CT and x-ray are playing a significant role in enabling doctors in Turkey to triage patients who've suffered injuries in Syria. A new article shows how imaging can help children injured by explosions. The authors think their findings may be useful for everyone working in war-torn regions.

"Radiologists who triage mass injuries should understand the effects of blast injuries patterns and the spectrum of injury," wrote Dr. Inan Kormaz, a radiologist at Hatay Mustafa Kemal University hospital in Antakya (Antioch) in southern Turkey (Clinical Radiology, 22 April 2022).

More than 2 million children have been killed in conflict zones worldwide over the past 10 years, and an estimated 86% of fatal blast injuries are due to shockwave (barotrauma) from explosions. Bomb blasts are a threat to civilians of all age groups, but children are less likely to survive than adults, the authors noted.

Hatay Mustafa Kemal University hospital is located 70 miles from Aleppo in Syria and is one of the main tertiary hospitals in the region where the wounded are first brought from the border, across which the Syrian civil war has been raging for 11 years. Kormaz and colleagues, who included two pediatric surgeons, studied x-ray and CT imaging in 74 children with musculoskeletal and accompanying organ injuries admitted between 2015 and 2020.

Blast injuries are caused by the combined effects of excessive pressure created by explosive weapons and accompanying secondary effects. The force of the excessive pressure itself is sufficient to cause injury, but secondary and complex injuries can also occur due to shrapnel fragments, impact injuries after being thrown, or injuries after the collapse of buildings, the authors wrote.

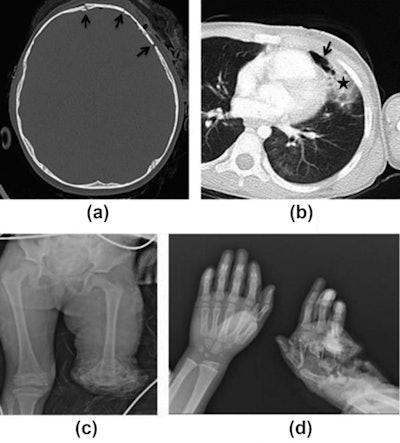

CT and radiography images of a 4-year-old girl with primary blast injury. CT images show multiple skull fractures (black arrows) in the cranium (a) and areas of pneumothorax (black arrow) and contusion (black star) in the left lung (b). (c,d) Radiographs of the same patient show left lower extremity and left hand fifth finger amputation, carpal bone fractures, and tissue defects. Image courtesy of Clinical Radiology.

CT and radiography images of a 4-year-old girl with primary blast injury. CT images show multiple skull fractures (black arrows) in the cranium (a) and areas of pneumothorax (black arrow) and contusion (black star) in the left lung (b). (c,d) Radiographs of the same patient show left lower extremity and left hand fifth finger amputation, carpal bone fractures, and tissue defects. Image courtesy of Clinical Radiology.The mean age of the group was 9 years. Of the 74 patients, findings revealed 29 (39.2%) suffered primary blast injuries (PBIs), 32 (43.2%) had secondary blast injuries (SBIs), and 13 (17.6%) had complex blast injuries. Twenty-three (31.1%) were girls and 51 (68.9%) were boys. Radiography was performed in 32 (43.2%) patients and CT in 55 (74.3%).

Based on the study, Kormaz and colleagues developed six main recommendations for radiologists who may see similar trauma, as follows:

- Blast injuries, regardless of type, can cause skeletal injuries to all body parts in children

- Due to its scattering feature, shrapnel can cause fractures in many different regions in the same patient, which requires careful radiological examination

- Presence of amputation on radiographs should prompt radiologists to suspect vital organ injury and prompt additional radiological investigations

- If there is shrapnel in the abdominal region in radiographs, the clinician should be warned of the intra-abdominal organ injury and CT should be undertaken if necessary

- The radiological images of children with skull fractures should be carefully examined for brain injury

The authors noted that the mean age in the group with primary blast injuries (7.13 +/- 3.8) was lower and there was a statistically significant difference compared with the group with secondary blast injuries (11.3 +/- 3.8), which indicates that small children may be more sensitive anatomically and that they may be thrown by the impact of blast pressure due to their small body size.

Limitations of the study included that some children had incomplete history due to the absence of their families and language problems, and some of the data were recorded under intense emergency room conditions and so may have been prone to human error.

Ultimately, the most common injury in military conflicts and civilian terrorist activities is musculoskeletal trauma, and war-related extremity injuries in children constitute a large part of the care in war hospitals, the authors wrote.

"The present analysis of the radiological images of child victims of PBIs and SBIs highlights the central role of radiology in blast injuries and the need for a multimodal imaging approach," Kormaz and colleagues concluded.