Have you ever wondered what it would be like to hear a mummy speak? It's now possible thanks to the magic of CT and 3D printing technology, which has enabled the re-creation of the distinct voice of an ancient Egyptian who's been dead for centuries. The process is detailed in a 23 January article in Scientific Reports.

A team of archaeologists, engineers, and medical physicists from the U.K. and Germany used CT to measure the precise dimensions of the vocal tract of the 3,000-year-old mummified body of Nesyamun, an Egyptian priest. They used these data to generate a 3D-printed model of the mummy's vocal tract and then attached the model to an electronic larynx. The procedure allowed them to replicate the unique sound and tone of the late Nesyamun's voice.

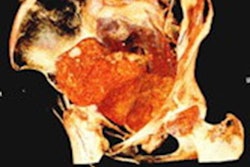

The mummified body of Nesyamun being prepared for a CT scan at Leeds General Infirmary in the U.K. All images courtesy of Howard et al and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

The mummified body of Nesyamun being prepared for a CT scan at Leeds General Infirmary in the U.K. All images courtesy of Howard et al and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0."This innovative interdisciplinary collaboration has produced the unique opportunity to hear the vocal tract output of someone long dead by virtue of their soft-tissue preservation and new developments in technology, digital scanning, and 3D printing," wrote the authors, led by David Howard, PhD, from the University of London.

Voice of the mummy

In prior work, Howard and colleagues developed a way to produce 3D-printed models of the vocal tracts of living individuals and use the models to simulate their voices. For the current study, they expanded upon this method to be able to synthesize the vocal sounds of the dead.

Their method could only work if the subject's relevant soft tissue in the vocal tract was reasonably intact. In the case of Nesyamun, x-ray images and CT scans performed on the mummy throughout the 20th century confirmed that the elaborate mummification process preserved the mandible and enough remaining components of the larynx and throat for an accurate re-creation of the vocal tract shape.

The researchers acquired new images of the entire mummy using a multidetector CT scanner, including an enhanced visualization of the vocal tract. Then they used open-source 3D medical image processing software (ITK-SNAP) to segment the CT scans and convert the data into a virtual 3D model. They also approximated positioning for portions of the soft palate and tongue that were missing from the mummy and added them to the 3D model.

After manual postprocessing, they used a 3D printer (Connex3 Objet260, Stratasys) to create a 3D-printed vocal tract, to which they attached an electronic larynx. The final apparatus was able to reproduce the frequency, loudness, vibrato rate, and depth of the mummy's voice as it pronounced simple, single-syllable words such as "bed" and "bad."

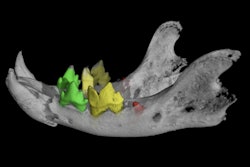

3D-printed vocal tract based on CT scans of Nesyamun's mummified body.

3D-printed vocal tract based on CT scans of Nesyamun's mummified body.Subsequent voice analysis showed that Nesyamun's sound output produced four sound format peaks that matched those of typical adult male speech extremely well, with loose variations attributed to individual differences.

To speak again

"While this approach has wide implications for heritage management/museum display, its relevance conforms exactly to the ancient Egyptians' fundamental belief that 'to speak the name of the dead is to make them live again,' " the authors wrote.

The Egyptian priest Nesyamun lived during the reign of Pharaoh Ramses XI, which began as far back as 1099 B.C. As a scribe and priest, Nesyamun's voice is presumed to have played a critical role in Egyptian society, with duties ranging from reading texts to chanting or singing the daily liturgy. His mummified body was first unwrapped in 1824 and is currently on display at Leeds City Museum.

Among the various hieroglyphic texts inscribed into Nesyamun's coffin include a qualification as being "true of voice" and a statement of his wish to be able to speak again after his death. Advancements in CT and 3D printing technology now make it possible for visitors of the museum to hear the transmission of sound from his actual vocal tract, emphasizing the mummy's humanity.

"Given Nesyamun's stated desire to have his voice heard in the afterlife in order to live forever, the fulfillment of his beliefs through the synthesis of his vocal function allows us to make direct contact with ancient Egypt by listening to a sound from a vocal tract that has not been heard for over 3,000 years, preserved through mummification and now restored through this new technique," the authors concluded.