VIENNA - For suspected late postoperative complications in the abdomen, CT can provide swift and accurate diagnoses in what may be life and death situations. Such a diagnosis by radiologists is vital for the choice of therapy route, whether this is conservative treatment or emergency surgery, delegates heard at Sunday's session on gastrointestinal (GI) tract imaging.

"So what to do when it still hurts?" asked replacement moderator Dr. Anno Graser, head of oncologic imaging at University Hospital of Munich, using the example of patients admitted to emergency departments with pain, up to two years after gastrointestinal surgery. "The patient may not fully remember, so don't rely on the patient for a history of what was done," he warned.

Long-term postsurgical complications include both procedure- and disease-related complications, the latter often pertaining to recurrent disease.

Adhesions and internal hernias are among the most frequent late complications after procedures, and these can be compounded by bowel obstruction, particularly closed loop, and by strangulation, and ischemia, which may necessitate immediate surgical response. The radiologist must therefore know the radiological signs, which are not always common - or recognized by radiologists when evaluating postoperative patients with CT.

Adhesions may present as an acute angulation and narrowing of the bowel loop without any underlying cause such as bowel wall thickening or mass, according to speaker Dr. Luís Curvo-Semedo, a consultant radiologist at Coimbra University Hospital in Portugal.

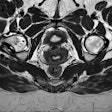

Care must be taken to compare views, delegates learned. Demonstrating this was a case in which abnormal bowel loops depicted in an axial view indicated something wrong but it was unclear exactly what. Coronal images showed a narrowing of a small-bowel loop causing obstruction, related to a postsurgical adhesion.

According to Curvo-Semedo, it was possible to differentiate two types of adhesion: obstructing and nonobstructing. Nonobstructing adhesions are harder to see on CT, he noted, pointing to the potential role of MRI in their detection. Obstructing adhesions, simple, closed loop, and strangulated were easy to detect and characterize by CT. Typical imaging findings for an adhesion included an abrupt narrowing of the small bowel.

"You may be lucky enough to see the adhesive band itself," he told delegates, pointing to a fat band crossing a small-bowel loop. "This is the so-called 'fat-bridging' sign, which is very suggestive of adhesion."

To ensure high-quality visualization, investigations with CT should include two injections of intravenous contrast with a 60-second delay between each but no oral contrast. In addition, datasets should be thin sections that can then undergo 3D reformatting.

The other common complication, internal hernia, is typically visualized with an absence of fat between the dilated loops and the abdominal wall, and also the lateral position of the small bowel in relation to the colon, Curvo-Semedo continued.

"Usually, the colon is at the periphery of the abdomen. Instead, you will have the small bowel at the periphery of the abdomen," he said.

With strangulation, twisting both of the bowel loops and the vessels themselves will be accompanied by signs of ischemia -- a thickening of the bowel wall. There may also be diminished enhancement of the bowel wall, as well as igns of necrosis, which include gas in the bowel wall and the portal and mesenteric veins.

In the case of immediate complications following GI procedures, surgeons were concerned with knowing whether they would need to reoperate. It was not only imperative for radiologists to know normal and abnormal scan appearance postsurgery, but also the key interventional management in case of complication, according to Dr. Damian Tolan, consultant GI radiologist at St. James's University Hospital in Leeds, U.K.

"Postoperative CT is very difficult and you have to make it as easy for yourself as you can, so use your best scanner. Don't use the old single- or four-slice scanner. You need the all-singing all-dancing 64 or 128. And give contrast if you can, because that makes differentiation of normal from abnormal much easier," Tolan said. "Most importantly, get as much information as you can before you do the scan at all."

Tolan referred to his TV hero Dr. House, a character inspired by the legendary detective Sherlock Holmes, who always hunts for the truth and only eliminates a possibility from a process once it is logically proved impossible. "An open mind is a key attribute for postoperative imaging," he added.

House's notion that "everybody lies" may have some truth to it when it comes to medical colleagues describing how long ago surgery took place and also the clinical status of a patient.

He urged radiologists to ask surgeons the right questions, such as the following: What operation did you do? What is your primary clinical diagnosis -- what are you worried about with this patient? How long ago did you operate?

In addition, when clarifying with the surgeon which procedure was undertaken, Tolan echoed Napoleon's dictate that "a good sketch is better than a long speech."

"Particularly where the patient has had a complex operation, get the surgeon down and ask them to draw exactly what they did."

The reason is because a two- or three-stage operation may determine how far up the thorax the radiologist should scan. Furthermore, radiologists should find out if there was anything unplanned that happened during the procedure, such as bleeding or injury. Modifications to the standard technique or intraoperative injury may help identify specific complications.

CT protocols varied depending on the complication suspected. In the case of sepsis versus leak, radiologists were treated to Tolan's trick of picturing the Autoroute A8 in France.

"Think about your route of contrast administration and use 8% contrast. It is really important to fill your patient up with contrast if you are querying a leak on CT."

Every patient's nightmare of undergoing surgery only to have foreign material left in the body from the procedure proved a lively part of the lecture on postsurgery imaging presented by Dr. Michael Maher, consultant radiologist at Cork University and Mercy University Hospitals in Cork, Republic of Ireland. Accidentally left material, as well as that deliberately left by surgeons, often unmentioned, such as Surgicel, features specific radiological signs but needs careful interpretation.

Surgicel, for example, presents as a low-attenuation "mass" on CT with punctate, often peripheral gas foci that could be misinterpreted as abscess. However, it shows no contrast enhancement and is visualized as hypointense on T2-weighted MRI compared with abscesses, which are hyperintense.

Meshes might be hard to discern, depending on their composition. Interventional coils and dropped gallstones also could yield confusing radiological features that erroneously might suggest bullet wounds or carcinomatosis.

"When you see peculiar things, consider foreign bodies or a hemostatic agent," Maher said. "We should never treat an 'image.' We should discuss the case with the surgeon and correlate the clinical findings before a major decision is made."

Originally published in ECR Today on 10 March 2014.

Copyright © 2014 European Society of Radiology