When radiologists talk about "beautiful images," they mean clear and accurate visualizations showing unmistakable signs of disease and injury, but the main goal of photographic artist Nick Veasey is to use x-ray to reveal the invisible. His new exhibition in Geneva runs until mid-October.

He discovered the medium of radiography as a young advertising and design professional, when he x-rayed a soda can for a TV show. After this initial encounter, he was inspired to image other objects, starting with his own shoes. Over the years, his subjects have ranged from feathers, frogs, and flowers to TV sets, motorbikes, passenger buses, and even a Boeing 777.

In the work "Superman and Clark Kent," the bones of the human character are visible through the outer trappings of his alter ego Superman, and the cloak and the "S" on the tunic are faintly depicted. All images courtesy of Nick Veasey, Radar Studio.

In the work "Superman and Clark Kent," the bones of the human character are visible through the outer trappings of his alter ego Superman, and the cloak and the "S" on the tunic are faintly depicted. All images courtesy of Nick Veasey, Radar Studio.The human form features heavily in many of his images. Although the depictions are posed life-like in stances such as riding motorbikes or crouching before a race, the subject is a skeleton previously used for training resident radiologists.

"I'd love to be able to image the human body, but it is not ethical," Veasey told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "I have worked in a variety of NDT (nondestructive testing) labs. In one lab, a mobile x-ray source was hotwired with the safety door left ajar. I walked past the door at the wrong time. This happened twice."

Veasey enjoys providing a unique view of everyday objects in use. The human element makes the pictures "come alive."

Veasey enjoys providing a unique view of everyday objects in use. The human element makes the pictures "come alive."Veasey's x-ray machine goes up to 200 kV and emits radiation for sometimes as long as 20 minutes, depending on the density of the object and the desired visual effect. The potentially lethal level of x-ray radiation and emission times make his work extremely hazardous.

To avoid radiation-related accidents, his lab, Radar Studio, is in the middle of an isolated field in Kent, England. The building itself is a Cold War era spying station purchased from the military. It has been refurbished to make it safe for those working inside it -- or anyone in the vicinity. The studio is constructed of 10 cm-thick blocks of lignacite that prevent x-rays from passing through the walls. The floor is made from a high-density concrete that absorbs radiation, while the lead and steel door to enter the x-raying area weighs 1,250 kg.

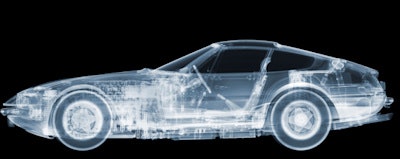

The Ferrari Daytona grand tourer automobile was produced from 1968 to 1973, and was a traditional front-engined, rear-drive car.

The Ferrari Daytona grand tourer automobile was produced from 1968 to 1973, and was a traditional front-engined, rear-drive car.Veasey wears no further protective clothing, relying on the shielding to protect him. He used to wear lead underpants, but stopped for "reasons of personal comfort." The artist previously used a 1970s Philips source, but now works with a COMET source and analogue film. Every image taken is to scale and captured on 35 cm by 43 cm sections. This is more than enough room if he is x-raying a dandelion or a mobile phone, but for larger objects such as motorbikes and cars, it means dismantling the whole vehicle and x-raying every single component individually.

Veasey eventually turns all the x-rays into digital files by scanning them on a 1980s drum scanner. The files are then imported to a computer and "sewn" together digitally with the visible overlap of the numerous x-ray sections removed.

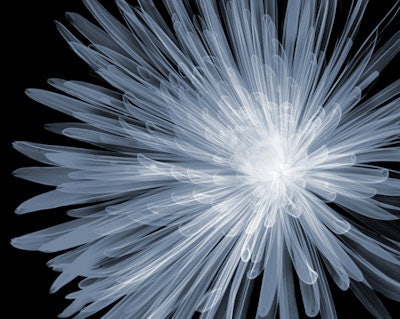

Getting the scan settings right is particularly important for delicate objects such as plants.

Getting the scan settings right is particularly important for delicate objects such as plants."I'd really like access to these full body x-ray machines I have heard about," Veasey said, adding that he was also interested in the idea of sharing images or facilities with radiologists, if patient confidentiality could be protected.

Veasey's work transports the observer through the everyday to the fantastic: It shows familiar objects in a way they haven't been shown before from the mechanical or digital inner workings of computers, stereos, or car motors, to the biological structures of the natural world.

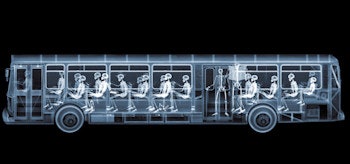

This image was created using the same skeleton, "Frieda," posed in different areas of a bus, which was imaged in sections with a cargo scanner.

In the adjacent image, a ghostly bus reveals its passengers engaged in a variety of activities, such as listening to headphones or reading a magazine. Veasey explains that this scene was created with the same skeleton posed in different seats and a real bus imaged in sections, this time with a cargo scanner.

The artist is particularly proud of his plant exhibits. The delicate filigree of a flower's structure that allows its capillary action is not just fascinating to look at in x-ray, but pays homage to the natural world, as do honeycomb structures of modern architecture, he explained.

Nick Veasey considers himself "anti-fashion" because he doesn't show the surface, just what is within. People all look the same inside, he said.

Nick Veasey considers himself "anti-fashion" because he doesn't show the surface, just what is within. People all look the same inside, he said.However, different exposures can drastically alter brightness and clarity, which means that choosing the right setting to capture a flower is a very subtle operation. Indeed, all his subjects require careful consideration to avoid over- or underexposure that would obscure important details.

"A feather I'd image for about three minutes and 20 seconds, with very low kV," Veasey said, adding that he would scan a TV set for two minutes.

In a society saturated by airbrushed and photoshopped pictures, the x-ray art would seem to point to the truth that lies beneath gleaming surfaces or perfect skin. His current projects include iconic classic cars, super luxury brands, and celebrity portraits animated through lenticular display.

"My art is immediate. You get it straight away. Yet upon detailed inspection, I reveal a lot of hidden detail and beauty," Veasey said. "It is a beautiful world out there, a beautiful life we are blessed with. Sometimes you have to look hard to find the beauty, but it is always there."

The exhibition is being held at the MB&F M.A.D.Gallery. For more details, click here.