Abdominal radiologists must be familiar with fundamental staging points of pancreatic cancer and interpretation of imaging findings, leading to optimal patient management selection, a top research group from Amsterdam has emphasized.

Multidetector-row CT (MDCT) is the mainstay and workhorse for pancreatic cancer staging and determining resectability, and the reported sensitivity and specificity are more than 80%, according to Dr. Giedre Kavaliauskiene, from the department of radiology at the Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam.

MRI is not commonly used for pancreatic cancer resectability evaluation, though it has a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 78%, she noted at the 2012 meeting of the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR). The specificity of ultrasound is significantly lower (63%). Contrast-enhanced PET/CT has a reported sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 82% in pancreatic cancer resectability assessment, and though it is not generally thought to be cost-effective as a routine staging examination, some institutions use it as an additional modality in evaluating difficult cases and for improved detection of distant metastases, according to Kavaliauskiene.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality. Surgery is the only curative method of treatment, but only 15% to 20% of patients have resectable disease at the time of diagnosis. Patients with the lowest disease stage (IA) after surgery have a five-year survival rate of 31.4%, versus 3.8% without surgery, she explained. Even with the lowest disease stages (IA and IB), median survival rate after surgical resection ranges from 21 to 24 months. For stages IIA, IIB, III, and IV, the five-year survival rate after surgery is 15.7%, 7.7%, 6.8%, and 2.8%, respectively.

"Therefore, precise pancreas cancer staging is crucial for proper patient management (surgery, neoadjuvant, or palliative treatment) and determining the prognosis. Imaging is crucial to detect potentially resectable cases and to avoid unnecessary surgery," Kavaliauskiene stated. "Accurate staging requires knowledge about the staging system used, which imaging features are important, and how these influence the management."

Staging of pancreatic cancer depends on the tumor size, local extension, lymph node involvement, and absence (or presence) of distant metastases. In imaging, the primary tumor size and lymph node metastases are the most important prognostic factors for survival -- for example, the larger the tumor, the less likely it is to be resected and for the patient to have a good survival. However, large tumors should be resected if there are no contraindications for surgery (for example, no vascular encasement), and even patients with stage III disease after surgery have a better prognosis compared to without surgery, she explained.

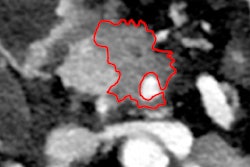

The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system gives essential guidance for adequate MDCT imaging interpretation in pancreatic cancer, especially in cases of possible tumor resection, and she urged radiologists to take notice of these guidelines. Approximately 60% of the pancreatic adenocarcinomas are found in the pancreatic head, about 15% in the body, and only 5% in the tail. Most pancreatic cancers are circumscribed masses, but they can be difficult to delineate; infiltrative involvement of the pancreas is not common. The growing pattern of this pancreatic cancer can make it difficult to distinguish from lymphoma, according to Kavaliauskiene.

"Pancreatic adenocarcinomas are usually hypodense masses compared to the normal pancreas parenchyma. They are best visualized on the late arterial/pancreas parenchymal phase," she noted. "Unfortunately, tumors can appear isodense to the pancreas parenchyma on the later portal venous phase. In these cases, the double duct sign -- dilatation of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct -- plays an important role in pancreatic head tumor detection. These ducts usually are encased and obstructed by the tumor."

Pancreatic duct dilatation helps to detect pancreas tumors in the body and tail as well. Approximately 20% of pancreatic tumors do not cause pancreatic duct obstruction, she stated.

Note: To read the full version of the presentation by Kavaliauskiene and colleagues at ESGAR 2012, click here.