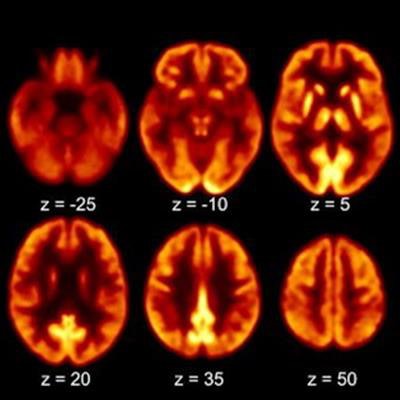

Patients with long-term symptoms from COVID-19 continue to be hampered by impaired cognitive functions, yet PET imaging has revealed the cause appears to be unrelated to any pathological changes in the brain, according to a study published on 14 October in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

German researchers at the University of Freiburg performed follow-up F-18 FDG PET scans in a group of long COVID-19 patients after initially reporting their cognitive impairment appeared related to changes in their brain glucose metabolism. Up to seven months later, the same patients continued to report significant cognitive problems, yet PET scans showed no significant changes in their regional cerebral glucose metabolism, the researchers found.

"An exhaustive assessment including a detailed cognitive battery showed only mild impairment in individual patients and cerebral F-18 FDG-PET failed to reveal a distinct pathological signature," wrote first authors Drs. Andrea Dressing and Tobias Bormann and colleagues.

"This clearly deviates from previous findings in subacute COVID-19 patients," the authors wrote.

In a study published online March 31, the researchers used FDG-PET scans to measure neocortical glucose metabolism and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test to measure cognitive function in COVID-19 patients once they were no longer infectious (subacute stage) and six months after the onset of symptoms (chronic stage).

In comparison with a control cohort, the researchers found that although both measures improved, patients exhibited residual hypometabolism and average MoCA performance rates within the range of mild cognitive impairment.

"Although a significant recovery of regional neuronal function and cognition can be clearly stated, residuals are still measurable in some patients six months after manifestation of COVID-19," the researchers concluded.

In this study, the team included all 31 patients from the initial analysis. All 31 patients continued to seek neurological counseling with neurocognitive symptoms persisting up to seven months after their initial F-18 FDG-PET scans. Patients were again assessed with a neuropsychological test battery and imaging was performed in 14 patients.

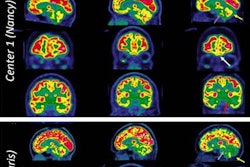

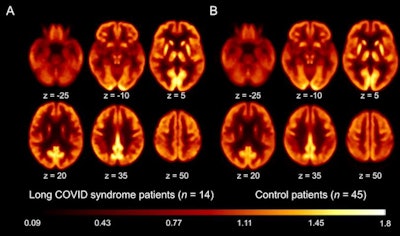

Transaxial sections F-18 FDG PET scans in patients with long COVID-19 (A) and control patients (B). Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

Transaxial sections F-18 FDG PET scans in patients with long COVID-19 (A) and control patients (B). Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.All 31 patients self-reported impaired attention, memory, and multitasking abilities. Twenty-seven patients reported word-finding difficulties and 24 reported fatigue. Twelve patients could not return to the previous level of independence/employment.

For all cognitive domains, the average group results of the neuropsychological test battery showed no impairment, but deficits (z-score < -1.5) were present at the single-patient level, mainly in the domain of visual memory, the researchers found.

In the subgroup of patients who underwent F-18 FDG-PET, the authors reported no significant changes of regional cerebral glucose metabolism.

"This clearly deviates from previous findings in subacute COVID-19 patients, suggesting that underlying neuronal causes are different and possibly related to the high prevalence of fatigue," they wrote.

Fatigue is a common symptom of systemic viral infections and was particularly prevalent in this study's cohort (61%), the authors stated. Studies in long COVID-19 patients have linked fatigue to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, which is characterized by functional impairment (e.g., disability to work) in a considerable number of patients, they wrote.

Taken together, it is tempting to speculate that the pathophysiological background of self-reported cognitive symptoms, disability, and even mild impairments in the neuropsychological test battery in single patients is primarily caused by fatigue, the researchers suggested.

Nonetheless, the lack of significant findings on F-18 FDG-PET and only mild impairments on neuropsychological testing stands in stark contrast to the severe and lasting disability reported by the patients, the authors wrote.

"Longitudinal studies are needed to define the prognosis of neurocognitive symptoms in patients with long COVID-19 syndrome," the team concluded.