Masses in the liver often are difficult to diagnose and manage in adults, but they pose extra challenges in children, and radiologists must be resourceful and imaginative when using the various techniques for their workup, delegates heard at the recent Journées Francophones de Radiologie Diagnostique & Interventionnelle (JFR 2018).

Dr. Stéphanie Franchi-Abella, head of pediatric interventional radiology at Bicêtre hospital, in Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, illustrated the latest thinking on how to deal with liver tumors in children in terms of both diagnosis and management.

While the development of hepatocellular carcinoma as a result of liver disease in adults is well-documented in the literature, the field of liver tumors is far less known in children.

"If you find a liver mass in a child or a teenager please bear in mind there is a high probability of an underlying disease or malformation," noted Franchi-Abella in an interview with AuntMinnieEurope.com.

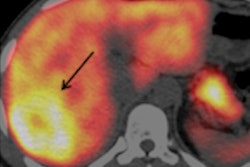

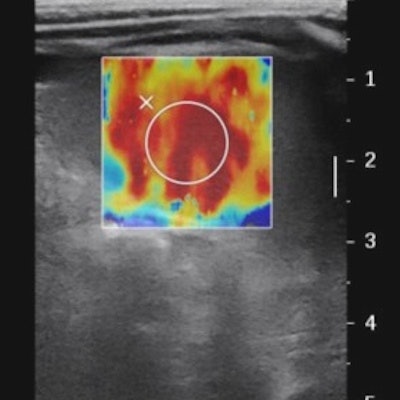

Multiparametric ultrasound exam in an 8-month-old baby referred for hepatoblastoma: Above: B-mode examination shows a heterogeneous liver with a well-circumscribed homogeneous tissular mass suspected in the initial center to be a nodule of hepatoblastoma. Below: Color-Doppler shows no specific vascularization of the mass. All images courtesy of Dr. Stéphanie Franchi-Abella.

Multiparametric ultrasound exam in an 8-month-old baby referred for hepatoblastoma: Above: B-mode examination shows a heterogeneous liver with a well-circumscribed homogeneous tissular mass suspected in the initial center to be a nodule of hepatoblastoma. Below: Color-Doppler shows no specific vascularization of the mass. All images courtesy of Dr. Stéphanie Franchi-Abella.In adults, a tumor may be discovered in follow-up of known cirrhosis or liver disease. In children, however, the tumor itself is often the first pathology that is discovered, usually with ultrasound, but this may be a lesion related to other diagnoses. Finding the underlying causes favoring the development of pediatric liver tumors remains one of Franchi-Abella's personal crusades, and the role of ultrasound should not be underestimated, she noted.

Furthermore, because similar tumor types may have different causes and implications for patients of different ages, their treatment varies: Doctors may manage a large hepatocellular carcinoma in an adult with transarterial chemoembolization, while a child or teenager may be offered surgery or transplant.

"Tumors may develop due to an underlying malformation or disease, and finding this is crucial to appropriate management. This means that radiologists need to look beyond the mass in the liver to the nontumoral liver and parenchyma to find other signs that yield information about a vascular malformation or a metabolic disease, for example. This will help define treatment, and the possibility of interventional procedures," Franchi-Abella noted.

She highlighted several cases, notably the congenital portal systemic shunt malformation that wholly depends on radiological diagnosis because there are no blood tests or clinical signs that can aid in diagnosis.

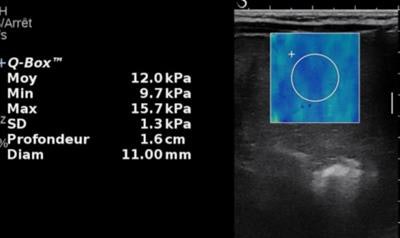

Same patient. Above: Elasticity of the mass is moderately increased (12 kPa). Second image: Elasticity of the liver parenchyma away from the mass is markedly increased (22.5 kPa). Last image: There is also a marked increase of spleen elasticity. In conclusion, the association of stiff liver and spleen is highly suggestive of chronic liver disease with a large regenerative nodule. This was confirmed by biology, which revealed tyrosinemia.

Same patient. Above: Elasticity of the mass is moderately increased (12 kPa). Second image: Elasticity of the liver parenchyma away from the mass is markedly increased (22.5 kPa). Last image: There is also a marked increase of spleen elasticity. In conclusion, the association of stiff liver and spleen is highly suggestive of chronic liver disease with a large regenerative nodule. This was confirmed by biology, which revealed tyrosinemia.Because radiologists are too focused on the lesion, they might sometimes overlook this vascular malformation, potentially the cause of the tumor, and often its solution.

"If the tumor is benign, we can close the malformation, and this intervention will help resolve the tumor and prevent future recurrence of others. If the tumor is malignant, we can resect the nodule, close the malformation, and often prevent recurrence in these cases, also," she noted, adding that liver transplantation may be necessary in exceptional cases.

Franchi-Abella and her department first published their findings about the technique in 2011. Since then, it has become routine practice for workup of this type of malformation with associated tumors.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is another type of metabolic disease in children that the radiologist should watch out for, she continued. With the rise in pediatric obesity, young patients are developing fatty liver diseases such as the more extreme NASH that may lead to hepatocellular carcinoma. This relatively new disease in Europe and the U.S. in children is increasing, and ultrasound plays a vital role in depicting its early signs: a large liver with hyperechoic fat deposits.

Other ultrasound signs of chronic liver disease that may reflect various etiologies are regular or irregular liver margins, a heterogeneous aspect of the parenchyma, nodular transformation, portal hypertension with enlarged spleen, and acquired porto-systemic shunts.

Dr. Stéphanie Franchi-Abella.

Dr. Stéphanie Franchi-Abella.Franchi-Abella was also keen to urge radiologists to look for abnormalities in the other abdominal organs. This key information will change diagnosis and/or management of the liver mass. For example, nephromegaly with hyperechoic renal parenchyma may reveal tyrosenemia, a metabolic disease, she noted.

For children, multiparametric liver ultrasound to show tumoral and nontumoral liver is the first line of deeper investigation, after the initial diagnosis of a liver mass. Different techniques should be used including grayscale, Doppler, elastography for fibrosis, Micro-Doppler to discern the vascularization of the tumor, and contrast-enhanced ultrasound to assess tumor behavior, and differentiate between malignant and benign lesions.

When optimal mutiparametric information has been gained from ultrasound, the pediatric patient might then undergo MRI and CT. Franchi-Abella noted that often in adult patients, doctors may discover a tumor through ultrasound, and will quickly pass to MRI and CT, only to return to ultrasound exams to get additional information that the other two modalities didn't provide.