It's not every day that a radiology department has the opportunity to evaluate the health of a 2,000-year-old mummy, but thanks to collaboration by an international team of museum specialists, radiologists, and 3D visualization experts, an enshrouded mummy has revealed its secrets.

Visitors to the National Museum of Scotland can view the Rhind Mummy, look at images of its skeletal anatomy, fly-through movies of the CT scan images, see detailed 3D reconstructions including a facial image, and find replicas of funereal objects on its body and within linen wraps that were discovered for the first time thanks to state-of-the-art diagnostic imaging.

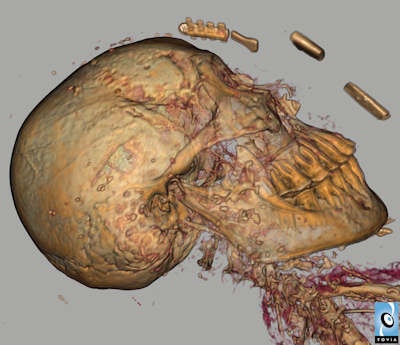

The mummy has a full set of teeth that are generally in good condition. Among other amulets on the head, there are two winged scarab amulets, one on the outer wrappings and one close against the skull beneath the wrappings that is not visible externally. Image generated from Fovia software. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland.

The mummy has a full set of teeth that are generally in good condition. Among other amulets on the head, there are two winged scarab amulets, one on the outer wrappings and one close against the skull beneath the wrappings that is not visible externally. Image generated from Fovia software. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland.This display is one of the highlights of "Fascinating Mummies," an international exhibition combining significant treasures of the Egyptology collection of the Riksmuseum van Ouheden, the Netherlands' national museum of antiquities in Leiden, and those of the National Museum of Scotland. On view until 27 May, this is one of several blockbuster exhibitions heralding the completion of a three-year long, 58 million euro ($76 million U.S.) renovation of the Edinburgh museum.

The Rhind Mummy first underwent a CT scan in 1998, using a single-slice spiral scanner (Somatom Plus, Siemens Healthcare). The 3-mm-slice-thick images reconstructed at 1 mm increments enabled forensic anthropologists to determine the mummy's gender. However, the image data had not been retained in digital format. Only x-ray films had been retained.

Jim Tate, PhD, head of the museum's conservation and analytical research department, and Dr. Edwin J.R. van Beek, chair of clinical radiology of the Queen's Medical Research Institute of the Clinical Research Imaging Center, decided that another CT exam was in order to determine if more information about features of the mummy that were unclear from the prior exam could be obtained. Also, Tate and colleagues were interested in incorporating 3D displays of the data.

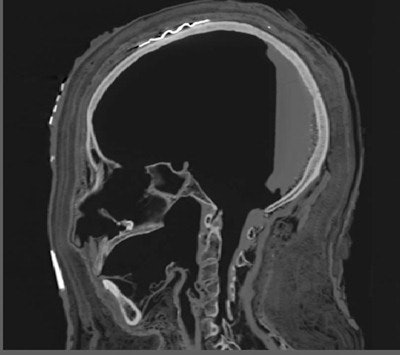

Sagittal reconstruction of the skull with amulets and mummification damage to the ethmoid sinus. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland.

Sagittal reconstruction of the skull with amulets and mummification damage to the ethmoid sinus. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland.The Rhind Mummy, unlike many excavated from Egyptian tombs, has been left intact in her linen wrappings, a decision make by its discoverer, Alexander Rhind, a Scottish Egyptologist. He discovered the mummy's tomb in Thebes (Luxor) in 1857 at the age of 24, and brought its contents in a preserved state back to the Edinburgh museum. The mummy, which dates to about 10 B.C., was left intact, as Rhind disapproved of its unwrapping.

A special transport crate was built for the event, and the mummy rode in the museum's custom-built van to the outpatient imaging center. The exam was scheduled after hours in the evening, both to prevent criticism that it was interfering with the schedules of living patients, and so that patients would not be startled by seeing a body-sized crate entering the imaging department.

The mummy was unpacked from its transport crate inside the CT scanning suite by a conservation and research team from the museum. Radiology department staff then positioned it on the scanner table.

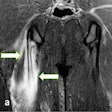

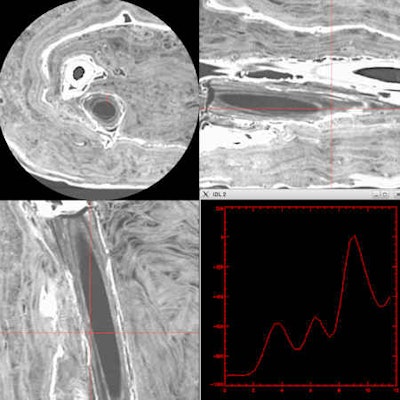

Multiplanar reformats and density spectrum demonstrate papyrus scroll behind right femur and held in mummy's hand. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland.

