The fiercely contested race to demonstrate how artificial intelligence (AI) can improve quality of care and patient outcomes began on the opening day of RSNA 2019, when the latest clinical evidence of AI's potential value in breast screening came under the microscope.

"The whole AI area is a new world," Mark Halling-Brown, PhD, head of scientific computing at Royal Surrey County Hospital in Guildford, U.K., told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "Research shows AI to be as good as a single radiologist -- we were never sure if we would ever get to that point, and I'm very excited about the progress that has been made to date."

At Sunday morning's session, he presented the findings of a retrospective study about AI's accuracy in detecting breast cancer. The trial used 2,683 screening mammograms from Optimam, an image database of over 80,000 digital images extracted from the U.K. National Breast Screening System (NBSS). The images used were biopsy-proven, screen-detected cancers.

Of the screen-detected cases, 1,969 presented with invasive cancers and 670 contained ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) only. There were a total of 1,001 presented grade 3 cancers, 1,186 grade 2 cancers, and 314 grade 1 cancers.

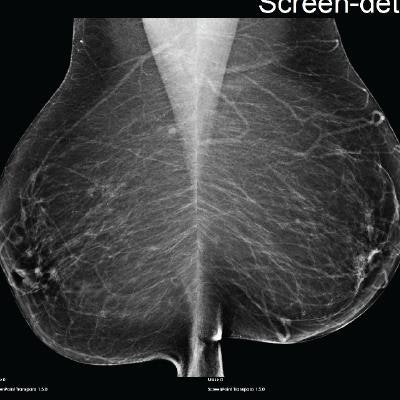

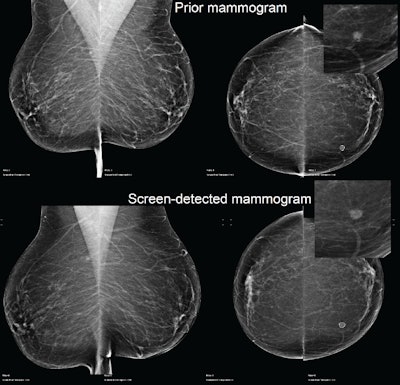

Example of a case of an invasive ductal carcinoma grade 2 screen-detected cancer in the left breast. The AI system recalled both the screen-detected mammogram and the prior mammogram -- read as normal three years earlier -- when operating at the recall rate of the U.K. screening program (4%). Image courtesy of Mark Halling-Brown, PhD.

Example of a case of an invasive ductal carcinoma grade 2 screen-detected cancer in the left breast. The AI system recalled both the screen-detected mammogram and the prior mammogram -- read as normal three years earlier -- when operating at the recall rate of the U.K. screening program (4%). Image courtesy of Mark Halling-Brown, PhD.Each mammogram was analyzed by an AI system (Transpara, ScreenPoint Medical). The software, which received 510(k) clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 2018, produced a decision at different recall rates. Recall-rate calibration was established for a typical screening population with another set of independent data, but the mammograms in this study were never before used to train, validate, or test the AI system, according to Halling-Brown.

He reported that the AI system had a sensitivity for screen-detected cancers of 99.3%, 87.7%, and 76.1% at recall rates of 50%, 10%, and 4%, respectively.

A key benefit of the software is that researchers can set their own recall rate, he added. They chose 50% as one of the units so they could see how it performed as a triage tool in those cases that were deemed to be normal, although using AI as a triage tool is not possible in the U.K. yet because all scans must be read by humans.

In the U.K., two radiologists read screening mammograms, and the average recall rate is around 4%, but Public Health England is working on new guidance to help AI developers understand the process for incorporating new technologies into screening programs, Halling-Brown explained. The U.K. National Screening Committee has approved interim guidance for the use of AI in breast screening.

Despite the new study, he remains unsure how quickly AI can be adopted clinically due to the issues over generalizability.

"Most AI products require a dataset upon which it can be trained, but in the U.K. it is a real challenge to get large volumes of highly curated datasets, where all clinical information is attached to the case," he said. "When you train the algorithm, you have to tell it where the cancer is. That's really valuable information because the algorithm can focus on learning what a cancer looks like rather than focusing on what an entire case looks like."

