Imaging studies have confirmed that meditation can create the same physiological changes in the brain as medication for patients with clinical depression. More research needs to be done, but initial evidence suggests that, instead of medicating, people should try meditating.

Meditation rivals medication for patients with clinical depression, imaging studies show.

Meditation rivals medication for patients with clinical depression, imaging studies show.In a new assessment that included 51 studies, 12 of which examined structural and functional changes in the brain, researchers found an increase in gray-matter volume and density in those who meditate -- the same changes experienced by patients who take medication. In particular, they discovered changes in the prefrontal cortex, right amygdala, and hippocampus (Radiography, 22 August 2015).

"Although this wasn't a primary research project, it was clear from the systematic review process that there is a growing evidence base supporting meditation in place of medication," noted senior study author Pete Bridge in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com. Bridge, directorate of medical imaging and radiotherapy at the University of Liverpool School of Health Sciences in the U.K., conducted the study along with undergraduates Soraya Annells and Kristina Kho while he was the course coordinator for the radiation therapy degree program at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia.

Depression, medication, and meditation

In 2008, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that depression affected 1 million Australians and further stated that 1 in 7 people will have depression at some point in their life. Evidence links depression with changes in the levels or activity of certain chemicals or areas in the brain. In particular, a reduction of available monoamine neurotransmitters, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, induces depression. Clinicians have prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to aid patients.

However, medication comes with side effects, and patients must continue taking it to avoid relapse. Is there an alternative? The answer seems to be "yes," particularly when neuroimaging technologies such as structural MRI and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), as well as functional MRI (fMRI), PET, and SPECT, allow for investigation within the brain. Now, the biology and neuroscience of meditation may be measured, and researchers are finding meditation does the same thing as medication.

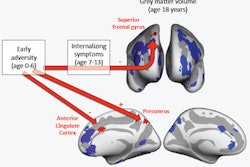

Prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for executive cognitive function, and as part of this it moderates the activity of the amygdala. When the prefrontal cortex is dysfunctional and the normal suppressive activity is absent or reduced, the amygdala becomes hyperactive, leading to depressive symptoms, according to Bridge, who is working on his doctorate, and colleagues. Antidepressants imitate the prefrontal cortex function and suppress an overactive amygdala.

Kristina Kho and Soraya Annells present at their first conference.

Kristina Kho and Soraya Annells present at their first conference.A study in 2005 used MRI to compare cortical thickness between meditators and a randomly selected and matched cohort of nonmeditators. When the images of the two groups were compared, researchers found particular areas of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, in long-term meditators were thicker than in nonmeditators.

Functional imaging studies using PET, SPECT, and fMRI confirm this increase of cortical thickness is consistent with repeat activations of these structures, Bridge's team wrote. Several functional studies further demonstrated functional activations of the prefrontal cortex, right insula, or left temporal gyrus, which is consistent with suggestions that meditation could promote neural plasticity in regions that are routinely engaged during the meditative practice.

Right amygdala

Another area of the brain that's affected in patients with depression is the amygdala, which is inhibited along with other limbic regions. In 2012, one study monitored longitudinal effects of meditation on the amygdala by using fMRI on participants while they were presented with photographs of people in various settings. The photographs were designed to elicit a range of positive, negative, and neutral emotional responses from the participants, according to the researchers.

The fMR images were taken three weeks before the eight-week mindfulness program commenced and again three weeks after the intervention. Meditators and nonmeditators did not show any significant difference before the intervention. The researchers found that mindfulness training reduced right amygdala response to emotional stimuli even while participants were not meditating, indicating a change in brain function in a nonmeditative state.

"This suggests that meditation can improve emotional stability and response to stress with enduring beneficial changes in brain function, in particular those areas concerned with emotional processing," Bridge and colleagues wrote.

Another study found a significant statistical decrease in right amygdala gray matter density (p = 0.042) after meditating.

Hippocampus

Studies have linked hippocampal volume loss with depression through MRI. Alterations of neural networks involving the hippocampus have been associated with impaired emotional processes, memory, and executive functions in major depression.

An MRI study in 2009 compared 22 long-term practitioners of different meditation traditions with a control group of 22 people who were matched for gender age and duration of education. Their results were consistent with the findings of an earlier matched comparison study on the effects of mindfulness meditation on brain structure.

A region of interest (ROI) analysis demonstrated statistically significant increases in density of the right hippocampus (p = 0.027) and right insula (p = 0.022) when comparing meditators with nonmeditators.

The same researchers conducted a follow-up study in 2011 and found an increase in gray matter of the hippocampus, which confirmed the results of another study demonstrating an increased size, thickness, and density of gray matter in the left hippocampus and left inferior temporal lobe after meditating. The changes were similar to those seen following the administration of an antidepressant for treating depression.

Keep going

The literature review confirms the resulting decreased gray matter of the amygdala and increased gray matter of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex can counteract the dysfunction of these structures in depressed patients.

Future medical imaging studies should include larger sample sizes, longitudinal studies, and limit the form of meditation practice undertaken by the sample -- in this review, the types of meditation varied across the studies, but the results were consistent regardless of type.

"We do hope that the paper helps to grow the evidence base for meditation and perhaps leads to more rigorous follow-up clinical trials as suggested in the paper," Bridge wrote.