CHICAGO - The mummified hearts of upper crust French folk who lived 400 years ago reveal that atherosclerosis was a prevalent disease -- at least among the well-to-do, according to a study presented this week at RSNA 2015.

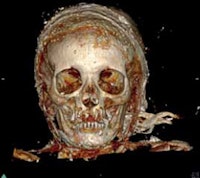

A 3D reconstruction with volume rendering of the head, frontal view. All images courtesy of Journées Françaises de Radiologie (JFR).

A 3D reconstruction with volume rendering of the head, frontal view. All images courtesy of Journées Françaises de Radiologie (JFR).Imaging the hearts with CT and MRI was possible because of a custom among the wealthy to have the heart removed from the body. It was then enclosed in a heart-shaped lead urn that was hermetically sealed, said Dr. Fatima-Zohra Mokrane, a radiologist at Rangueil Hospital, University of Toulouse.

The archeological team unearthed some 800 human remains that were buried at the Convent of the Jacobins in Rennes, France. Among the bodies, the excavators found five of the heart-shaped urns, some of which had inscriptions that made identification of the body possible. One such urn contained the heart of Louise de Quengo, Lady of Brefeillac, a well-known personality of the times, Mokrane said at a press conference.

"We tried to see if we could get health information from the hearts in their embalmed state, but the embalming material made it difficult," she said. "We needed to take necessary precautions to conduct the research carefully in order to get all possible information."

The urns were taken to Toulouse where they were carefully opened and then scanned. One heart was not well-preserved and yielded no useful information. Three of the other hearts were examined, and the researchers found evidence of atherosclerosis.

Mokrane said the findings could be declared proof that atherosclerosis occurred in these patients because the tissues were well-enough preserved. Another heart showed evidence of wall thickening, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Two hearts had dilated cardiomyopathy, indicating a possible cause of death, she said. One heart was normal.

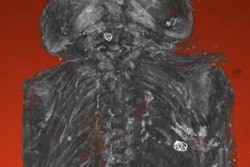

A 3D reconstruction with volume rendering of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, frontal view.

A 3D reconstruction with volume rendering of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, frontal view.The research team carefully cleaned the hearts, removing the embalming material, and MRI and CT scans were redone. On the new set of CT images, the researchers were able to identify the different heart structures, such as chambers, valves, and coronary arteries. Once the tissue was rehydrated, they were better able to identify myocardial muscles with MRI. Classic techniques, such as dissection, external study, and histology, were also used to examine the heart tissues.

The heart and remains of de Quengo were reburied by relatives. The other remains are being returned to families if they can be identified after pertinent research is completed, Mokrane said. The researchers encountered no objections from religious organizations in performing the research, she noted.

"Atherosclerosis is an ancient disease, although uncommon 400 years ago," said press conference moderator Dr. Salomao Faintuch, an assistant professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School. "Most of the people had poor living conditions and did not live long, usually dying of infectious diseases. But the rich lived to older ages. They had access to plenty of food and fat, and they got atherosclerosis in the same way that people do today."