Measuring 3D-printed knees may be just as effective as the standard technique of measuring multiplanar reconstruction knee MRI scans in determining ideal graft length for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, new research from Italy has found.

The group from the University of Turin created 3D-printed models based on the MRI scans of individuals with intact ACLs. They found the suggested graft length from the 3D-printed knee was nearly the same as the length determined by examining multiplanar reconstruction MRI scans.

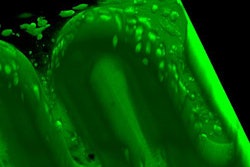

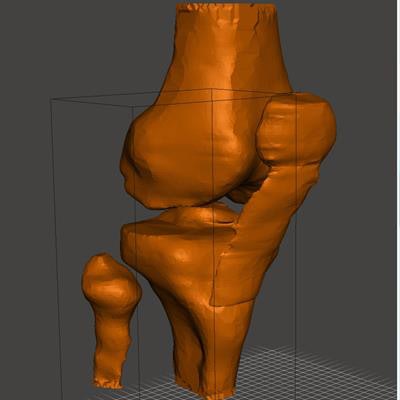

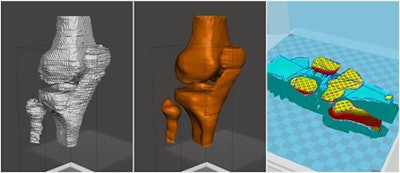

From left to right: Rough and smooth stereolithography models. Preview of temporary printing supports and printing parameters (layer height 0.2 mm, shell thickness 1.2 mm, bottom/top thickness 1.2 mm, fill density 5%). All images courtesy of Dr. Luca Jacopo Pavan.

From left to right: Rough and smooth stereolithography models. Preview of temporary printing supports and printing parameters (layer height 0.2 mm, shell thickness 1.2 mm, bottom/top thickness 1.2 mm, fill density 5%). All images courtesy of Dr. Luca Jacopo Pavan.The comparable measurements from both modalities makes 3D printing a potential alternative for presurgical planning and even simulation of ACL surgery, presenter Dr. Luca Jacopo Pavan told attendees at ECR 2018 in Vienna.

"3D printing is very useful for orthopedics because it can [enable surgeons to] simulate surgery before the intervention," he said. "It can also allow the orthopedic surgeon to try new tunnels on the [3D-printed] model and so see if there are some incompatibilities with a previous abrasion."

Reliable, cost-effective technique

Rates of ACL reconstruction procedures have been steadily rising in the past 20 years, noted Pavan, from the Institute of Radiology, Department of Surgical Sciences at the University of Turin. Preoperative planning for the surgery involves obtaining patient-specific measurements of the transepicondylar femoral axis -- roughly the width of the knee bone -- in order to determine the appropriate graft length required for reconstruction.

The most widely used method for collecting these data is to measure the knee on multiplanar reconstruction MRI scans using a caliper.

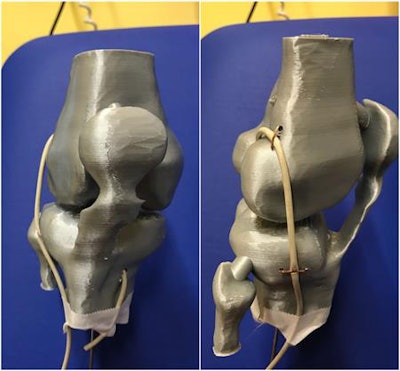

Frontal and lateral views of knee-printed model, with plastic cable positioned as a graft simulator according to Marcacci technique.

Frontal and lateral views of knee-printed model, with plastic cable positioned as a graft simulator according to Marcacci technique.Aiming to assess the viability of determining graft length using 3D-printed knee models instead, Pavan and colleagues collected T1-weighted images of the knee of 16 volunteers acquired with a 1.5-tesla MRI machine (Achieva 2.6, Philips Healthcare). There were six female and 10 male participants; their average age was 27, and they all had healthy ACLs.

Next, the researchers used several open-source, image-processing software (Osirix; Meshmixer; Cura; Slic3r) to segment and edit the MRI scans and finally create a 3D virtual model. After smoothing the virtual model and converting the file into stereolithography (STL) format, they 3D printed it with a 3D printer (Ultimaker 2+, Ultimaker) and polylactic acid material.

An orthopedic surgeon measured the transepicondylar femoral axis and calculated the graft length on the resulting 3D-printed models using a plastic cable as a graft simulator. A separate orthopedic surgeon and radiologist performed the same measurements on corresponding multiplanar reconstruction MRI scans.

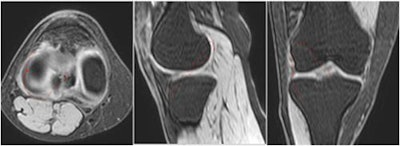

Measurements of graft length on multiplanar reconstruction images (from left to right: axial, sagittal, and coronal planes).

Measurements of graft length on multiplanar reconstruction images (from left to right: axial, sagittal, and coronal planes).The average time it took to process the MRI scans to create the 3D virtual model was 41 minutes and the average time to print the 3D-printed knee was 11 hours. The cost of the materials used to make each model was approximately four euros.

Jury is still out

Comparing the measurements of the two techniques, the researchers found the mean values of the transepicondylar femoral axis obtained on the 3D-printed knees and 3D multiplanar reconstruction MRI scans had a difference of less than a single millimeter. But the average calculated graft length on the 3D-printed model was 9.5 mm smaller than the graft on the reconstructed MRI scans.

| MRI versus 3D printing for planning ACL reconstruction | |||

| Multiplanar reconstruction MRI | 3D-printed knee | P-value | |

| Transepicondylar femoral axis | 83.1 mm | 82.2 mm | 0.056 |

| Graft length | 146.1 mm | 136.6 mm | < 0.001 |

Although the graft lengths calculated from the two different modalities were different to a statistically significant degree, the difference was still small enough to be "acceptable" from an orthopedic standpoint. This difference was most likely due to measuring vascular connective tissue around the knee joint on the multiplanar reconstruction MRI scans, but not on the 3D-printed model, Pavan said.

The authors acknowledged the study was limited by its small population size and the need to test the new measuring technique in real clinical scenarios. In addition, the lack of a reference standard for ACL reconstruction limits the use of 3D-printed knees to particular methods of ACL repair.

In the case of this study, Pavan and colleagues demonstrated the potential viability of measuring the transepicondylar femoral axis and determining the ideal graft length for repairing the ACL exclusively with the Marcacci reconstruction technique, which involves attaching to the knee an autograft harvested from the patient's hamstring. However, many medical centers have since replaced this traditional transtibial method with newer ones such as anteromedial portal or all-inside ACL reconstruction, Dr. Anagha Parkar, staff radiologist at Haraldsplass Diakonale Sykehus in Bergen, Norway, told AuntMinnieEurope.com in response to this study.

"Currently, I would say presurgical planning with 3D printing could be useful only for measuring hamstring graft length," said Parkar, who is a member of the editorial advisory board of AuntMinnieEurope.com. "But there are controversies on whether a bone patellar tendon, quadriceps, or hamstring graft is best for ACL reconstruction ... [and] the jury is still out on which technique is best in the long term."

For now, one of the benefits of using 3D printing may be examining the healthy knee in order to plan procedures for the injured knee, but this would require further clinical studies comparing knees, she added.