Imagine being woken from sleep in the early morning by a phone call, not to tell you to come to the hospital to perform emergency imaging on a patient, but to tell you to flee your home as your country is under attack from a hostile nation. This was the experience of radiologist Dr. Nataliia Nehria, medical director of MRT Plus in Kyiv, whose brother called her on the morning of 24 February urging her to leave the city.

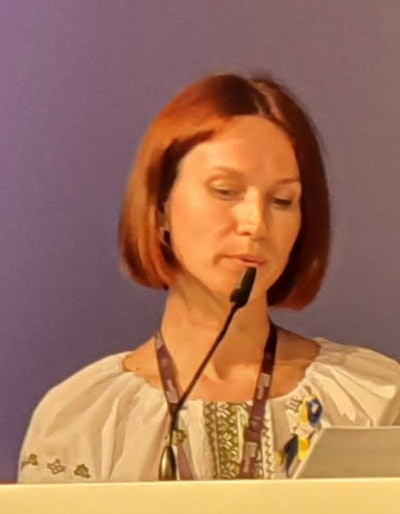

Dr. Nataliia Nehria. Image courtesy of Dr. Volker Lapczynski of Oslo, Norway.

Dr. Nataliia Nehria. Image courtesy of Dr. Volker Lapczynski of Oslo, Norway."He said 'Get up, there is war in the county. Putin, Russia has attacked us! The first rockets have landed in Kyiv!' " Nehria told participants at the meeting of the ESSR in Rostock, Germany last week.

By 10 p.m. the next day, Nehria, her 14-year-old daughter, Nehria's sister, her sister-in-law, and their children had set off on an arduous journey of nearly 1,000 km to relative safety in the west of Ukraine. The family spent 22 hours on the road and terrifyingly encountered a line of Ukrainian tanks being mobilized to defend the city. Her husband, brother, and parents remained behind in Kyiv.

"I pray every day that God will protect them. I live from air raid siren to air raid siren, from SMS to SMS. I volunteered with the war effort because helping others distracts you from the news and the pain. The realization that you are useful, that you can help those who defend your country, gives you hope for the future," she told delegates.

Home front

While in the west of the country helping with the war effort, Nehria learned that her husband had been mobilized. Until this point, he had been a normal surgeon in a civilian hospital. Now he was serving as a military surgeon on the front line alongside soldiers. Each day, Nehria waited for a text message, hoping to hear that he was still OK. Sometimes, her husband had no mobile phone connection for two days. In a team of 10 women, her own duties involved traveling to Zachon, a Hungarian border city, to collect humanitarian aid from Munich and transport it to Ukraine, transferring it to trains, which would then take it to hot spots such as Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Irpin. The group also collected money to buy military necessities such as binoculars, lanterns, knee pads, walkie-talkies, and helmets, which they would pass on to volunteer fighters and the military.

While on duty, Nehria's husband contacted her one day to suggest she go to Berlin, where the couple had old friends who had trained with them at medical school in Ukraine. Nehria left with her daughter for Berlin on 4 April. Her sister and sister-in-law, both lawyers, returned to their work for the government in Kyiv, her sister taking her 10-year-old daughter with her. With school over, the child continues with her rhythmic gymnastics training as much as possible during the day, but the family sleeps in shelters at night when the alarm sounds. Her sister-in-law's 19-year-old daughter, meanwhile, was able to go to Munich, where she is studying chemistry.

"I am so angry and wholeheartedly hate those who ruined our dreams and plans, who separated families, who butchered people, who raped women. My parents live 20 kilometers from Bucha. But how many such 'Buchas' are there in Ukraine? It's an indescribable emotional pain -- and sometimes it becomes physical," Nehria said.

Images of destruction in Ukraine. Images courtesy of Dr. Nataliia Nehria.

Images of destruction in Ukraine. Images courtesy of Dr. Nataliia Nehria.While she is grateful and relieved that her family has managed to survive, has friends nearby, and has also made new good friends, she thinks of those who have lost everything. After over 100 days of war, many people on both sides have been killed and wounded.

"Part of me feels sorrow for Russian mothers and wives who bury their sons and husbands, but they seem to be inactive -- and it was their choice to fight. What is the price of this war? For whose ambitions do they pay with the lives of their sons and husbands?" she stated.

During her presentation, Nehria asked delegates to observe a moment of silence in memory of those killed in this war and in others. She also extended thanks from the people of Ukraine to other countries for unequivocally condemning the invasion, and taking an anti-war position, noting that neutrality was inaction.

"Now Ukraine is defending peace for Europe, in our and your home at the cost of the lives of our sons and daughters, our brothers, husbands, parents, at the cost of our cities: Mariupol, Bucha and others. Just think about it: Ukraine and the Ukrainian military, the Ukrainian people have given us the chance to have a peaceful professional meeting here," she said.

Refugee specialists

While applauding the help given to Ukrainians by Europe and other countries, she believes in a two-way street that would allow Ukrainians to give back, she told AuntMinnieEurope. This might involve some leeway for allowing Ukrainian specialists to work as doctors in their host countries. Nehria herself has been a radiologist for 13 years and director of four centers -- in Kyiv and in the western cities of Rivne Lutsk and Kovel -- since 2019.

Ukraine radiologists undergo six years of training and then 1.5 years as radiology residents. So far, their diplomas are not accepted in the European Union, she noted. There is also a language barrier for those entering different countries. Nehria herself started learning German two months ago. When she attains a B2 (intermediate) level, she can apply for permission to work as a doctor's assistant, then over two years she will have to pass a general medical exam for approval of her Ukrainian diploma. Meanwhile, she receives a living allowance from the German government like all Ukrainian refugees.

"I really don't know when I can go back home, because it is still unsafe in Kyiv. I don't want to waste time while I'm here, so that is why I am learning German and I'll try to validate my diploma," she said.

However, she believes that the procedure could be simpler and more flexible for specialized doctors.

"I completely agree that we must learn German, Polish, or whatever the language of the host country is. But learning can be faster if you work and perhaps have hospital-based language classes. I think it is easy understanding language when you have contact with native staff and patients during work," she noted, adding that pairing up with a native speaker "buddy" in the department for face-to-face and telephone chat could help boost one's language level. She has received such one-to-one support in German from a musculoskeletal colleague.

Nehria calls for people to give feedback to the European Union (EU), asking the EU to be more flexible in accepting Ukrainian degrees and credentials.

Nehria calls for people to give feedback to the European Union (EU), asking the EU to be more flexible in accepting Ukrainian degrees and credentials.She also pointed out that the language barrier also applied to Ukrainian patients and that it was stressful for German doctors to have to deal with patients who didn't speak German.

"In this case Ukrainian doctors can help. I think that it is possible to implement Ukrainian doctors in any host country's medical system. I'm not sure that an exam pertaining to general medicine can show a doctor's real professional level. So while I definitely agree with extra training, it needs to be adapted to the specialty," she said.