Multiplanar reformats and density spectrum demonstrate papyrus scroll behind right femur and held in mummy's hand. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland."We had a rough protocol for imaging in mind, but ultimately had to make additional scans based on an initial inspection of the acquired images," van Beek told AuntMinnieEurope.com in an interview. "Our plan was to use the thinnest possible slice and the largest amount of radiation dose possible so that we could acquire the best details. We did a head-to-toe body scan with a scanner that had 16 cm volume coverage. Because that's quite a lot, we presumed that the scanning would be quick."

Using a 320-slice CT scanner (Aquilion One, Toshiba Medical Systems Europe), van Beek and colleagues performed 0.25 mm volumetric imaging using two kV settings and using maximal mAs. Additional imaging of the head was performed, using a gantry tilt to allow for better reconstruction of the head and facial bones.

The entire process to image the mummy was performed within two hours, most of the time spent getting the mummy into and out of the imaging center. "Fortunately, the outpatient center is located adjacent to the hospital. It was possible to back the museum's van to the entrance, put the crate in a lift, and take it downstairs without creating any alarm," he explained.

Many hours of analysis followed. The radiology team spent a lot of time analyzing the images, working with forensic pathologist Dr. Elena Kranioti, lecturer in forensic anthropology at the University of Edinburgh and her anthropology team to perform measurements, study for potential cause of death or trauma, reconstruct the face, and clarify detailed information on findings discovered within the shroud.

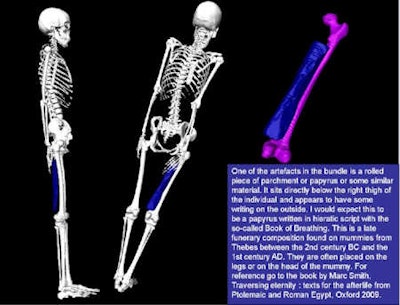

3D reconstruction of the mummy and papyrus role using Amira software. Images courtesy of and copyright of Elena Kranioti.

3D reconstruction of the mummy and papyrus role using Amira software. Images courtesy of and copyright of Elena Kranioti.Martin Connell, a clinical scientist at the Clinical Imaging Research Centre, did the initial 3D reconstruction using Voxar 3D visualization software. Dr. Saeed Mirsadraee, a senior clinical lecturer in radiology at the University of Edinburgh, did subsequent image postprocessing.

Two separate videos were made one of detailed 3D reconstructions and the other of a high definition volume rendering fly-through of the whole body scan (HDVR Connect software, Fovia) . "We wanted the rapid 3D interaction of Fovia's software to give the fly-through appearances, whereas we used Voxar software more for the actual measurements and to highlight some of the key findings of the mummy," van Beek said.

The mummy was an Egyptian woman in her late 20s, according to Kranioti, who led the analysis of data to determine the mummy's age, sex, stature, health, and ethnicity. She was approximately 158 cm (62 inches) in height. She appeared to be healthy at the time of her death, the cause of which could not be determined. Her teeth were well maintained, with minimal tooth decay, which meant that she had been eating relatively refined foods that did not contain any sand.

A metal amulet showing a flying scarab was identified on the woman's forehead, presumably made of pure gold. The exhibition contains a replicate of this. Several other amulets were identified, on and within the linen wrappings.

The wrapped mummy imaged from the CT scans showing the visible amulets using Fovia software. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland.

The wrapped mummy imaged from the CT scans showing the visible amulets using Fovia software. Image courtesy of and copyright of the National Museum of Scotland.Most exciting was the discovery that a scroll, presumably a funerary text made of papyrus containing the mummy's lineage or name, directions for mummification, and guidance for the afterlife, had been placed in her right hand resting on a thigh."We were able to reconstruct the dimensions and the position of the scroll, and we are having discussions as to whether micro-CT may be able to make this legible," van Beek said. A team of specialists from Toshiba Medical Visualization Systems Europe performed the scroll reconstruction.

In addition to the Rhind Mummy, two other mummies of animals were scanned. A crocodile mummy did in fact contain the skeleton of a crocodile. But a mummy that had an image of a baboon turned out to be an ibis. "Seeing a beak and the bones of birds instead of a monkey was a real surprise -- and a thrill for everyone," van Beek concluded.

The project originated from a request relating to a 15th century Celtic harp. A doctoral student in music at the University of Edinburgh who was interested in recreating the sound of the harp, approached the radiology department to ask if two harps from the National Museum of Scotland's collection could have a CT scan. The objective was to determine the thickness of the wood and analyze how the harp had been made. This project and several other projects imaging artifacts established a link between the museum and the Clinical Research Imaging Centre of the University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian.