Both the lowly stress test and the coronary calcium scan can help triage stable patients with chest pain, often leading to successful conservative management that sidesteps coronary CT angiography (CCTA) entirely. In other scenarios, of course, CCTA is the first step that can help clinicians avoid further testing on the path to diagnosis, concludes a presentation at last month's International Symposium on Multidetector-Row CT.

It depends on the patient, said Dr. Koen Nieman, PhD from Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. And both the exercise treadmill and calcium scoring -- of late somewhat neglected tools to evaluate chest pain patients -- have important roles in their ability to avoid both invasive angiography and CCTA in patients who can be managed conservatively, he said. "In patients with a calcium score of zero, the number with obstructive coronary artery disease is very low ... This is something that we can exclude with a calcium score in about 40% of our patients."

At other times, coronary CCTA is indispensable for avoiding invasive and unnecessary interventions, handily distinguishing significant coronary blockages and excluding patients whose stenoses are unlikely to have an important clinical impact. Overall, CCTA is a great test for ruling out coronary artery disease in patients with a low or intermediate probability of coronary artery disease, with great sensitivity and negative predictive value, though it's somewhat less efficient for diagnosing high-probability patients, he said.

"But while we can exclude coronary artery disease it's much more difficult to accurately deal with positive findings, which is why the specificity and positive predictive value of coronary CT angiography are not perfect," Nieman said, adding that many studies and meta-analyses have born this out.

A key issue with CCTA is function versus anatomy, in that CCTA often finds anatomic stenosis that isn't always flow-limiting.

"And I think it's important to realize that there is a certain cascade in the phenomena that occur when ischemia increases as coronary artery narrowing increases that can be tested with several tests," he explained.

For example, SPECT is particularly sensitive for myocardial ischemia. Dobutamine stress echocardiography is a good way to detect motion abnormalities. ECG changes in chest pain are often caught on the exercise treadmill test, which offers high specificity even though sensitivity is low, he said. And CCTA can be very efficient even in chest pain patients who might even have had abnormal exercise stress test results, and conversely, the treadmill can play a role in determining the functional severity of stenosis diagnosed at CCTA, he said.

Because CT can show abnormalities when flow isn't limited, when looking for coronary artery disease and deciding on patient management it's important to combine both anatomical and functional information using one of several available tests, according to Nieman.

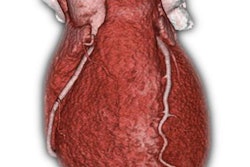

Significant coronary artery stenosis that isn't

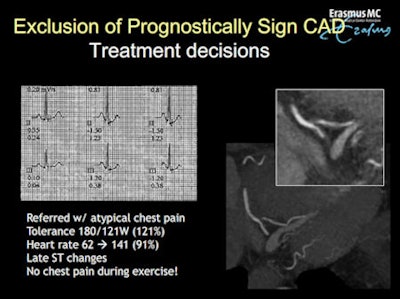

CT might even find a significant lesion causing the ischemia that is still not clinically important, he said. In his facility, for example, a 62-year-old man with a lesion in the posterior descending artery did a great job at the exercise test, performing above expectations. But ST depression at ECG manifested toward the end of the exercise. CCTA revealed that the stenosis involved prognostically irrelevant vessel, and therefore revascularization would yield no prognostic benefit, Nieman said.

A 62-year-old man presenting with stable chest pain showed significant stenosis at CCTA in the posterior descending artery, and was not revascularized. All images courtesy of Dr. Koen Nieman, Erasmus University Medical Center.

A 62-year-old man presenting with stable chest pain showed significant stenosis at CCTA in the posterior descending artery, and was not revascularized. All images courtesy of Dr. Koen Nieman, Erasmus University Medical Center."Even if we do find lesions that are stenotic and even if we can't rule out that these lesions are causing ischemia, what we do know is that revascularizing this patient will not improve his prognosis, and therefore what we can do is ... treat the patient with medication before we move on to an intervention," he said. "So I think the role of cardiac CT in this matter goes beyond the exclusion of coronary artery disease, it goes to the level of excluding prognositically important coronary artery disease, and I think that's what we're doing in practice with patients who do not have three-vessel disease, two-vessel disease in proximal vessels, or other important anatomic features."

Calcium as gatekeeper

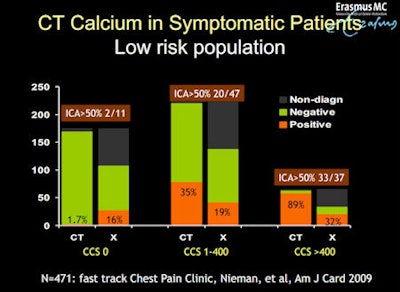

The CT calcium scan can reduce the need for CCTA in many patients, Nieman said, citing a study of 471 patients at his group's Fast Track Chest Pain Clinic. In patients with a calcium score of zero, just 1.7% had obstructive coronary artery disease, and all of them were single-vessel disease without prognostic consequences, he said.

A series of 471 low-risk chest pain patients with no calcium showed just 1.7% with significant disease.

A series of 471 low-risk chest pain patients with no calcium showed just 1.7% with significant disease."In this way, significant disease can be excluded in about 40% of the center's patients, and in fact we do not need to do a CT angiography," he said. Even in patients with very high calcium scores (more than 400), CCTA exams are often normal, often diminishing the value of the scans in this group, though there is uncertainty about setting the calcium threshold at 400.

"Some people will disagree with that," he said, notably Gottleib et al, who in 2010 found significant disease in patients with low calcium scores, but those patients were already at high risk of coronary artery disease and recruited after referral to the cath lab, he said. Moreover, the conclusions of Gottleib et al are contradicted by a much larger 2004 series by Knez et al, who confirmed a 99% sensitivity of calcium scoring for ruling out coronary artery disease in patients at high risk. This was also the case in the CONFIRM trial, which showed that patients without calcium or with very low scores had low rates of intervention. At Nieman's institution such low-risk patients are still catheterized, but not revascularized, he said.

CCTA then exercise?

Traditionally, chest pain patients were given a stress test or an exercise test, which, if nondiagnostic, resulted in a referral to CCTA, but different approaches are now possible, he said.

"I think that is changing over time, and I think there is an important role for the calcium scan to avoid invasive angiography," he said. "Cost is an important incentive, but also I think that radiation exposure and contrast exposure is important. In my opinion, the CT scan can be done first, we're actually testing that in a randomized controlled trial ... and then maybe the exercise test should be done after the [CT] angiogram to make sure the lesion that we're looking at is actually hemodynamically significant."

When and how the functional significance of a stenosis can be determined by a simple exercise test, or whether a more advanced test like CTA-based fractional flow reserve or SPECT myocardial perfusion test is needed, is a question that needs further validation, he said. In the meantime, "In our institution we often get away with an exercise test at this moment while we're testing these new fancy applications," Nieman said.