Taking the audience on a whirlwind tour around a Noah's Ark of cats, dogs, rabbits, hamsters, reindeer, and snakes, a veterinary surgeon known to his thousands of television fans as the "Bionic Vet," gave a plenary lecture to remember at last week's U.K. Radiological Conference (UKRC).

Dr. Noel Fitzpatrick, director and clinical chair of Fitzpatrick Referrals in Eashing, south of London, colorfully illustrated how helping animals helps animals to help humans. Addressing clinicians more used to talks on human patients, he said he believed all forms of advanced diagnostic imaging and imaging-assisted therapeutics used in humans should be considered for small animals.

"In the past, cost was the major factor, and it still is, but it should not preclude access for those animal owners that actively seek such diagnostic modalities and the treatments made possible with them," he told a packed hall of fascinated UKRC attendees, adding that the aim of his talk was to impartsome insight into how vets use diagnostic imaging to facilitate decision-making in clinical cases that have relevance for human patients.

"People often forget that everything clinicians use has to be tested on animals first," he stressed. He then made comparisons between features of canine disease and the equivalent in humans, flashing up a collection of radiological images and photos including dogs with prosthetic limbs, osteosarcomas, three-legged animals, and fortunately some healthy dogs leaping around demonstrating the benefits of total joint replacement.

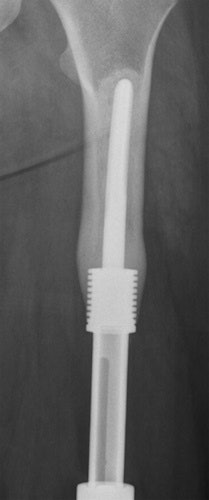

These images show treatments for osteosarcoma in a dog. Left: Radius and ulna custom modular endoprosthesis with hydroxyapatite collars and carpal arthrodesis. Right: Distal tibia custom modular endoprosthesis with hydroxyapatite collar and tarsal arthrodesis. Images courtesy of Dr. Noel Fitzpatrick.

These images show treatments for osteosarcoma in a dog. Left: Radius and ulna custom modular endoprosthesis with hydroxyapatite collars and carpal arthrodesis. Right: Distal tibia custom modular endoprosthesis with hydroxyapatite collar and tarsal arthrodesis. Images courtesy of Dr. Noel Fitzpatrick.Synthetic cartilage

About four years ago, a U.S. company wanted to launch a synthetic form of cartilage. Fitzpatrick explained to his clients that this technology was available and allowed them to choose, under control of the veterinary regulations that govern clinical practice in the U.K., whether they wanted a conventional "debridement" (clean up in the hope of a fibrocartilage scar infilling the defect), or a synthetic cartilage transplant. He said that owners have the right of fully informed volitional consent, with the proviso that the treatment is in the direct interest of that particular patient.

The material in question was polyurethane, which has been used in multiple human applications for many years with an established safety and efficacy profile, but never, until now, in joints. "Can it be any worse than having a hole in your joint?" he remarked. Fitzpatrick had previously pioneered the transplant of cartilage from the knee joint to fill such holes in the elbow, caused by a debilitating condition called osteochondritis dissecans. Synthetic cartilage was the next logical step, and by allowing owners to choose this option and monitoring the outcome using MRI with owner volitional consent, Fitzpatrick could help these clinical patients. The serendipitous by-product of this clinical application was that the technique could then be more rapidly transferred into human patients.

This is the essence of treating an animal more effectively than in the past, and then happily helping humans as well, according to Fitzpatrick. "We looked at the interface between the implant and the bone at three months, six months, and one to two years, and found the dogs did well," he said, showing the audience a photo of a happy, bounding dog and its owner.

"The images show the synthetic cartilage works. It means they can now enter clinical trials in humans with the next generation of implant, plus that next generation of implant is available for the next generation of dogs; everybody wins," Fitzpatrick said. "Animals helping humans, humans helping animals," he added, driving his point home.

He reinforced his argument with examples from other species. His colleague, Dr. James Cook, a veterinary surgeon from the University of Missouri in the U.S., has replaced the entire humeral head of a rabbit. "Can you provide it for a defect in the human knee? Yes, you sure can. It works and it's a good thing," he added.

