To make real progress in sports imaging, radiologists must look beyond the "dark box" and collaborate with referring doctors, attend multidisciplinary meetings at the hospital, discuss cases with clinical colleagues, and get feedback on the radiology report and direct correlation with arthroscopic findings, according to Dr. Claudia Weidekamm, an associate professor of radiology at the Medical University of Vienna.

Sound anatomical knowledge also is crucial, noted Weidekamm, who was a speaker at today's transatlantic course on sports imaging. She has learned a lot from orthopedic conferences and fruitful discussions with physiotherapists and surgeons, she said.

"It is important to know that each joint forms a musculotendinous-osseous unit that allows movement in certain directions and to understand the function of each joint in order to interpret the injury pattern with typical associated pathologies in the correct clinical setting," she told ECR Today. "For example, in patients with anterior shoulder dislocation, look carefully for pathologies at the anteroinferior labrum/glenoid."

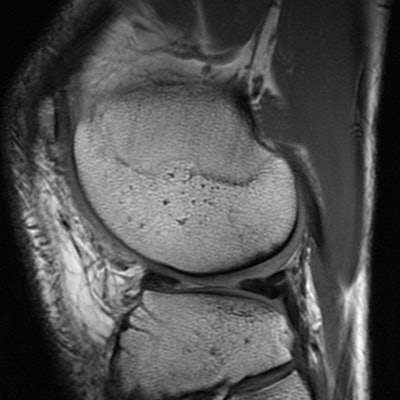

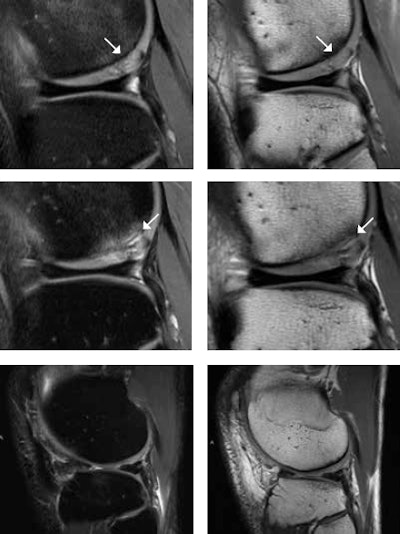

A 25-year-old male tennis player after microfracturing (MFX), or bone drilling. With MFX, small holes 3- to 4-mm apart from each other are drilled into the subchondral bone to stimulate the bone marrow (stem cells). MR images one year after MFX (top row) show persistent mild subchondral bone marrow edema and high T2 signal change of the cartilage (white arrows) at the posterior portion of the lateral femoral condyle. At two-year follow-up (middle row), there is progressive subchondral bone marrow edema, undermining fluid at the interface between the subchondral bone and the cartilage, and interstitial tears of the detached cartilage (white arrows). This is consistent with incomplete integration of the chondral defect. MR images four years after MFX (bottom row) surprisingly show complete integration of the chondral defect without any additional treatment. Images courtesy of Dr. Claudia Weidekamm.

A 25-year-old male tennis player after microfracturing (MFX), or bone drilling. With MFX, small holes 3- to 4-mm apart from each other are drilled into the subchondral bone to stimulate the bone marrow (stem cells). MR images one year after MFX (top row) show persistent mild subchondral bone marrow edema and high T2 signal change of the cartilage (white arrows) at the posterior portion of the lateral femoral condyle. At two-year follow-up (middle row), there is progressive subchondral bone marrow edema, undermining fluid at the interface between the subchondral bone and the cartilage, and interstitial tears of the detached cartilage (white arrows). This is consistent with incomplete integration of the chondral defect. MR images four years after MFX (bottom row) surprisingly show complete integration of the chondral defect without any additional treatment. Images courtesy of Dr. Claudia Weidekamm.Ultrasound still plays an important role in sports injuries, as an immediately available on-the-field imaging modality at sports events and also as a complementary modality for assessing muscle and tendon injuries or post-traumatic effusion/synovitis. "Nowadays, we face the problem that ultrasound is performed more and more by sonographers. The consequence is that radiologists are losing their skills for performing the ultrasound examination," she noted.

Ultrasound is an excellent high-resolution imaging modality to investigate nerve entrapment syndromes that can occur after trauma or as sequelae of overuse injury in athletes. In ankle injuries, ultrasound supports the clinical examination of ankle instability and can differentiate between partial or full-thickness ligament tears.

"To encourage young radiologists to improve their ultrasound skills, we organize interdisciplinary musculoskeletal ultrasound and MRI courses in Vienna and in Auckland, with a special focus on sports injuries," said Weidekamm, who added that the next course runs in Auckland from 21 to 23 March 2019.

At present, she is taking a sabbatical in New Zealand, working for TRG Imaging in Auckland, and she has noticed that significant differences exist between how sports injuries are approached in Austria and New Zealand.

For instance, the interpretation of knee MRI examinations in New Zealand tends to focus on the differentiation between acute and chronic findings, and this is related to the insurance system. Every New Zealand resident is enrolled in the insurance system for accidents without any extra costs, but the insurance covers only the costs for the diagnosis and treatment that are related to a specific accident. Weidekamm explained that here is quite often a fine line between acute injuries and pre-existing disorders that result in osteoarthrosis -- e.g., related to anterior cruciate ligament deficiency or meniscus tears.

To develop skills in sports imaging, involvement in sporting events also can be valuable. In 2007, her group investigated the knees of Vienna city marathon runners, before and after the race.

"The teaching point was the direct collaboration with patients and their clinical findings and a better understanding of pre-existing findings on MRI that were related to their intense training prior to the run," she recalled. "It is crazy how much the athletes punish themselves and train through their pain. I understand that most of the athletes struggle with reducing their training program during the preparation for the race, though they have incredible pain."

Looking to the future, Weidekamm is excited about the fusion of different imaging modalities. For example, combining ultrasound with MRI or CT promises to lead to many new options for minimal interventional therapy. Anatomic structures that have not been properly visible on ultrasound can become accessible with the support of CT or MRI to mark adequate landmarks, and the advantages of each imaging modality can be consolidated to achieve a correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment, leading to the best possible outcome for the patient.

Originally published in ECR Today on 2 March 2019.

Copyright © 2019 European Society of Radiology