The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) in combination with permanently evolving imaging techniques and machines has created a complex working environment, and there is an ever greater need for radiographers to create strategies to optimize the patient's clinical pathway and be prepared to develop skills to keep their profession alive. At today's session SF12d, ECR delegates will hear about the risk of the machines taking over if radiographers don't fully develop their role and underline the added value of their services.

Interacting with patients, creating a safer environment, and providing a more effective and objective service for referrers are key to safeguarding the profession's future, according to Graciano Paulo, head of the scientific board of medical imaging and radiotherapy at Coimbra Health School in Portugal. Radiographers should prioritize adapting to today's reality and focus on communication and teamwork, he explained.

"If we don't position ourselves, then radiographers will become merely the interface of a technical service, becoming obsolete as robots learn to do the same job. However, we can bring more than this to the profession, assuring the irreplaceable 'human touch' in patient management," Paulo told ECR Today ahead of the congress.

In terms of risk communication, the amount of time spent with each patient is the biggest challenge due to the increasing volume of procedures and the demand for more rapid access to diagnostic imaging. "We must guarantee not just the most adequate diagnostic and therapeutic procedures but also the provision of all the necessary information about risk in a harmonized way," he noted. "Furthermore, we have to make sure we have anxious patients' attention and adapt what we say accordingly. This is one of the things that differentiates us from the machines."

The WHO guidance document on communicating radiation risk aims to help radiographers harmonize communication strategies.

The WHO guidance document on communicating radiation risk aims to help radiographers harmonize communication strategies.Paulo also underlined the need for proven "whole-procedure" metrics to serve as an indicator for how long examinations should take. It is important to ensure adequate time is allocated for explanations and obtaining fully informed consent, and studies should be undertaken to measure how many procedures radiographers can safely perform over a set period of time. The metric tool would also analyze each patient's radiation exposure, as well as time for the radiographer to communicate with the radiologist or referrer about any postprocedural treatment issues, such as for tissue reaction.

These metrics would produce an adequate average time per examination that would cover explanations and also factor in time spent answering patients' questions after the procedure and communicating with referrers.

Furthermore, whole procedure metrics can serve as a guidance tool, incorporating input from all professionals on the patient pathway, according to Paulo. He stressed that "point of care" should be the same across the European Union (EU), pointing to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidance document on communicating radiation risk as an excellent starting point for the harmonization process.

At today's session, Lee O'Hora, radiation safety officer at the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin, will cover different strategies for harmonizing risk communication to patients within facilities. Speaking to ECR Today ahead of the congress, he said that in his country a large majority of imaging outpatients are seen by radiographers, making these professionals the most appropriate people to explain risks and procedures. Furthermore, around 70% of all radiology referrals are for plain film imaging, meaning that the only medically trained staff that these x-ray patients see in the department is the radiographer.

Revealing to patients that an x-ray is 10 mGy/m2 may not be that helpful when communicating risk.

"Effective dose should be translated into something tangible for patients to grasp, such as 'background radiation.' I tend to explain it in terms of days or weeks -- or for heavier exposure, months," O'Hora noted.

Every facility should provide its own bespoke analogies, depending on where it falls in terms of the national average. In the Mater, for example, one chest x-ray equals one day of background radiation in Ireland, compared to the national figure of two days.

He added that radiographers should opt for scenario comparisons taken from daily life. "Most patients aren't worried about the associated radiation effects of being in an airplane 30,000 feet up in the air. If they are not worried about the radiation on a flight from Dublin to London, then you can let them know that they probably shouldn't be worried about a diagnostic procedure."

A keen proponent of metrics, O'Hora points to the imaging department's motto ("What gets measured, gets managed") as a key factor in making the Mater a low-dose facility. Evidence from his doctoral research, however, suggests that not all hospitals in the EU have the same dose parameter awareness about the specific parameters used to quantify risks associated with different procedures, and this might pose problems for optimal communication to patients.

He sent a questionnaire to European interventional physicians and radiographers about using dose parameters to quantify and qualify effects of radiation. In some categories of the questionnaire, the majority of respondents provided incorrect answers. O'Hora believes ongoing training is vital, particularly in the interventional suite, where staff need to be aware of the double risk of stocastic effects and tissue reactions in their exchange with patients.

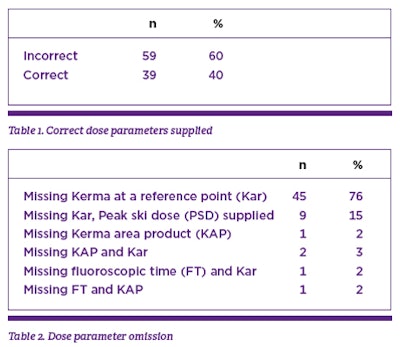

The tables show the results of a questionnaire sent to European interventional physicians and radiographers, focusing on operators' knowledge of dose parameters and indicators in interventional radiology. When asked to quote the model and dose parameters available for equipment, 60.2% of 98 respondents answered incorrectly. This was mainly due to the omission of kerma (kinetic energy released per unit mass) at a reference point (Kar), an important dose parameter for the identification of potential patient tissue reactions after a procedure. Tables provided by Lee O'Hora.

The tables show the results of a questionnaire sent to European interventional physicians and radiographers, focusing on operators' knowledge of dose parameters and indicators in interventional radiology. When asked to quote the model and dose parameters available for equipment, 60.2% of 98 respondents answered incorrectly. This was mainly due to the omission of kerma (kinetic energy released per unit mass) at a reference point (Kar), an important dose parameter for the identification of potential patient tissue reactions after a procedure. Tables provided by Lee O'Hora.The EU Basic Safety Standards (EU BSS) Directive also may necessitate changes to how risk is communicated and raises the question of who will be responsible for this under national legislation.

"In the new directive, radiographers are only mentioned once, and then we are largely ignored or overlooked. This is a serious omission of the European legislation," he said. "The EU Federation of Radiographers has been working to rectify the situation. New regulations that will be applied in 20 years time will mention the role of radiographers more clearly, but in the current standards, responsibility for communicating risk has been allocated to the practitioner and referrer. This is somewhat short-sighted."

Originally published in ECR Today on 2 March 2018.

Copyright © 2018 European Society of Radiology