Fitzpatrick pointed out that all total joint replacements were conducted in animals such as dogs and sheep before humans receive them. He often performs total joint replacements in dogs for all kinds of joints, including the world's first semiconstrained knee replacements for dogs and cats, and shoulder, elbow, and hock replacements.

"We're using new bearing surfaces, plastic such as PEEK on metal, which are good," he said and asked the clinicians gathered if they had seen growth in bone plastics yet. "You'll be seeing these in the next few years on appendicular MR imaging ladies and gentleman. There's no metal, just plastic. Animals have benefited first from this technology," he added.

Virtual spines

Illustrating the cross-pollination between animal and human medical research, Fitzpatrick is embarking on a four-year project with Drs. Matthew Allen and William Marras from Ohio State University in the U.S., to model a human and a canine spine. "We are going to develop a virtual model of the animal and human spines on which we can operate in virtual reality and potentially fast-forward to see what the result might be in five years."

This important sharing of information between human and animal doctors will help to provide solutions for painful conditions such as disk disease and spinal deformities, Fitzpatrick added. By working together, he proposes that both the animal and the human fields of medicine move forward more quickly.

Bone tumors in dogs and humans

Bone tumors in humans and dogs are very similar, Fitzpatrick continued. "Dogs have really helped in terms of prognostication in humans, and in terms of drug development for humans; dogs help man all the time."

Prognostic markers discovered in dogs include ezrin, a membrane-cytoskeleton linker in canine osteosarcoma associated with shorter disease-free interval, and gene expression profiling of canine osteosarcoma that has revealed genes associated with short and long survival times.

Fitzpatrick explained why understanding dog osteosarcoma was so valuable to understanding human cancers. "Human surgeons are very interestedin this because the path of the disease in the dog is far quicker, so we can do things more swiftly than in humans, meaning advances are quicker too."

The incidence of bone tumors in dogs is 10 times that in humans; gene expression in dog osteosarcoma is equivalent with regard to 265 genes of the human genome, and bone structure is similar in terms of morphology, molecular, and histologic features. This makes advances in either species -- and comparison of the disease in man and dog -- very relevant for both species. Again, "it's win-win," he proposed.

Fitzpatrick described how he operated on a dog with an osteosarcoma in the distal radius by implanting a custom endoprosthesis and the dog recovered and ran around, and is still running more than two years later. "Why is this relevant to humans?" he asked. "Well you can do bigger dogs with special collars on the end of the metal and on to these ends the bone physically grows," he explained.

Endoprosthesis collars in a human femur show the same kind of in-growth that are seen in the collars in animals. Image courtesy of Dr. Gordon Blunn, University College London.

Endoprosthesis collars in a human femur show the same kind of in-growth that are seen in the collars in animals. Image courtesy of Dr. Gordon Blunn, University College London.

"In the tibia or the radius, you can see the bone growing down around the end of the endoprosthesis," he added, showing radiographic images of the hydroxyapatite collar on the end of endoprostheses in the canine tibia, radius, and ulna (see images).

This is relevant because the same operation that is done in man's best friend can be done in man himself and may last for life. He referred to the work of Dr. Gordon Blunn at University College London, with whom Fitzpatrick collaborates. He described a little girl with an osteosarcoma who had it removed and replaced with an artificial knee. "The endoprosthesis grew inside her leg," Fitzpatrick said. "She places her leg inside an electromagnetic field and it grows as she grows. This was pioneered in animals and fortunately humans benefit too. Again, everybody wins."

Finally, appealing to a radiologist's fascination with high-technology equipment, Fitzpatrick showed a photo of a stereotactic radiation unit with a dog entering it for imaging of a frontal sinus tumor. "It's a new system of frameless guidance enhanced by 3D ultrasound. This equipment means treatment of brain and appendicular tumors are now an outpatient procedure at the University of Florida." Fitzpatrick is a courtesy assistant professor at the University of Florida School of Veterinary Medicine, and the images were courtesy of Dr. Nick Bacon who is also a pioneer in the field.

He concluded his talk by highlighting that man can learn a lot from a dog, and indeed from all animals. "We should have respect for animals in and of themselves because they are important members of each family, and in the broader sense of the family, they are teaching us new things as humans each and every day," Fitzpatrick said.

"In my opinion, this is the only rational path for medicine: to innovate and translate from man to dog and from dog to man. Please join me on this journey," he concluded.