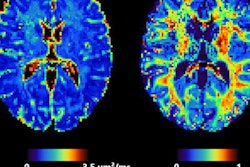

Even mild SARS-CoV-2 infection may negatively affect brain function over time, manifesting in decreases in gray-matter thickness and brain size on MRI scans, according to a U.K. study published in Nature.

The findings are sobering, since they suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection could lead to further disease as patients age, wrote a team led by Gwenaëlle Douaud, PhD, associate professor at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences at Oxford University.

"[Our results] raise the possibility that longer-term consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection might in time contribute to Alzheimer's disease or other forms of dementia," the group noted in the paper, posted on on 7 March.

Most research on brain imaging and SARS-CoV-2 has focused on acute cases of COVID-19, Douaud and colleagues wrote. But studies about how even mild infection from the virus may affect patients over the longer term are few. To investigate this, the researchers used data from 785 U.K. Biobank participants who underwent two MRI exams with an average of 141 days in between. (U.K. Biobank is a study that explores the effects of genetic predisposition and environmental exposure disease development; it began in 2006.)

"With the data from this large, multimodal brain imaging study, we use for the first time a longitudinal design whereby participants had been already scanned as part of U.K. Biobank before getting infected by SARS-CoV-2," the team wrote. "They were then imaged again, on average 38 months later, after some had either medical and public health records for COVID-19, or had had two positive rapid antibody tests."

Of the 785 study participants, 401 were positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection between the two scans and 384 were healthy controls.

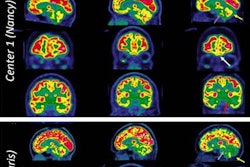

The investigators found that those patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection showed differences compared with healthy controls in the following brain regions:

| Percentage of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients who showed greater long-term brain changes compared with healthy controls | |

| Brain region | Percentage difference |

| Temporal piriform cortex | 56% |

| Olfactory tubercle | 62% |

| Left parahippocampal gyrus | 57% |

| Left olfactory tubercle | 60% |

These differences manifested in increases in time needed to complete numeric and alphanumeric cognitive tasks, the team noted.

"The infected participants also showed on average larger cognitive decline between the two time points," Douaud's team reported. "These mainly limbic brain imaging results may be the in vivo hallmarks of a degenerative spread of the disease via olfactory pathways, of neuroinflammatory events, or of the loss of sensory input due to anosmia."

The study may be the first to investigate long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to the researchers.

"To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal imaging study of SARS-CoV-2 where participants were initially scanned before any had been infected," they wrote. "Our longitudinal analysis revealed a significant, deleterious impact associated with SARS-CoV-2 ... [which] could be seen mainly in the limbic and olfactory cortical system."

As the COVID-19 pandemic enters its third year, it's clear that more research is needed regarding its long-term effects, Douaud and colleagues concluded.

"Whether [these] deleterious [impacts] can be partially reversed, or whether these effects will persist in the long term, remains to be investigated with additional follow up," they wrote.