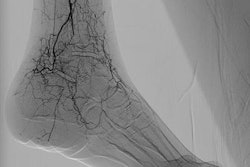

Research from the U.K. and the United Arab Emirates suggests that the effort to produce "prettier" x-ray images can lead to "collimation creep" as radiographers crop digital radiography (DR) images rather than use more appropriate collimation settings. The article was published in the June edition of the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences.

After observing U.K. radiographers at work, the multicenter research team found that many radiographers were using the cropping feature available with DR software to adjust images after they were exposed to make them look better, rather than positioning patients properly within the x-ray beam and using correct collimation settings (JMIRS, Vol. 50:2, pp. 234-242).

The practice could be leading to an increase in radiation dose levels over time, a phenomenon dubbed "collimation creep," according to first author Christopher Hayre, PhD, of the Institute of Applied Technology in Abu Dhabi, and colleagues.

"The cropping feature enhances the aesthetic appearance of 'a typical x-ray image,' with little attention to increases in ionizing radiation," wrote Hayre et al. "Findings presented here also highlight the possibility for 'collimation creep' whereby radiographers are tempted to increase collimation within the x-ray room, as it can be cropped postexposure."

Unintended consequences of going digital

The expanding use of DR has mostly been a boon for classical radiography. Digital x-ray images can now be easily viewed on workstations, archived digitally, and transmitted to remote locations. Digital x-ray also enables the use of advanced applications such as computer-aided detection and artificial intelligence to analyze digital data.

But going digital has also had unintended consequences for hospitals and imaging centers. In particular, going digital can result in subtle behavioral changes on the part of radiologic technologists (RTs) and radiographers who perform digital x-ray studies -- changes that in some cases can lead to "dose creep," in which radiation levels slowly increase over time as RTs and radiographers try to produce better image quality.

In the new paper, Hayre and colleagues examine two related phenomena: collimation creep and the growing use of digital side markers (DSMs), which are markers indicating the side of the patient that are placed on digital images after they've been acquired, rather than the anatomical side markers (ASMs) used traditionally. DSMs are more prone to error if digital images are accidentally flipped after acquisition.

To get a better handle on radiographer practice, the researchers stationed observers within DR suites at two National Health Service (NHS) trust hospitals in southeastern England to make note of how radiographers were performing their jobs. The observers recorded the use of image cropping as well as the placement of DSMs on images. After exams had been completed, radiographers were then asked about their practices, such as why they chose to crop images after exposure and why they used DSMs rather than ASMs. In all, 22 interviews were performed.

The observers noted frequent use of digital image cropping after acquisition, according to the research team, with some radiographers cropping as little as 1 cm and others cropping as much as 5 cm. When asked why in interviews, many radiographers said they resorted to cropping to produce images that were "neat" and "tidy," and in some cases to compensate for overcollimation.

The researchers postulated that the radiographers were trying to meet the ideal conception of an aesthetically pleasing x-ray image and that they were tempted to "open up" collimation during image acquisition and then crop down afterward -- a classic definition of collimation creep.

That said, a number of radiographers who were interviewed recognized the problems that image cropping can create, equating the technique with poor practice. One stated a preference to use "proper collimation" rather than image cropping, while another commented, "If you do your radiography well, you know your positioning, you do your collimation right -- why should you do the cropping?"

In the end, Hayre et al recommend that radiographers eschew concerns about producing attractive images and instead focus on the welfare of their patients by creating images that have proper collimation -- and thus lower radiation dose.

"It is important that radiographers utilizing the cropping feature postexposure ideologically disassociate themselves from their picture [radiograph] and remain mindful that patients are likely to be exposed to unnecessary levels of ionizing radiation if inappropriate collimation is practiced," the group wrote.

In their analysis of DSMs, the researchers found through their interviews that most radiographers see no difference between using digital and anatomical markers. The researchers believe this attitude could reflect a "lack of professionalism" among radiographers because it ignores the possibility that a digital image could be inadvertently flipped, leaving the marker on the wrong side of the patient.

That said, eliminating DSMs in favor of ASMs isn't totally practical. So instead, Hayre and colleagues propose that radiographers be made aware of the potential pitfalls of digital markers.

"The challenge, as identified, is limiting human error where possible and educating radiographers of the dangers," they concluded.