples and many others show that today's research on mummies is inconceivable without recourse to modern radiological means.

Wilfried Rosendahl is a bioarchaeologist, geoscientist, and cultural manager, general director of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museum in Mannheim, and honorary professor at the Institute of History at the University of Mannheim, Germany. Dr. Stephanie Panzer is a radiologist at the Murnau Trauma Center Murnau, Murnau, Germany. Stephanie Zesch is researcher at the German Mummy Project, Reiss-Engelhorn-Museum, Mannheim.

Editor's note: This is an edited version of a translation of an article published in French online on 8 October 2021 by the daily newspaper, e-Quotidien, of Journées Francophones de Radiologie (JFR). Translation by Frances Rylands-Monk. To read the original version, go to the JFR website.