A group of Italian researchers developed 3D-printed models of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract to provide important benefits to the surgical management of a patient with a compressed esophagus. The team has shared its clinical experiences in an online article posted by BMC Surgery.

The surgeons from the University of Siena recognized the need for advanced techniques to help them resolve a challenging case involving a 65-year-old woman with numerous GI complications, including ineffective peristalsis and Barrett's esophagus. Chest CT scans revealed that the patient had a compressed esophagus between a tortuous thoracic aorta and the left atrium. Thus, the group decided that the patient required antireflux surgery.

However, conventional imaging offered a limited view of the surgical area, insufficient for effective preoperative planning. As a result, the surgeons turned to 3D printing: They segmented the patient's CT scans, converted them into a virtual 3D model, and created a 3D-printed model containing the esophagus, thoracic aorta, upper stomach, and diaphragmatic crus (BMC Surg, 25 October 2019).

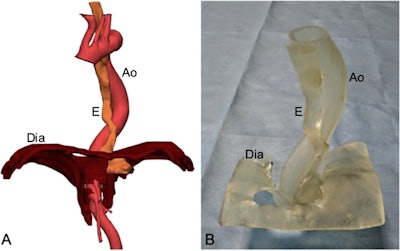

Left: Virtual 3D model of the distal esophagus (E), diaphragm (Dia), and aorta (Ao) based on CT scans. Right: 3D-printed model of the distal esophagus and its relationship with the mediastinal structures. Image courtesy of Marano et al. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Left: Virtual 3D model of the distal esophagus (E), diaphragm (Dia), and aorta (Ao) based on CT scans. Right: 3D-printed model of the distal esophagus and its relationship with the mediastinal structures. Image courtesy of Marano et al. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.A surgeon and computer engineer confirmed the accuracy of the virtual model before generating the final 3D-printed model, which took 48 hours and cost 230 euros to complete.

The resulting life-size 3D-printed model displayed the general position of the esophagus and tortuous thoracic aorta and also their interspatial relationships with surrounding anatomical structures. By referring to the model during preoperative planning, the surgical team was able to obtain precise measurements of distinct structures and the distances between them.

"This model enabled surgeons to verify the position of critical structures and to discuss all possible approaches and strategies to operate as well as plan all possible critical maneuvers," lead author Dr. Luigi Marano, PhD, and colleagues wrote.

The patient-centered approach to preoperative planning convinced the surgical team to proceed with robotic-assisted surgery, instead of the more common method of open laparoscopy, according to Marano and colleagues. They also noted that the 3D-printed model led to better evaluation of the target anatomy and more engaging preoperative discussions than planning with conventional imaging.

Furthermore, the surgeons consulted the 3D-printed model during the actual operation and reported that it was "fundamental to the safe outcome of the procedure."

"In this way, a real model in the surgeon's hands overcame the absence of tactile feedback of the robotic technology and the limitations of 3D CT images manipulation on the screen," the group wrote. Using the 3D-printed model for preoperative intervention planning and simulation, as well as intraoperative navigational guidance, "allowed the surgeon to focus on other key points, resulting in a safer surgery."

The team's preliminary clinical report demonstrates the feasibility, utility, and potential clinical benefits of using technological innovations such as 3D printing and robotic surgery to manage complex GI cases, an unimaginable feat until very recently, they concluded.