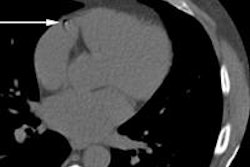

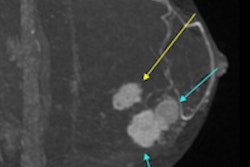

One of the popular innovations that has accompanied the newer generations of CT scans is the capability to place electronic arrows highlighting foci of interest. To the untrained eye, those bright, clearly observable markers bring into clarity densities and lucencies not always so readily observable. Yet, in an instant with an arrow they are better appreciated. The arrow points out the hitherto obscured lesion for everyone to see, no doubt about it, or well, maybe it does.

As the old saying proclaims, a picture is worth a thousand words. The affixed arrow is an unspoken directional signal inserted so the suspected abnormality, however subtle, will not get lost within a background of black, gray, and white where otherwise it might be unidentifiable until the arrow exposes it.

Dr. Stephen Baker, professor of radiology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, New Jersey, U.S.

Dr. Stephen Baker, professor of radiology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, New Jersey, U.S.Ask many referrers and they are apt to say the electronic arrow is a valued technological advancement which makes a seemingly unperceived pathological entity immediately recognizable. The placement of the arrow brings out the presence of pathology. So why be critical of it? Isn't it mere crotchety pedanticism to offer such a complaint? Maybe, but allow us, then, to present our arguments for the retirement of the electronic arrow from our diagnostic armamentarium. Each point we wish to make we feel strongly about. We hope at least one of them has resonance with you.

First, there is the aesthetic issue, if you will. We as radiologists cannot depict the physical reality of what is within the body. We only discern a simulacrum of it. We know there are some things not starkly depicted by the image but which are present nonetheless. Also, we can recognize anatomy and pathology by the pattern produced by how the x-ray beam passes through or is blocked. Into these pictures we then intentionally place a foreign "object," more opaque than bone, and homogeneously dense. Actually it is not even a physical object but a virtual one sharply defined and bright.

The arrow in its directing function overwhelms the image to the extent that other things not singled out may not be recognized by the viewer, whether he or she is a radiologist or a referrer. Such subtleties not indicated by the arrow are a setup for the avoidable satisfaction of search error. And multiple arrows even more so induce not only an aesthetic disturbance to the image, but also enhance the likelihood that a significant but inherently less obvious finding will become even less obvious, but no less significant, if situated beyond the environs of the intrusive arrow.

Yes, a picture is worth a thousand words, but what are our words worth? If we characterize a spot on the image solely or predominantly by its adjacency to an extracorporeal arrow, have we fulfilled our function as image interpreters or are we merely signpost inserters? Arrows indicate purported presence but our mission is greater than that. We are obligated to give an account of, for each density or lucency, its borders, configuration, internal architecture, location, and if it is part of a series, a comparison with previous images to determine growth or regression.

Thus an arrow alone is insufficient whereas a clear explanation in a narrative encompassing each of those features is sufficient. And thus the arrow is then really unnecessary, superfluous to the provision of a verbal or written delineation of the radiographic characteristics of the abnormality.

Hence, by relying on an arrow alone as a manifestation of our special capabilities, we do not provide all of the pertinent information required of our expertise. Furthermore, let us not forget that the arrow can be removed leaving the clinician with nothing if we don't also relate what we observe and report it in a comprehensive manner.

Dr. Johan Blickman, editor in chief of the European Journal of Radiology.

Dr. Johan Blickman, editor in chief of the European Journal of Radiology.But the most cogent reason for suggesting that such arrows should be relegated to residence in an electronic time capsule speaks to what are the lineaments of a radiologist's responsibility in 2015 and beyond. How many editorials have you heard or read about the duty of a radiologist to recast or at least augment his or her participation in care-rendering, not merely as an image reviewer but as a readily accessible collaborator in the diagnostic process?

We are guilty of often dispersing this message, as are an expanding chorus of sermonizers. But we strongly believe, for the sake of the vitality of our specialty, that we are on the right path! Such a prescription for a closer connection to our clinical colleagues is apt. Its realization is crucial for our survival in a competitive environment in which many in other specialties can and might wish to take a piece of the imaging pie we now control.

If we cannot give them what we should offer, i.e., a prompt, germane, detailed report provided often within the context of an accompanying dialog with our referrers in which understanding is gained without the need for surrogate markers, than ultimately our authority is endangered. In this strategic formulation electronic arrows are merely a figurative crutch we can very well do without. We need to be informative and participatory as caregivers, alerting our colleagues with more incisiveness and counsel than an arrow alone enables.

Hence, if we accept the fact that, be it critical or incidental, it is better for all concerned to describe a finding than to merely point it out, then we should break the arrows habit by going "cold turkey." Once you get over its removal, and start to describe everything you see, you will soon feel no remorse for the arrow's departure.

So are arrows more "value added" or not? You decide.

Editor's note: This article was published online by the European Journal of Radiology (EJR) on 20 August 2015. We have reproduced it with the authors' permission.

Dr. Stephen Baker is professor of radiology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, N.J., U.S., and Dr. Johan Blickman is professor and vice chairman at the Department of Imaging Sciences, University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, N.Y., and editor in chief of the EJR.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.