DUBLIN - The management of patients with chronic coronary artery disease (CAD) is moving rapidly from simple diagnosis to guidance of therapy and the prevention of future cardiac events, Dr. Juhani Knuuti, PhD, the director of the Turku PET Centre at Turku University Hospital in Finland, told delegates at the World Molecular Imaging Congress (WMIC).

Molecular imaging will improve the characterization of vulnerable plaques, as it can provide additional information on the biological activities occurring within these structures, but multiple challenges must be met before it can be routinely adopted, he said in a keynote address at the conference. Available animal models in mice, rabbit, and pigs have shortcomings. In mouse models of atherosclerosis, for example, the plaques do not rupture, while diet-induced pig models are time-consuming and expensive, even if the scale of the animals is similar to that of humans, he explained.

More prospective trials are needed to determine the clinical value of plaque characterization, according to Dr. Juhani Knuuti, PhD. All images courtesy of Brendan Lyon, ImageBureau, imagebureau.ie.

More prospective trials are needed to determine the clinical value of plaque characterization, according to Dr. Juhani Knuuti, PhD. All images courtesy of Brendan Lyon, ImageBureau, imagebureau.ie.

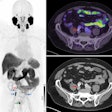

Available tracers are also not optimized. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (F-18 FDG) is still the most sensitive tracer. "The problem is, of course, the nonspecificity of the signal," Knuuti said. Others that have utility include F-18 galacto-RGD, the uptake of which correlates with macrophage density in murine plaques, F-18 EF5, a marker of hypoxia, F-18 choline, and PK-11195, a ligand for the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. However, their kinetics are not suitable for in vivo imaging.

Atherosclerosis imaging has been employed as a surrogate end point in drug trials. For example, F-18 FDG PET/CT assessment of arterial inflammation was used in both the dal-Plaque trial of dalcetrapib and in the Glacier study of BI-204. Data from several other studies employing the same technique are imminent.

Nevertheless, the field remains at an early stage of development. "We need more prospective trials to determine the clinical value of the plaque characterization," Knuuti concluded. "One of the key issues is how often do you have these active plaques in stable disease versus nonstable disease?"

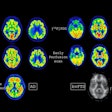

These advances are important because existing risk factors for predicting a heart attack -- such as age, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, angina, diabetes, smoking, and family history, as well as blood biomarkers, such as levels of C-reactive protein -- are still unable to distinguish CAD patients who will experience acute coronary syndrome from those who will remain stable. "I think imaging can play a major role in the future," he said.

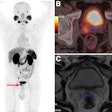

Knuuti and his colleagues have demonstrated that PET/CT can be used to detect CAD.

Knuuti and his colleagues have demonstrated that PET/CT can be used to detect CAD.

A major focus of imaging research in this area is on the identification and characterization of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques, which are most prone to rupture. These have several distinguishing characteristics, including a large necrotic lipid core, a thin fibrous cap, dense macrophage infiltration, progressive matrix degradation, a paucity of smooth muscle cells, a hot angiographic signal, and inflammation. Patients only have a small number of these -- typically one to three -- but they are large in volume and are generally located in the proximal segments of coronary arteries.

At present, vulnerable plaques are only routinely accessible using invasive techniques, such as intravascular ultrasound, which requires catheterization, and optical coherence tomography imaging. "The optical imaging resolution is much higher, so you can really define the cap thickness," he explained. "Still, this is invasive and not very much used in the clinical routine." Also, invasive methods are not practicable for future screening applications.

Noninvasive techniques used to assess plaques include multidetector CT and MRI of carotid arterial plaques, although evidence gained to date of their predictive value is not conclusive. Knuuti and colleagues have demonstrated that PET/CT, which combines angiography and perfusion imaging, can be used to detect CAD, even though each modality on its own had no predictive value.