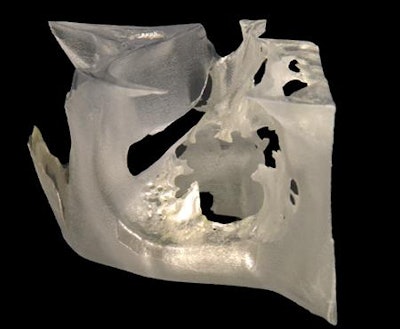

Swiss researchers have created patient-specific 3D-printed surgical guides to enhance the visualization of craniomaxillofacial fractures. Planning facial reconstruction using these 3D-printed models led to significant reductions in operating time and costs.

The group, led by Dr. Florian Thieringer and Dr. Philipp Brantner from University Hospital Basel, was able to make surgical guides for the repair of serious orbital floor and zygomaticomaxillary fractures at their institution's very own 3D printing lab. Using these models for preoperative planning and intraoperative guidance allowed surgeons to lower surgery times by an average of 33%, compared with conventional methods.

3D-printed anatomical guide for craniomaxillofacial surgeries. All images courtesy of Stratasys.

3D-printed anatomical guide for craniomaxillofacial surgeries. All images courtesy of Stratasys."Having access to on-demand 3D printing has revolutionized the way we work, most notably for craniomaxillofacial injuries," Thieringer told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "Not only do we save ourselves time, we gain security in the clinical process and improve the results in the treatment of our patients."

3D-printed surgical guide

Recent studies have shown that incorporating 3D-printed models into presurgical planning can reduce surgery times and lower costs. These benefits, in turn, could minimize the risk of postoperative complications and improve patient outcomes.

Applying this concept to craniomaxillofacial cases, Thieringer and colleagues produced 3D-printed models based on the CT scans of patients with complex fractures. Specialists at their hospital's in-house 3D printing lab accessed the medical images wirelessly using a virtual machine and converted them into virtual 3D models using segmentation software (Mimics Innovation Suite, Materialise).

Next, they printed relevant anatomical structures from the virtual models -- such as the orbital wall for cases requiring orbital floor reconstruction, for example -- using a 3D printer (Objet30 Prime, Stratasys) and biocompatible material (Med610). The 3D printing team completed preprocessing in approximately 15 to 20 minutes, the actual 3D printing in 1.5 to two hours, and postprocessing in 10 minutes.

Patient-specific 3D-printed model allows for the presurgical preparation of hybrid titanium mesh implants for orbital floor reconstruction.

Patient-specific 3D-printed model allows for the presurgical preparation of hybrid titanium mesh implants for orbital floor reconstruction.The resulting patient-specific 3D-printed models allowed clinicians to plan intricate procedures, such as orbital floor fracture repair, that tend to involve difficult-to-visualize injuries. What's more, the surgeons were able to refer to these patient-specific anatomical guides during surgery -- saving them a lot of time.

In addition to improving visualization, the 3D-printed models enabled the surgical team to form titanium meshes onto the 3D-printed models during planning, as opposed to the standard method of cutting and forming the meshes during the operation. These hybrid 3D-printed, titanium implants additionally removed the need to source titanium implants from external suppliers, Thieringer noted.

"Although forming titanium mesh implants before surgery is not new per se, what is innovative is the integration of the entire process into clinical routine by the 3D Print Lab at University Hospital Basel," he said. "This allows for the immediate availability of biocompatible models and guides, often even before the patient has seen the anesthesiologist for the preoperative medical consultation."

3D printing saves time, costs

In a preliminary study including 20 craniomaxillofacial cases, the researchers found that surgeons who used the hybrid 3D-printed model and titanium implant for preoperative planning and surgical guidance were able to complete surgery in roughly one hour, compared with 1.5 hours for the conventional method.

At an estimated cost of 70 Swiss francs (62 euros) per minute, decreasing the surgical time for these procedures by 30 minutes could potentially lead to savings of roughly 2,000 francs (1,772 euros) per operation.

Surgeons have also achieved similar reductions in surgery time when using 3D-printed implants produced by third-party manufacturers. However, outsourced 3D-printed implants generally come at a much higher price than the hybrid implants made with the group's in-house 3D printing technique.

Furthermore, based on clinical experience, it can be said the anatomical reconstruction of orbital defects with hybrid 3D-printed, titanium implants is more reliable and accurate than standard methods, Thieringer said. This shows that having an in-house 3D printing lab can ultimately benefit healthcare institutions, despite its high initial cost.

"In-house 3D medical printing has enormous potential for the individual treatment of patients, whether for surgery, internal medicine, or other disciplines," Thieringer said. "If a comparatively limited indication can already lead to considerable savings in time and quality improvements in the treatment of our patients, then I see many other opportunities where 3D printing may also be of enormous benefit."