MRI results have revealed that even moderate drinking is linked to declines in brain health. The results of the 30-year study have important public health implications because alcohol consumption affects such a large percentage of the population, concludes a new study in BMJ.

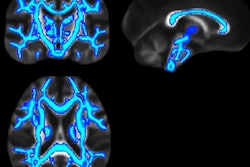

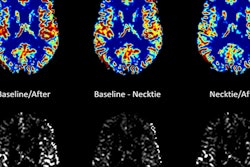

Researchers from the University of Oxford and University College London aimed to investigate the effects, if any, of moderate drinking on brain structure and function, as assessed by cognitive tests and a single MRI scan at the end of the study of 550 individuals. Higher alcohol consumption was associated with an increased risk of hippocampal atrophy, affecting both memory and spatial navigation. Even light drinking versus abstinence had no protective effect on brain health.

"Alcohol might represent a modifiable risk factor for cognitive impairment, and primary prevention interventions targeted to later life could be too late," noted Anya Topiwala, a clinical lecturer from the University of Oxford, and colleagues (BMJ, 7 June 2017).

Heavy drinking is known to be associated with poor brain health, but few studies have studied the effects of moderate drinking on the brain -- and those studies have shown inconsistent results, they wrote.

The investigators used data on weekly alcohol intake and cognitive performance measured repeatedly between 1985 and 2015 in 550 healthy men and women (mean age 43 at the start of the study) who were participating in the Whitehall II study. They performed brain function tests at regular intervals, following by an MRI scan.

After adjusting for several confounding factors, the group found that higher alcohol consumption over the 30 years of the study was associated with increased risk of hippocampal atrophy. Participants consuming more than 30 alcohol units per week were at the highest risk compared with nondrinkers, but even moderate drinkers (14 to 21 units per week) were three times more likely to have hippocampal atrophy compared with abstainers. Even light drinking of seven or fewer units a week had no protective effect over total abstinence, they wrote.

Higher alcohol consumption was also associated with poorer white matter integrity, which is crucial for efficient cognitive functioning, and faster decline in language fluency, measured as how many words beginning with a specific letter can be generated in one minute.

"Our findings support the recent reduction in U.K. safe limits and call into question the current U.S. guidelines, which suggest that up to 24.5 units a week is safe for men, as we found increased odds of hippocampal atrophy at just 14 to 21 units a week, and we found no support for a protective effect of light consumption on brain structure," the group reported.

In an editorial accompanying the study, neuropsychiatrist Killian Welch wrote that the findings strengthen the argument that drinking habits many regard as normal have adverse consequences for health.

"We all use rationalizations to justify persistence with behaviors not in our long-term interest," Welch added. "With publication of this paper, justification of 'moderate' drinking on the grounds of brain health becomes a little harder."