Heavy cannabis use in adolescence to early adulthood is associated with volumetric differences in subregions of the hippocampus and amygdala, researchers from New Zealand have reported at the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) annual meeting in Toronto.

"The lack of detectable cerebral blood flow and white-matter tract integrity differences associated with cannabis is interesting," noted medical physicist Rebecca Lee and colleagues from the New Zealand Brain Research Institute, University of Otago, Christchurch. "This may suggest that cannabis use has no long-term effect for these properties, or any potential brain changes may be transient and detectable only during periods of use."

Direction of causation and the extent to which these structural brain changes mediate the effect of cannabis on long-term functional outcomes is not clear, but they may emerge from longitudinal studies, they added.

Growing dependence on cannabis

Cannabis (or marijuana) is one of the most widely used illicit drugs worldwide, and by 21 years of age, 80% of New Zealanders will have tried it at least once, with 10% going on to develop a pattern of heavy use or dependence, the researchers pointed out, adding that societal attitudes toward the medical and recreational use of cannabis are becoming increasingly tolerant.

According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the proportion of the U.S. population over 12 years of age who used cannabis in the past year increased gradually from 11% in 2002 to 18% in 2019. Around 36% of 12th graders and 43% of college students reported using it in the past year.

Around 183 million people in the world used cannabis in 2014, and 22 million met criteria for cannabis use disorder in 2016. Also, the potency of cannabis products -- as measured by the concentration of the primary psychoactive constituent of marijuana, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) -- rose from about 4% in 1995 to 15% in 2018 in the U.S.

"Cannabis use is associated with varying effects on learning, attention, temporary hallucinations, paranoia, disorganized thinking, and short-term memory loss," the authors noted in an ISMRM poster. "MRI studies have also suggested cannabis-related structural and functional changes in temporal regions; however, they are often inconsistent and not necessarily associated with the short-term effects of cannabis use."

Study logistics

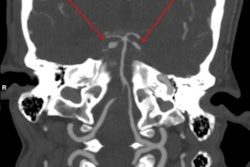

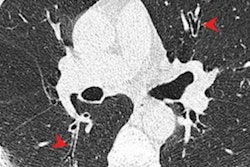

Lee, a PhD candidate focusing on the use of MRI to study how past heavy cannabis exposure impacts an aging brain, and her colleagues used structural T1-weighted, arterial spin labeling (ASL), and diffusion MRI to investigate the long-term effects cannabis exposure has on brain volume, cerebral perfusion, and cerebrovascular health.

They recruited 69 participants from the Christchurch Health and Development Study, a longitudinal study of people born in Christchurch in 1977, followed from birth. Of the sample, 35 were past cannabis users and 34 were non-using controls. All participants were scanned on a Skyra 3-tesla MRI unit from Siemens Healthineers.

Significantly smaller volumes were found in the past cannabis users in hippocampal subregions -- CA1 (Cohen's d = 0.66 [0.17, 1.14]), hippocampal fissure, molecular layer, presubiculum, and subiculum, as well as in the amygdala subregions -- lateral, paralaminar, basal, and accessory basal nuclei (Cohen's d = 0.81 [0.31, 1.3]). No significant group differences (corrected p < 0.05) were observed in any perfusion or white-matter integrity metrics in the hippocampus or amygdala, or in whole-brain analyses.

"Our results of smaller hippocampal and amygdala subregional volumes are consistent with previous short-term follow-up studies, and suggest that volumetric brain differences are still observable in middle-aged adults with a history of cannabis use," the researchers stated. "Conversely, there was no evidence of differences in cerebral perfusion or white-matter integrity amongst people with heavy cannabis exposure."

Compared with non-using controls, users exhibited significantly less grey-matter volume in the hippocampus and amygdala (p < 0.05). No significant between-group differences in cerebral blood flow or white-matter integrity. While cannabis may relate to long-term brain changes, prospective longitudinal MRI studies may help to elucidate causality.

Structural brain changes associated with heavy cannabis use were found, but the study does not conclusively show these changes are causally related to cannabis use, they concluded.

Lee and her colleagues are currently working to secure funding to extend their work to a large cohort of about 1000 people in their mid 40s.

The group's ISMRM 2023 poster is to be discussed in exhibition halls D/E on 6 June. They received funding support from the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Canterbury Medical Research Foundation, Pacific Radiology Christchurch, and the MedTech CoRE.