Here's a well-known thought experiment: A runaway train is on course to collide with and kill five people who are stuck at a crossing down the track. There is a railway point and you can pull a lever to reroute the train to a siding track, bypassing the people stuck at the crossing but killing two siding workers.

What would you do? What is the ethical thing to do? Why? What if one of the siding workers was related to you? What if the people stuck at the crossing were convicted murderers on their way to prison? What if the people on the crossing were not killed but permanently maimed?

Have a think about it before reading on.

Unless you answered that you did not accept the situation at face value -- like Star Trek's Captain Kirk and the Kobayashi Maru simulation -- or refused to choose, you will have made some judgments about the relative value of the choices on offer and perhaps the relative value of the lives at risk.

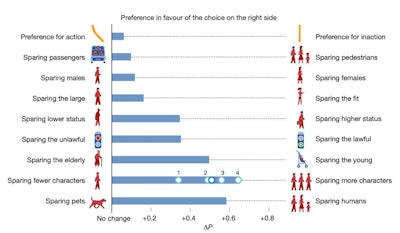

You are not alone in this: In a 2018 Nature paper, nearly 40 million people from 233 countries were prepared to make similar choices. On average, there were preferences to save the young over the old, the many over the few, and the lawful over the unlawful, though with some interesting regional and cultural variations.

Preferences of 40 million respondents for sparing people and things in a thought experiment about self-driving cars. See linked 2018 Nature paper for full details.

Preferences of 40 million respondents for sparing people and things in a thought experiment about self-driving cars. See linked 2018 Nature paper for full details.The need for value judgments

Making value judgments about people in a thought experiment is one thing, but making them in the real world with impacts on real people and their lives is another.

Ascribing value to a person's life has grim historical and moral connotations. If someone is deemed somehow less valuable than someone else, there is a risk that this is used to justify stigmatization, discrimination, persecution, and even genocide. We therefore need to be extremely careful about the moral context in which such judgments are made and the language we use to discuss them. Human rights, justice, and the fundamental equivalence of the life and interests of different people must be central.

Decisions that affect the health, livelihoods, and welfare of citizens are -- and need to be -- made all the time. In some cases, decisions affect length or quality of life, or liberty. Decision-making during the pandemic -- whether locking down, opening up, isolation, mask-wearing, or travel restriction -- is a potent recent example. Few people would argue that no decisions were necessary even if they may disagree with the details of some (or all) of the actual decisions made.

But if everyone's life and interests are equivalent, how do we avoid becoming paralyzed when faced with choices which inevitably will have (sometimes significant) consequences for different individuals?

We do this by understanding that the values we ascribe to the people affected by a decision are not absolute measures of their worth but merely tokens that allow us to undertake some accounting. If the process by which we allocate these tokens is transparent, just, and humane, then their use to inform a decision is morally defensible. Choosing to switch the points because this results in the least-worst outcome on average is morally very different from choosing to switch them because you have a seething hatred toward railway engineers.

How useful are QALYs?

There have been attempts to provide a quantitative framework for measuring health. The most commonly recognized token of health is the quality-adjusted life year (QALY), though there are others such as disability-adjusted life years (DALY).

One QALY is a year lived in full health. A year lived in less than full health results in less than one QALY, as does less than one year lived in full health. How much we scale a QALY for less than full health is determined by studies asking members of the public to imagine themselves ill or disabled and then enquiring (for example) how much length of life they'd trade to be restored to full health (time trade-off) or what risk of death they'd accept for a hazardous cure (standard gamble).

The QALY is a crude and clumsy tool. In a 2018 JAMA article, Neumann and Cohen criticized QALYs for relying on functional descriptions of health states (like pain, mobility, and self-care) rather than manifestations of human thriving (stability, attachment, autonomy, enjoyment).

Other critics claim QALYs are systematically biased against the elderly or the disabled, and they fail to take into account that health gains to the already healthy may be valued less than health gains to the already unhealthy (prospect theory). The scalar quantities contributing to a QALY ("utilities") reflect the perceptions of those surveyed during QALY development, validation, and revalidation. These perceptions may be clouded by fear or ignorance and may have little relation to the real experiences of people living with a health impairment or handicap. Some have argued that QALYs have poor internal validity and are therefore a spurious measure.

These are important, though arguable, technical criticisms, and to some extent, they explain the marked international variation in the use of the QALY. They are used in the U.K. (by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) and some Commonwealth countries but have been rejected as a basis for health technology assessment in the U.S. and Germany. And yet, decisions need to be made. If not QALYs, then what else?

The most emotionally charged criticism of QALYs is that they somehow inherently rank people's value according to how healthy they are or that the health of people who gain fewer QALYs from an intervention is somehow worth less than the health of those who gain more. This is a misunderstanding. QALYs (like the assessments you made of the lives at risk from the runaway train) are accounting tokens. When fairly, justly, and transparently allocated (and technical criticisms might be important here) they merely allow a quantitative assessment of outcome.

The rationale underlying QALY assessment is explicit that the value of a QALY is the same no matter who it accrues to: There is no moral component in the calculation. And nor is there the requirement that efficiency of QALY allocation be the sole (or even most important) driver of decision-making.

A QALY calculation is fundamentally contingent on the interaction of the intervention with the people being intervened on. Someone's capacity to benefit (which is what QALYs measure) depends not just on their characteristics but also on those of the intervention. Absolute ranking of QALYs as an empirical assessment of someone's "value" based on their health is therefore meaningless: A different intervention on the same set of people can result in a totally different estimate of outcome.

Dr. Chris Hammond from Leeds, U.K.

Dr. Chris Hammond from Leeds, U.K.Consider if rather than five people on the crossing, there was only one (and still two siding workers). A pure utilitarian consequentialist would switch from plowing the train into the siding to smashing it into the crossing. But this doesn't mean she has suddenly changed her mind about the value of the lives of the people involved, merely that the situation, and therefore the most efficient outcome, has changed.

QALYs don't ascribe a value to someone's life. They are accounting tokens, providing a (perhaps flawed) quantitative estimate of health outcome in a specific circumstance -- usually that of evaluation of an intervention relative to an alternative in an identifiable group of people. This is not to say that some people might not be harmed by a decision based on a QALY assessment, but that in and of itself does not make the decision unfair or unjust.

Alongside utilitarian efficiency and QALYs, egalitarian considerations of fairness and equity, distributional factors, affordability, and political priorities may (and often do) feed into the decisions that are ultimately made.

Dr. Chris Hammond is a consultant vascular radiologist and clinical lead for interventional radiology at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, U.K.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.