LONDON - Find at least half of invasive breast cancers when they are smaller than 14 mm in size. That was the key message of the screening pioneer Dr. László Tabár, speaking at last week's special lecture event organized by the British Institute of Radiology (BIR).

"The rest is all hand-eye coordination -- establish the diagnosis, determine if the cancer is unifocal or multifocal, and provide all this information to other team members," said Hungarian-born Tabár, who is a professor of radiology at University of Uppsala School of Medicine in Sweden. "Treat the woman, but first of all steal time from cancer."

Pathologists contribute to the underdiagnosis of multifocal breast cancer cases, according to Dr. László Tabár.

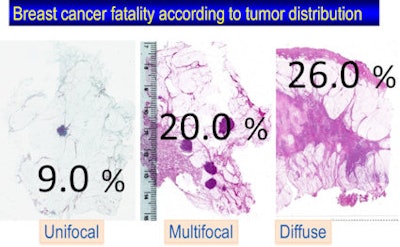

Pathologists contribute to the underdiagnosis of multifocal breast cancer cases, according to Dr. László Tabár.He spelled out the challenges that remain, despite the incredible advances since the early days of screening in the 1970s. Unifocal cancers, accounting for 40% of cases, should not kill anymore in the 21st century, he asserted.

"They are detectable at mammography screening and relatively easy to treat surgically using breast-conserving surgery," Tabár noted. "Multifocal breast cancers have a worse prognosis -- with twice the fatality as unifocal cancers -- partly because the tumor burden is higher, partly because they are often underdiagnosed and therefore undertreated."

He is convinced pathologists contribute to the underdiagnosis of multifocal breast cancer cases because they do not use large-section histology.

"Unfortunately, very few institutes use this technique, which should be compulsory in the modern era. Also, the current TNM [primary tumor, lymph nodes, metastasis] classification neither appreciates the term 'multifocal' nor the term 'diffuse' breast cancer, although most of the breast cancer deaths occur in these two subgroups," Tabár said.

He also drew attention to the value of a multimodal approach, including MRI, for preoperative workup of a case. If this is not done, then the real extent of the disease may not be known preoperatively and the outdated, small-section histology technique will not find all the cancer foci, which will continue growing, despite the use of adjuvant therapeutic regimens. This may result in tumor spread and jeopardize the patient's life, he explained.

Minimize advanced cancers and deaths

Detecting invasive cancers of up to 14 mm in size results in significantly fewer advanced breast cancers, Tabár said, adding that reducing the advanced cancer rate is the prerequisite for decreasing breast cancer deaths.

"There is a parallel between the incidence of advanced cancers and the breast cancer specific mortality rate in any given population, since most breast cancer deaths occur in women whose tumors were at an advanced stage at the time of detection," he pointed out, adding that analysis of the data from successful mammography screening programs supports this.

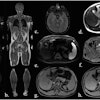

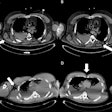

Two examples of nonpalpable, screen-detected unifocal breast cancer smaller than 10 mm. Images courtesy of Dr. László Tabár.

Two examples of nonpalpable, screen-detected unifocal breast cancer smaller than 10 mm. Images courtesy of Dr. László Tabár.Introducing Tabár at the BIR event, called "A new era in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer," Dr. Michael Michell, consultant radiologist at King's College Hospital National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust in London, explained that Tabár led the initial trials from the 1970s that looked at mammography screening and breast cancer, and all service screening programs are based on these trials.

After a brief overview of how little had happened in tackling breast cancer in the 5,000 years since a case was first recorded on an Egyptian papyrus until the 1970s, Tabár remarked that a major development was discovering the growth rate of breast cancers. This understanding was key to determining the interval for screening for the disease. He and his colleagues carried out extensive research on assessing the tumor growth rate according to patient age and histologic tumor type. This resulted in a recommendation for the length of the interscreening interval for women in different age groups.

"The optimum interval is between 12 and 18 months in women aged 40 to 54 years, and 18 and 24 months in women aged 55 to 74 years," he noted.

A major technical development in the mid-70s was the invention of low dose film-screen mammography that enabled detection of breast cancers in their nonpalpable phase. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) tested the hypothesis that detection of the disease in an earlier, nonpalpable phase results in a significant decrease in mortality from the disease.

"To date, we have eight population-based RCTs that have been published and reviewed," Tabár said. "There is unequivocal supporting evidence from prospective RCTs that an invitation to mammography screening is associated with a reduction in the risk of dying from breast cancer."

He explained that screening trials show the following:

- Early detection of breast cancer can prevent death from the disease.

- Breast cancer is not a systemic disease from the outset.

- Breast cancer is a progressive disease, whose progression can be halted by early detection and treatment.

- The decisive factor is whether the treatment is given early or late in the natural history of the disease, rather than which treatment choice is offered to patients.

- Both screening and improved treatment regimens contribute to the current decrease in mortality in breast cancer.

- High quality mammography screening can be considered a major public health achievement.

- Opponents of early detection through mammography screening aim to discredit the most important control mechanism for breast cancer deaths ever invented.

Benefit vs. harm

In response to being asked for his thoughts on the ongoing debate concerning the pros and cons of screening, Tabár said that despite the accumulated and overwhelming evidence in favor of screening, the alleged harms of mammography screening continue to be avidly discussed.

"The harm of not attending mammography screening has seldom been discussed in the medical literature -- until recently [Radiology, March 2012, Vol. 262:3, pp. 797-806]. But of all the harms associated with breast cancer screening, the greatest harm comes from nonattendance," he emphasized.

In no uncertain terms, he stressed the positives of mammography screening including fewer breast cancer deaths, significantly better disease-specific survival, and relapse-free survival and better overall survival. "There are also fewer mastectomies and a higher frequency of breast conserving surgery, as well as fewer patients needing more severe forms of adjuvant therapy."

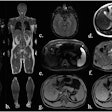

The fatality rate is 2.2 times higher in multifocal cases compared with unifocal breast cancer cases, and 2.9 times higher in women with diffuse breast cancer. Image courtesy of Dr. László Tabár.

The fatality rate is 2.2 times higher in multifocal cases compared with unifocal breast cancer cases, and 2.9 times higher in women with diffuse breast cancer. Image courtesy of Dr. László Tabár.For healthcare professionals and women concerned about journal articles and media reports that discuss the negatives of mammography screening, he pointed out that meticulous and credible reviews have been carried out by numerous independent expert panels in Europe and the U.S. and consistently reached the same conclusion: Early breast cancer detection and treatment results in decreased breast cancer mortality.

"Clinicians should have confidence in the current recommendations issued by leading organizations, and they should impart that confidence to their patients," remarked Tabár, adding that it would be wrong to use the Goetzsche error-prone analysis to discourage an early-detection procedure that has been shown in trial after trial to reduce breast cancer mortality (CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, March-April 2002, Vol. 52:2, pp. 68-71).

The analysis from Peter Goetzsche's of the Nordic Cochrane Center lacks access to individual patient data and fails to adhere to well-established evaluation methods, he argued. "These elementary limitations were immediately apparent to competent investigators, some of whom published rather harsh criticism," he said.