Recently, I read an article in Radiology about the feasibility of virtual autopsy and postmortem CT angiography and biopsy.1 The Swiss authors have been developing the virtual autopsy, otherwise known as virtopsy.2

This concept is not as new as some people may think, however. Many years ago, Dr. William J. Morton,3 and then H.C. Orrin,4 emphasized the superiority of the x-ray method to conventional dissection when demonstrating vascular anatomy. Orrin also stressed the value of stereoscopy, which is 3D imaging and has its modern equivalent in CT angiography with 3D reconstructions. I am sure Orrin would have simply loved postmortem CT angiography.

Figure 1: First angiogram by Haschek and Lindenthal, taken in January 1896.

Figure 1: First angiogram by Haschek and Lindenthal, taken in January 1896.Postmortem CT angiography is a natural development from CT angiography, which in turn developed from conventional angiography. Traditional angiography was pioneered by the Portuguese radiology school in the 1920s.5 Angiography itself developed from postmortem angiography.

The first procedure was performed in January 1896 by Haschek and Lindenthal who injected a calcium carbonate emulsion (Teichmann's mixture) into the severed arm from a cadaver (figure 1). The arteriogram exposure was for 57 minutes, which is not unreasonable when one remembers the low power of the apparatus that was then available.

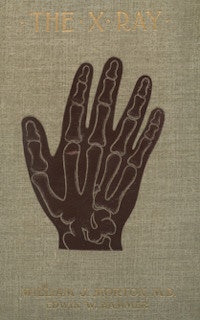

Figure 2: The X-Ray or Photography of the Invisible (William J. Morton).

Figure 2: The X-Ray or Photography of the Invisible (William J. Morton).

This procedure was performed in Vienna, and during ECR 2013, I was able to see the original radiograph at the museum in the Josephinum. The museum has its origins in the Museum of Austrian Medicine and was founded by Max Neuburger.6 It's a lovely small museum with a radiological section. The centerpiece is the six rooms with the 18th century "Collection of Anatomical and Obstetric Wax Models."

The angiographic work in Vienna was soon followed by the work of a group in Sheffield, U.K. William M. Hicks, who was the principal of Firth College in Sheffield, and Dr. Addison achieved both a renal and a hand arteriogram. They injected the specimens with red lead and their results were published later that month in the British Medical Journal on 22 February 1896.7

And now comes the really interesting part. Morton was an important early figure in radiology in the U.S. He went by the grand title of "professor of diseases of the mind and nervous system and electro therapeutics" in the New York Post Graduate Medical School and Hospital. I have a copy of his book, The X-Ray or Photography of the Invisible.2 My copy is not dated, but it must have been published in 1896/7 (figure 2).

Morton makes the following very pertinent observation:

In teaching the anatomy of the blood vessels the x-ray opens out a new and feasible method. The arteries and veins of dead bodies may be injected with a substance opaque to the x-ray, and thus their distributions may be more accurately followed than by any possible dissection. The feasibility of this method applies equally well to the study of other structures and organs of the dead body. To a certain extent, therefore, x-ray photography may replace both dissection and vivisection. And in the living body the location and size of a hollow organ, as for instance the stomach, may be ascertained by causing the subject to drink a harmless fluid, more or less opaque to the x-ray, or an effervescent mixture which will cause distension, and then taking the picture.

I have quoted this at length because I think Morton's words are so fascinating. In this very early book, he's predicting contrast gastrointestinal studies, and also the use of radiology in the equivalent of virtopsy. The pioneers so often get it spot on.

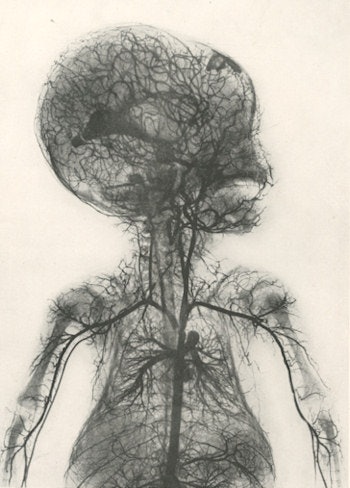

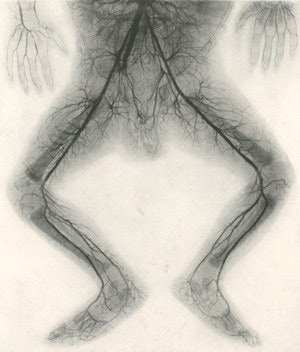

The first systematic x-ray atlas of the arteries was by Orrin and was published in 1920.3 The book is beautifully illustrated with stunning radiographs (figures 3 and 4). Orrin writes that, "No matter how well dissection is performed, complete continuity of the vessels; their exact relationship to bones; their finest terminal branches; the series of anastomosis into which they enter are seldom if ever accurately displayed or intelligently appreciated by dissection alone." He echoes Morton.

Figure 3 (left): Systemic vessels of the superior half of the body (Orrin 1920). Right: Figure 4 (right): Systemic vessels of the inferior half of the body (Orrin 1920).

Figure 3 (left): Systemic vessels of the superior half of the body (Orrin 1920). Right: Figure 4 (right): Systemic vessels of the inferior half of the body (Orrin 1920).The atlas was accompanied by a set of stereoscopic radiographs (figure 5), "which provide the only possible means of accurately rendering visible the points and details specified."

It was Egas Moniz and other Portuguese radiologists who produced practical angiography. Moniz was aware of the pioneering work of the Frenchmen Jean Sicard and Jacques Forestier in angiography. Moniz initially tried to opacify the brain itself and then performed arterial injections. Again, his first angiogram was the postmortem injection of a 30% NaI solution into a preserved head in 1927.

','dvPres', 'clsTopBtn', 'true' );" >

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 5: Stereoscopic radiographs of head and neck, thorax, and abdomen (Orrin 1920).

Dr. Adrian Thomas is chairman of the International Society for the History of Radiology and honorary librarian at the British Institute of Radiology.

References

- Ross SG, Thali MJ, Bolliger S, Germerott T, Ruder TD, Flach PM. Sudden death after chest pain: Feasibility of virtual autopsy with postmortem CT angiography and biopsy. Radiology. 2012;264(1):250-259.

- Thali M, Dirnhofer R, Vock P, eds. The Virtopsy Approach: 3D Optical and Radiological Scanning and Reconstruction in Forensic Medicine. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2009.

- Morton WJ. The X-Ray: Or, Photography of the Invisible and Its Value in Surgery. London, U.K.: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd.; 1896.

- Orrin HC. The X-Ray Atlas of the Systemic Arteries of the Body. London, U.K.: Bailière, Tindall, and Cox; 1920.

- Thomas A. Let's recognize and pay homage to Portuguese genius. AuntMinnieEurope.com website. http://www.auntminnieeurope.com/index.aspx?sec=sup&sub=xra&pag=dis&ItemID=607454. Accessed 16 April 2013.

- Museum at the Josephinum. Medical University of Vienna website. http://www.josephinum.meduniwien.ac.at/organisation/museum-at-the-josephinum/en/. Accessed 16 April 2013.

- Anonymous. The new photography in Sheffield. BMJ. 1896;495-496.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.