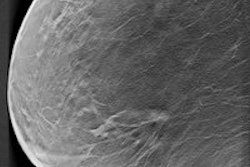

Researchers from Norway have found that organized mammography screening detected more early-stage cancers, with no change in advanced-stage cancers, calling into question the effectiveness of mass screening programs. But the study has drawn the ire of a screening advocate, who calls the findings a "biased guess."

The population-based open-cohort study estimated the effect of introducing a screening program in Norway on breast cancer stage distribution by comparing stage-specific incidence in women eligible for screening to the corresponding incidence prior to organized screening relative to the concurrent change in younger, ineligible women.

Mette Lousdal is from the department of public health at Aarhus University in Denmark.

Mette Lousdal is from the department of public health at Aarhus University in Denmark.What makes this study different than studies on cancer stage distribution is the use of birth cohorts rather than trends in mammography screening, self-reported data, or calendar time periods, wrote doctoral student Mette Lousdal from the department of public health at Aarhus University in Denmark (British Journal of Cancer, 2 February 2016).

Lousdal and her colleagues found that organized screening mammography resulted in more detected early-stage breast cancers, but no change in advanced-stage breast cancers.

"In this nationwide, population-based study with a refined exposure classification and long follow-up of birth cohorts of women previously invited to screening, we could not identify a decrease in the incidence of advanced cancers," they wrote. "Our conclusions depend on the plausibility of assuming similar developments over time in eligible and younger, ineligible women."

What screening is supposed to accomplish

Screening is expected to lead to an increase in incidence of early-stage cancers, which should then later be followed by a decrease in incidence of late-stage cancers. This is due to the fact screening advances the point of time when cancer is detected. The goal is that all cancers are intercepted in an earlier stage.

A crucial first step, then, in evaluating a screening program is to identify whether a downward shift the stage at which cancer is detected is accompanied by a decrease in incidence of advanced stages, according to the researchers.

They used birth cohorts rather than age groups to adequately control for lead-time bias and ensure that only women with an actual prior invitation to the screening program would be included when follow-up was extended to include the expected compensatory drop among women leaving the screening program.

They identified 49,883 women diagnosed with in situ or invasive breast cancer during the period of 1987-2011 and born between 1917 and 1980. They estimated relative incidence rate ratios comparing the development in the screening versus historic group to the younger versus younger historic group.

Women eligible for screening experienced a 68% higher increase in localized early-stage cancers than younger women, while the increase in incidence of advanced cancers (stage III and IV) was similar. Excluding the prevalence round, eligible women experienced a 60% higher increase in early-stage cancers, while the increase in incidence of advanced cancers remained similar.

"Even when we include the compensatory drop or exclude prevalence rounds, the increase in localized cancers persists," the authors wrote. "Unlike previous studies, we do not find a modest decrease in advanced cancers."

The researchers attempted to adjust for the lead-time effect by employing methods derived from studies on total incidence. One method is to include the compensatory drop, as one would expect fewer advanced cancers in older women previously eligible for screening at the expense of more localized cancers in women eligible for screening.

"However, when we focused on the stage-specific compensatory drop, this was more pronounced for stages I and II," they wrote. "This suggests that our understanding of how screening shift stages may need to be reconsidered, possibly owing to substantial heterogeneity in lead time."

Strengths and weaknesses

The main strengths of the study are the follow-up of an entire female population, the high-quality data from the Cancer Registry of Norway with 99.95% complete information on breast cancer incidence, and the population perspective that considers invitation -- and not attendance -- as exposure, according to Lousdal and colleagues.

"We have chosen a population perspective in our study, which means that we compare women invited to screening (regardless of whether they actually participated) with noninvited women," Lousdal wrote in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com. "This means that some of the cases of late-stage cancers will stem from women that never participated in mammography screening. We chose this perspective because it shows how screening works in a real-world setting with noncompliance. Comparing participants with nonparticipants will give a biased estimate, because the two groups have a different baseline risk of breast cancer."

The main limitation of their study is the missing information on stage (13% of all tumors) and tumor size (23%) that potentially could introduce selection bias if related to outcome and exposure. But when the researchers used a method to predict missing information and repeated the analysis, the results did not change.

Tabár weighs in

Screening advocate Dr. László Tabár from Falun University Hospital in Sweden zeroed in on the limitations of the study.

Dr. László Tabár is from Falun University Hospital in Sweden.

Dr. László Tabár is from Falun University Hospital in Sweden."History repeats itself: The authors of this article have joined the group of authors who question the positive impact of early detection on advanced cancer rate by repeating the same mistake that we have critiqued so many times; the Danish and Norwegian authors, just like all the other antiscreening authors, lack precise knowledge about each tumor's detection mode," Tabár wrote in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com. "They could not distinguish among cancers detected in women who attended screening (screen detected plus interval cases) and cancers that were detected outside screening."

It is certain the majority of the early-stage breast cancers in the study were detected among women who attended screening, he added, and is likely the majority of the advanced-stage breast cancers were patient- and physician-detected outside screening.

"Thus, making claims that modern mammography screening has little or no effect in decreasing the advanced cancer rate is simply a biased guess," he said. "It should be noted that the authors, just like the other authors they refer to ... are using registry data and no direct patient measures, still, all of them made claims that 'screening' does not result in decrease of advanced cancer."

The situation is a little more nuanced than that, Lousdal and colleagues clarified. The group is not advocating any extreme measures such as dismantling mammography screening, but rather a tweaking of the existing model.

"Our study indicates that we need to investigate differences in tumor growth in greater detail," she stated. "Some cancers are very aggressive and others are indolent. Some cancers grow from an early stage to a late stage in months and others take years. As an inherent feature, screening is more capable of detecting the indolent, low-risk cancers. Right now, the approach to mammography screening is 'one size fits all' where all women are screened in the same way. We need biomarkers to differentiate between high- and low-risk cancers. This would enable tailored screening according to tumor aggressiveness."

For future research, Lousdal's group plans to investigate differences in tumor growth.

"[T]his is intrinsically connected with how screening advances the time of diagnosis," she wrote. "This might lead to a better understanding of how screening shifts the stage distribution. Moreover, future research should investigate stage-specific mortality reductions to get a more complete picture of the overall benefits and harms of screening."

Tabár doesn't advocate any future research on this topic unless the study methodology is changed.

"How many more articles will be published without access to accurate data on detection mode?" he wrote. "This type of poor research has been a recurring theme during the past decade which harms women and confuses their physicians."