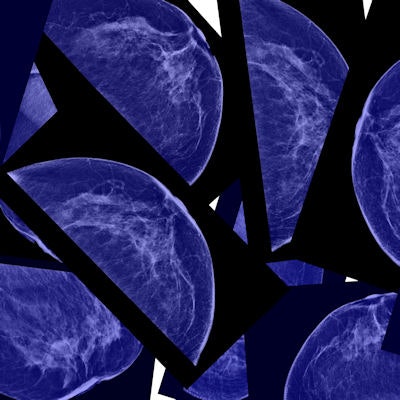

The findings of a new Danish-Norwegian study are reviving the claim that the recent drop in breast cancer mortality is not due to mammography screening but rather the result of improved treatment. The authors assert it's time to consider alternatives to mammography screening -- such as breast palpation by physicians.

While it's an accepted fact that mortality from breast cancer has been declining for the past several decades, mammography skeptics have asserted that the drop is due to better treatment, while screening proponents have countered that screening and treatment combined should take credit.

To investigate the question, a team led by Henrik Støvring, PhD, an associate professor at Aarhus University in Denmark, compared changes in mortality among women eligible for screening to concurrent changes in younger and older ineligible women. The researchers segmented the birth cohorts into three categories by age (International Journal of Cancer, 25 August 2018).

They used birth cohorts from 1896 to 1982 before screening was introduced and compared them with cohorts from 1987 to 2010 that included 4,903 women who died from breast cancer. They included women ages 30 to 89 and constructed three age groups: women eligible for screening, younger women ineligible for screening, and older women ineligible for screening.

The researchers estimated relative incidence-based mortality rate ratios in Norway comparing temporal changes in eligible women to concurrent changes in ineligible women. They also compared the change in eligible women to younger, ineligible women with either continued accrual and follow-up period or continued follow-up period.

All three age groups experienced a reduction in mortality when screening was introduced, but the decrease among eligible women was about the same among ineligible women (relative mortality rate ratio = 1.05 versus 0.94-1.18), the study authors wrote. Varying the definition of follow-up yielded similar results, they added.

"The new study shows that screening does not lead to women living longer overall -- and this is the study's most important finding," Støvring noted in a press statement accompanying the study. "The women who are invited to screening live longer because all breast cancer patients live longer, and they do so because we now have better drugs and more effective chemotherapy."

Støvring also stated his belief that mammography screening leads to overdiagnosis, in which cancers are detected that would never pose a health threat to women. He thinks the new findings indicate that alternatives to breast screening should be investigated -- one of which could be clinical breast exam.

"If a doctor could instead examine women's breasts with his or her hands, what is known as palpation, at regular intervals, then we would avoid much of the overdiagnosis," Støvring concluded.

But as is often the case in research about mammography screening, the new study's findings are drawing fire from mammography proponents. One of breast screening's most vocal defenders, Dr. Daniel Kopans, found a number of faults with the study's methodology, in particular its lack of detailed data on the patients who participated in the study.

For example, the researchers compared death rates of women in groups before and after national screening programs started, but many women may have been participating in screening on their own before they began participating in an organized program, while women who were not invited to the organized program might also have independently undergone screening.

Kopans also noted that the study authors attributed the falling death rate from breast cancer to better treatment but provided no data to support this statement.

"They have no data on treatment, so cannot conclude anything about treatment. Even biostatisticians should know this fundamental fact," Kopans said.

Finally, Kopans finds the suggestion that palpation could somehow replace mammography screening to be highly questionable.

"The death rate from breast cancer was unchanged in the U.S. for 50 years when using 'his or her hands' was practiced," Kopans noted. "It was not until screening was introduced in the mid-1980s that deaths began to fall, so that there are now 40% fewer women dying than when 'his or her hands' was the method of detection."