The benefits of music exposure on mental performance and cognitive development are a long-held and somewhat evidenced belief, encouraging some parents to enroll their children in music lessons when they are barely out of nappies. Brain imaging experts now go further by saying that amateur and professional musicians have physical differences in their neural images compared with nonmusicians and that there is a distinct difference in brain activity when the brain is imaged while a subject is playing music.

But are these image differences just differences, or do they signify improvement in brain function and cognitive skills? Just how does music impact our most important "human" organ?

This was the subject of a lecture held on 17 September at music association and concert venue La Loingtaine, near Fontainebleau in Paris. The presenter was neuroscientist and radiologist Prof. Denis Le Bihan, PhD, founding director of NeuroSpin at the French Nuclear and Renewable Energy Commission at Saclay, as well as a high-level amateur pianist.

"What is happening in our head when we listen to a piece of music? Or when we play an instrument or when we compose? Where does this musical 'frisson' come from?" Le Bihan asked. "Cerebral imaging today allows us to take a close look at our brain to study its anatomy and function and its relationship with music."

Prof. Denis Le Bihan is a keen musician. Here he is playing on Ravel's piano.

Prof. Denis Le Bihan is a keen musician. Here he is playing on Ravel's piano.The musician's brain develops from a very young age and presents several particularities that differentiate it from the brain of a music lover or a nonmusician, he told attendees. With functional MRI (fMRI), neuroimaging can shed light on the musical brain even if it still retains some mystery, he said.

"Neuroimaging shows that the thickness of definite regions of the brain cortex is thicker in musicians, and there are changes in the anatomy of white matter which underlines brain connectivity as well, according to the number of hours of practice," Le Bihan told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "Specific regions are activated when one listens to music and when one plays it. Owing to brain plasticity, by playing music you modify your brain wiring and there is some evidence of the benefits."

The imagined world

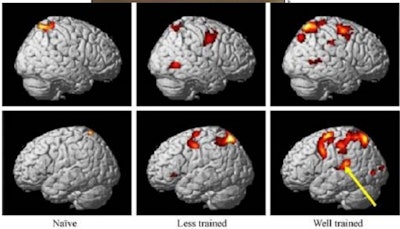

Research shows that pianists who read a score will 'hear' the music in their minds, and certain brain areas responsible for listening (such as the auditory cortex) will be activated through this imaginative leap. Furthermore, when asked to imagine playing a piece, the motor cortex of the brain is also activated.

Because of the plasticity of the musician's brain, pianists or violinists, for example, can practice their instrument without the physical instrument in front of them. Le Bihan added that pianists watching another pianist play the piano without actually hearing what is being played will "hear" the music in their head, also activating the auditory cortex.

Brain areas activated by just looking (without sound) at a pianist playing a musical piece. Well-trained musicians activate a network of regions connecting visual, auditory, and motor areas, such as the inferior frontal gyrus and in experienced pianists, mainly the planum temporale. Figure courtesy of Prof. Denis Le Bihan reprinted in his book "Le cerveau de cristal" (Odile Jacob Ed.) with permission from Hasegawa et al. Cogn Brain Res 2004, 20, 510-518).

Brain areas activated by just looking (without sound) at a pianist playing a musical piece. Well-trained musicians activate a network of regions connecting visual, auditory, and motor areas, such as the inferior frontal gyrus and in experienced pianists, mainly the planum temporale. Figure courtesy of Prof. Denis Le Bihan reprinted in his book "Le cerveau de cristal" (Odile Jacob Ed.) with permission from Hasegawa et al. Cogn Brain Res 2004, 20, 510-518)."The brain is a simulator and will constantly fill in the gaps, or calculate the best way to protect you," Le Bihan explained. "In the 1990s, fMRI studies showed that the imagination is enough to activate different cortexes: If you mentally picture a cat the visual cortex is activated, or if you read the word Wednesday so you hear it in your mind, the auditory cortex is activated, if you imagine moving your finger, the motor cortex is activated."

People with schizophrenia also show an activated auditory cortex when they "hear" their other voices, and this link between the imagined and the real worlds is particularly at play in musicians, he added.

Innate musicality?

There is a narrative to occidental music and a distinct meaning to the different tonalities used, he continued: A major key, for example, may denote happiness and triumph, while a minor key may be associated with sadness, fear, or uncertainty.

Nobody has to learn this, according to Le Bihan. Even nonmusicians feel what they are supposed to feel when hearing music in a certain key. They can also understand instinctively if, in the middle of a piece of music, the musician makes a mistake and plays a wrong note. Here, an fMRI may show that the median prefrontal cortex gets activated.

"An interesting question would be to find out whether occidental tonal music is genetically imprinted in our brain as 'natural' or the result of repeated exposure to it," he said.

The good news is we don't all have to be virtuosos. Even if you are not a musician, the brain can still benefit from music.

Le Bihan pointed to a May 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In two cohorts of premature babies born at six months term, the babies that were exposed to music on a daily basis for three months until they reached what would have been full term, showed functional differences in large networks of areas involved in emotion processing and social interactions compared to the cohort that wasn't exposed to music. Also, the former cohort later fared better in cognitive performance tests than the latter cohort.

The same author group is due to publish another study this year, this one looking at grey- and white-matter structural changes in musically exposed babies.

"The objective of art is not to reproduce nature, but to recreate a mental world evoking the emotions it gives us," Le Bihan said. "As humans we want to feel something. When we listen to music a network of brain areas linked to pleasure that bring us reward, motivation, euphoria, and emotion are activated as they are through food, sex, and drugs -- but without the risk of obesity, diseases, and dangerous chemicals."

Quoting actress Phylicia Rashad, he added: "Before a child speaks, they sing, before they write, they paint, as soon as they stand, they dance. Art is fundamental to human expression."

Le Bihan's 17 September lecture was organized at the invitation of La Loingtaine's coordinator Masako Saulière.

Editor's Note: Look out for our video interview with Prof. Le Bihan from the French national radiology congress, JFR 2022, which begins on 7 October.