Add a mark to the win column for dog lovers: A recent Hungarian study using functional MRI (fMRI) found that man's best friend responds to both your words and how you say them. The results also help clarify how our ability to communicate may have evolved.

Researchers from Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest studied the responses of 13 dogs to different combinations of words and tone -- ranging from praise words delivered with a praising tone to meaningless words said neutrally. The group found that, like humans, dogs use the left hemisphere to process meaningful words and an area of the right hemisphere to distinguish intonation.

The dogs also appeared to integrate the two types of information: When praise words were delivered with a praising tone, their reward center was activated -- but only with this one combination, according to a report in the 2 September issue of Science (Vol. 353:6303, pp. 1,030-1,032).

One of the study participants, Barack, lies on the scanner bed. Photo by Enikő Kubinyi. All images and video courtesy of Attila Andics, PhD.

One of the study participants, Barack, lies on the scanner bed. Photo by Enikő Kubinyi. All images and video courtesy of Attila Andics, PhD.Though humans may have mastered words, the results suggest these neural mechanisms actually predate us.

This processing of words "does not appear to be a uniquely human capacity that follows from the emergence of language, but rather a more ancient function that can be exploited to link arbitrary sound sequences to meaning," noted lead author Attila Andics, PhD, a research fellow in the department of ethology, and colleagues.

Dogs vs. humans

Previous research has shown that humans use opposite hemispheres of the brain to process the intonation and meaning of words, or "lexical" items, with the added ability to combine the results, Andics explained in a release by the university.

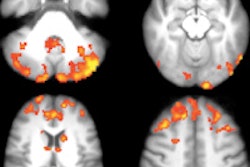

Video shows dog brain activation from human speech in the study. Yellow and red indicate auditory regions responsive to speech, while green represents reward center activity for praise words spoken with a praising intonation. Video by Anna Gábor created in MRIcron.

While other species have shown some ability in terms of using and understanding words, "nonhuman neural evidence for lexical processing is scarce," according to the authors. Comparing the process in dogs versus what has been observed in humans could help reveal how speech-processing mechanisms evolved, they wrote.

For the study, the researchers performed fMRI on 13 dogs, who were trained to remain motionless throughout the scans. To separate the effects of word meaning and tone, they used four types of communication:

- Praise words said with a praising tone

- Praise words said with a neutral tone

- Neutral words said with a praising tone

- Neutral words said with a neutral tone

The words were delivered using a recording of one trainer, with whom all of the dogs were equally familiar. fMRI was performed on a 3-tesla whole-body MRI system at the MR Research Centre at Semmelweis University in Budapest, with a Philips Healthcare Sense Flex medium coil and a single-shot gradient-echo planar sequence. The researchers also used standard T1-weighted 3D MRI with a turbo-field echo sequence for reference purposes.

The results showed a left-hemisphere response, or lateralization, only to the praise words, independent of the tone used. This suggests that "dog brains maintain intonation-independent lexical representations of meaning," the authors wrote. Meanwhile, when they looked at auditory brain regions, Andics and colleagues found that intonation affected the right middle ectosylvian gyrus, independent of word meaning.

Finally, the dogs showed greater activity in primary reward regions only when being praised both in meaning and tone. Specifically, a response was seen in the caudate nucleus and in the dopamine nuclei of the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra.

Barack receives praise after a successful scan. Photo by Enikő Kubinyi.

Barack receives praise after a successful scan. Photo by Enikő Kubinyi.Basically, if you're praising your dog, you want the intonation to match, Andics said. "So dogs not only tell what we say and how we say it, but they can also combine the two, for a correct interpretation of what those words really meant. Again, this is very similar to what human brains do."

Overall, the findings illustrate the comparable brain mechanisms between dogs and humans in speech processing -- and suggest we could share more with nonhumans than we might think.

"Our research sheds new light on the emergence of words during language evolution," Andics said. "What makes words uniquely human is not a special neural capacity, but our invention of using them."