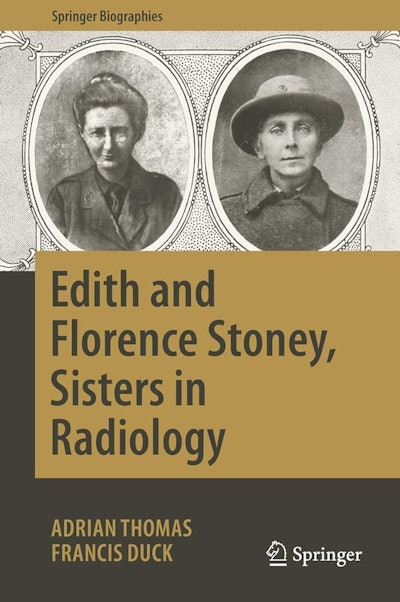

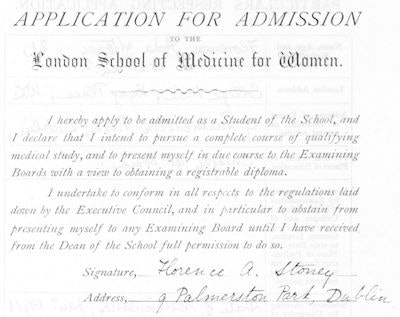

Dr. Florence Stoney, the U.K.'s first female radiologist, was born in 1870 in Dublin. In the late 19th century, women could not study medicine in Ireland so she came to England, attending the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW) and graduating in 1895. For six years, she was demonstrator in anatomy at the LSMW, and only stopped when it became apparent that there was no possibility of a woman being appointed to a lectureship.

"We horrified the French by insisting on fresh air," Florence Stoney wrote.

"We horrified the French by insisting on fresh air," Florence Stoney wrote.

In 1902, Stoney founded the x-ray departments at the Royal Free Hospital and the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in London. The conditions were primitive. She often took the plates home and developed them in her bathroom in the evenings, doing all the work herself.

At that time, the radiologist was not a member of the hospital's medical staff, and she was not a member of the committee that discussed the work of radiology. Her practice was varied and included examinations for foreign bodies, bullet wounds, and fractures, as well as examinations for tuberculosis and various treatments. In 1907, the Royal Free appointed Dr. Harrison Orton to take charge of a combined department of radiology and electrotherapy, an appointment made over the head of Stoney.

In 1913, Florence visited the U.S., remarking, "I found the doctors in America, both in the hospitals and in private, very ready to allow me to see the work in their departments -- medical women not being kept out of everything so much as in England." She noted a major concern for radiation protection, and nowhere was the operator left unexposed to radiation apart from fluoroscopy, of which there was only a limited use.

She described the use of a mirror to observe the fluorescent screen with the operator being protected. The newly invented Coolidge x-ray tube was seen in frequent use. The Coolidge tube is the modern type of tube with a hot spiral cathode and high vacuum that replaced the older cold cathode gas tubes. Significantly, she brought back a new Coolidge x-ray tube, which was only the second to arrive in England.

On 4 August 1914, the opening day of World War I, Stoney offered her services to the British Red Cross, but in spite of 13 years of experience in radiology, her offer was refused because she was a woman.

She "wasted no time with arguments or indignation," and along with Mrs. St. Clair Stobart, she organized a voluntary women's unit that was established by the Belgian Red Cross. The unit was entirely staffed by women, and Florence was the principal medical officer and radiologist. In September 1914, they went to Antwerp and set up their all-women's hospital, described as "a model of organization."

The Stobart Hospital had 100 beds, was located in an old concert hall, and was established before the "official" British Army hospitals had been set up. On 8 October 1914, they were under shellfire for 18 hours and their situation was desperate. They evacuated their patients, then started to walk to Holland and were picked up by three London buses and had to sit on ammunition cases. Stoney escaped from Antwerp only 20 minutes before the bridge was blown up. She continued work in France at the Chateau Tourlaville near Cherbourg. Radiography was used to show the positions of the fractures and the location of the shrapnel and bullet that could then be extracted.

