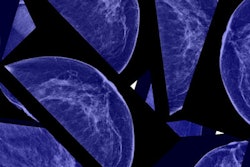

New European guidelines recommend that women be screened for breast cancer from ages 45 to 74 every two to three years because annual screening may be more harmful than beneficial. The guidelines pose a stark contrast to U.S. recommendations, which for the most part recommend annual screening.

An international panel of 28 multidisciplinary members comprised the European Commission Initiative on Breast Cancer (ECIBC) Contributor Group. The members crafted questions and corresponding recommendations for breast cancer screening to form European guidelines published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on 26 November 2019.

The ECIBC provided 15 key recommendations on how to handle breast cancer screening in terms of when to start, the frequency, and the use of additional tests such as ultrasound and MRI.

The recommendations

In Europe, instead of cohesive guidance for the entire continent, breast cancer screening is country-specific. Since 2003, the European Council has pushed for uniform, organized, population-based screening for Europe as a whole.

Since the last edition of the European Guidelines for Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis was published in 2006, new evidence surrounding breast cancer and innovation has emerged, prompting the ECIBC to develop new evidence-based recommendations -- in short, the European Breast Guidelines.

The European Commission authorized systematic reviews up to March 2016 for earlier recommendations and to December 2018 for later, more recent recommendations. The evidence informed the criteria in the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) used to develop these recommendations.

The recommendations primarily address women at average risk for breast cancer without increased risk due to BRCA genes, reproductive history, or race/ethnicity.

Recommendation 1: Do not screen asymptomatic women ages 40 to 44 who have an average risk for breast cancer.

The authors were concerned about the number of false positives in these women, as well as the radiation risk imposed by screening.

"The balance of desirable versus undesirable health effects for starting screening at age 40 probably favors no screening," they wrote.

Recommendations 2-4: Screen asymptomatic women ages 45 to 74. The panel strongly recommends organized screening for this age group but emphasized that all invited women should "receive clear information about the desirable and undesirable effects to make informed decisions."

In addition, for women ages 70 to 74, concerns have been raised about lead-time bias, the small number of women in this age bracket included for the outcome of mastectomy, and the available data for overdiagnosis derived exclusively from women ages 50 to 69 for an overall judgment of probable net health benefit. However, the group still came out in favor of screening women ages 70 to 74.

Recommendations 5-9: Women ages 45 to 49 should be screened biennially or triennially over annually. Women ages 50 to 69 should be screened biennially. However, women 70 and older should be screened triennially.

The breast panel compared screening frequency by looking at a variety of randomized controlled trials, as well as using its own modeling. For example, the members calculated events by subtracting the estimated outcome rates in women ages 45 to 69 (or 70 to 74 years) from those ages 50 to 69 (or 70 to 74) -- and assumed effects were incremental to those found for women ages 50 to 69 (or 70 to 74) at screening.

For all age groups, annual screening reduced breast cancer mortality and showed lower interval cancer rates. However, annual screening also boosted overdiagnosis, false positives, and follow-ups with biopsies. What's more, annual screening carries a higher probability of radiation-induced breast cancer rates (6 in 100,000 versus 4 in 100,000 for biennial). For these reasons, the panel recommends biennial or triennial screening over annual screening.

Recommendations 10-11: Women ages 50 to 59 should be screened using digital mammography versus digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) -- including DBT with synthesized 2D images.

Although screening with DBT increased breast cancer detection compared with digital mammography, no differences were found in interval cancer detection, recall, or false-positive recall rates. Also, moving to DBT for screening comes with costs -- both in terms of equipment cost and human resources. Research on direct outcomes -- other-cause mortality, breast cancer mortality, radiation-induced cancer, and quality of life -- is not yet available, leading to uncertainty in the balance of health effects from using DBT in screening programs, the panel wrote.

"Although the [group] could not determine whether using DBT in addition to digital mammography in screening programs provided a net health benefit, it concluded that, overall, the undesirable consequences were greater than the desirable ones," the authors wrote.

The other recommendations (12-15) advise against tailored screening with automated and handheld breast ultrasound and MRI in certain situations, but support using DBT when suspicious lesions are detected at mammography screening.

How this relates to U.S. practice

Although the guidelines are coming from Europe, the challenges of supporting an informed screening decision remain the same, according to an accompanying editorial by Dr. Joann Elmore from the David Geffen School of Medicine and Dr. Christoph Lee from the University of Washington School of Medicine.

"Whereas the authors of the European Breast Guidelines address the diversity among European countries, more than an ocean separates the United States from Europe with regard to screening policies and practices," Elmore and Lee wrote.

Some of the differences include the health systems (single payor in Europe) and the fact that most European countries double read while the U.S. does not. Double reading may be feasible in the U.S. if performed by subspecialty-trained breast radiologists using teleradiology capabilities, or with emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technology used for the second reading. Double reading is also likely the reason the multidisciplinary panel recommends screening biennially or triennially, according to Elmore and Lee.

Another difference is the use of DBT for routine screening: Nearly two-thirds of U.S. facilities certified by the Mammography Quality Standards Act now have DBT units, and it's quickly becoming the screening method of choice.

"Reverting to 2D mammography screening while reserving DBT for only diagnostic imaging would be an unrealistic practice change in the United States, as well as in some European countries that have already adopted nationwide DBT screening," they wrote.

Mostly what the European Breast Guidelines highlight is a need for uniformity in the U.S. regarding the quality and outcomes of the diagnostic imaging workup after an abnormal screening result. Unlike the European group, U.S. policymakers stop their recommendations at the screening stage, thus creating wide variation in what happens after a screening abnormality is found.

"These new guidelines probably will do little to settle the ongoing debate in the United States over when to start mammography screening, what imaging method to use, and how often to screen," the authors wrote. "However, the European Breast Guidelines do provide insights into how we can use the knowledge gained from organized screening to identify areas and avenues for improving the quality and accuracy of breast cancer screening in the United States."