Also, Halling-Brown conceded that the set of images used to gather the latest data was not ideal. "What we haven't done yet is to challenge the AI algorithm with a diverse generalizability problem, but this is the next step," he said.

Unanswered questions

Commenting on the U.K. study, Dr. László Tabár, professor emeritus of radiology at Uppsala University Faculty of Medicine in Sweden, said it fails to address some essential questions.

"There are 12 different subtypes of in situ carcinoma, so when the authors refer to cases that are so-called DCIS, which of the subtypes have they based their stats on?" he told AuntMinnieEurope.com.

"Why have they not chosen tumor size and mammographic appearance (imaging biomarker) instead of histopathologic malignancy grade? Histopathologic malignancy grade has no prognostic value if I find a unifocal acinar adenocarcinoma of the breast tumor in the size range of 1-9 mm," Tabár added. "Most of all, what was the tumor size of their stellate versus circular tumors?"

The problem is that researchers often sit behind a desk and try to figure out something based on numbers, without having sufficient real-life experience about breast cancer and its complexity/heterogeneity, he stated.

Upbeat perspective

Dr. Alyssa Watanabe, who spoke at the same RSNA session, is more positive than Halling-Brown about the speed of AI's implementation.

"AI is real: It's happening now, it's routine, and it's installed," said Watanabe, chief medical officer and director of clinical research at CureMetrix, a startup based in San Diego, California, U.S. "In the next 10 years, most imaging will be analyzed beforehand by machine."

Faced by a shortage of qualified breast radiologists, a growing incidence of burnout, variations in interpretative performance, more diagnostic delays and false-positive recalls and biopsies, and increasing volumes and complexity in screening, AI can help to improve outcomes, she noted. Perhaps triage rather than computer-aided diagnosis is the answer today, she added.

Commercially available, FDA-approved mammography triage software can analyze and sort cases, and it is viable as a standalone technique to handle a high percentage of screening mammograms from the worklist, according to Watanabe. The main potential benefits are faster recall of patients and optimized workflow, improved accuracy (radiologists can spend more time on suspicious cases), higher productivity (more efficient reading and elimination of low-suspicion cases), improved distribution of cases in a group practice, and more worklist control.

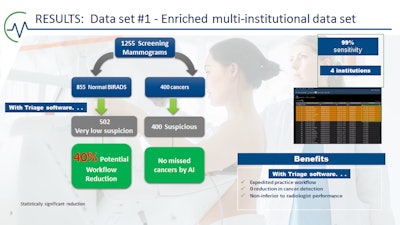

To underline the promise of breast AI, she presented her own group's recent findings.

Forty percent of noncancer cases were sorted as "normal," with no missed cancers, and 100% of cancers were triaged into the suspicious category. Image courtesy of Dr. Alyssa Watanabe.

Forty percent of noncancer cases were sorted as "normal," with no missed cancers, and 100% of cancers were triaged into the suspicious category. Image courtesy of Dr. Alyssa Watanabe."The machine is not inferior to radiologists," said Watanabe, noting that Rodriguez-Ruiz and colleagues have shown AI can achieve a cancer detection accuracy comparable to that of an average breast radiologist; however, AI performed consistently lower than the best radiologists in all datasets (Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 1 September 2019, Vol. 111:9, pp. 916-922).

Some of the terminology used when introducing AI in breast screening can be misinterpreted, she continued. For instance, the term "average radiologist" may be used when comparing reading outcomes between humans and computers.

"Not everyone is expert; the average radiologist isn't perfect and may not detect up to 15% of breast cancers," Watanabe said.

CureMetrix's AI software is used in clinical practice in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Mexico, and Brazil. Also, the nonprofit radiology organization Rad-Aid is looking at installing AI in parts of Africa, she said.

Watanabe recommends that purchasers of AI should "try before they buy." They need to "get the software into their hospitals for a trial time to see how it runs on their own databases and whether it integrates with their own PACS, to see if it solves the problem before committing to any specific system."

To help radiologists decide which type of software is best suited to their needs, the American College of Radiology has produced a type of buyers guide, which consists of a list of FDA-approved AI software. Watanabe cautioned, though, that simply having FDA clearance does not necessarily indicate a green light to go ahead and purchase.