"We horrified the French by insisting on fresh air, with the result that all visitors, medical as well as lay, remarked how ruddy and well our patients looked, unlike the white faces you see in most of the hospitals," Stoney wrote. "The consulting surgeon for the whole of the Cherbourg district came to see our hospital, thinking it was a waste of time to go to a place only staffed by women doctors, but after spending a couple of hours going thoroughly round the wards he wrote that 'L'Hôpital de Tourlaville est très bien organisé, les malades sont très bien soignés, et les chirurgiennes sont de valeur égale aux chirurgiens les meilleurs. [The Tourlaville Hospital is very well organized, the patients are very well cared for, and the surgeons are of equal value to the best surgeons.]' "

The patients were also appreciative and Lance-Corporal F. Reynolds of the 2nd Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry said in the Daily News on 9 January 1915 that "lady doctors do all the work -- no men at all, so you can guess I am all right. George and I were the only two spared out of six in our trench. Don't you think I had a fine birthday?"

In March 1915, Stoney was appointed head of the x-ray and electrical department of the Fulham Military Hospital, and she was the first woman doctor to work under the War Office in England. She was honored for her war work, and she also received the 1914 Star with bar as given for service under fire.

Florence Stoney received several awards and medals during her career.

Florence Stoney received several awards and medals during her career.

Florence Stoney's signature.

Florence Stoney's signature.Her health had suffered, partly related to exposure to radiation. During her career she was concerned with women's health issues, such as the treatment of fibroids and the diagnosis of pelvic deformities in women due to osteomalacia that would cause problems in childbirth. In retirement, she traveled to India to investigate osteomalacia and it was the subject of her last scientific paper. Stoney died in 1932 at the age of 62. According to one observer, she had "a gentle kindness and rich sympathy for suffering -- showed courage in her own last, long, and painful illness."

Stoney had a firm faith in the potential capacity of women to fill positions of the highest responsibility. She felt that women should develop their powers to the highest possible extent and then, if opportunity failed them, they should make their own opportunity. She was a keen suffragette and took part in many demonstrations and processions in support of women receiving the vote. In personality, she was shy and retiring with a quiet manner. This was combined with an iron will and undaunted courage. Her gentle graciousness disarmed opposition and gained cooperation for "few had dreamt of the ardor existing beneath that demure and gentle exterior." In professional matters, she was very keen to pass on all that she learnt. She was innovative in her approach to radiology and was involved in many early x-ray developments. Her life story would make a great Hollywood blockbuster, with Kate Winslet playing Stoney, of course! She was a remarkable woman, and we should remember her with gratitude for her pioneering work in our specialty.

In a special history session at the UKIO congress in Liverpool at 13:45-14:45 on 12 June 2024, Kimberley Bradshaw, a lecturer in Medical Imaging Sciences at the University of Cumbria, will speak about "Florence Stoney - formidable feminism in the history of radiology." Other talks will be about "Double indemnity - the arrival of the digital twin," Dr Michael Jackson, NHS Lothian/British Society for the History of Radiology; "John Poland of Blackheath and the development of paediatric orthopaedics," Dr. Adrian Thomas, Canterbury Christ Church University; "The million-volt radiotherapy x-ray set at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1938," Adrian Thomas; "Francis H Williams – an American radiology pioneer," Dr. Arpan K Banerjee, British Society for the History of Radiology. For more details, go to https://www.ukio.org.uk/programme-2024/

Women were unable to study medicine in Ireland in the late 19th century, so Stoney set her sights to London.

Women were unable to study medicine in Ireland in the late 19th century, so Stoney set her sights to London.Dr. Adrian Thomas is chairman of the International Society for the History of Radiology and honorary librarian at the British Institute of Radiology. He is a visiting professor at Canterbury Christ Church University.

This article was first published by AuntMinnieEurope.com on 6 November 2011. The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.

Further reading

- Thomas AMK. Florence Stoney and Early British Military Radiology. In Der durchsichtige Tote -- Post mortem CT und forensische Radiologie. Eds. H Nushida, H Vogel, K Püschel & A Heinmann, Verlag Dr. Kovač, Hamburg. 2010:103-113.

- Obituary: Florence A Stoney. Brit J Radiol. 1932;5(59):853-858.

- Stoney FA. X-ray notes from the United States. Arch Roentg Ray. 1914;19:181-184.

- Stoney FA. The Women's Imperial League Hospital. Arch Roentg Ray. 1915;19:88-393.