Today, CT is vital for assessing intra-abdominal and pelvic hemorrhage, and it has boosted trauma management and had major implications for radiologists, according to new research presented at the 2015 congress of the European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology (ESSR).

"CT has become a cornerstone of diagnosis in patients suffering from acute intra-abdominal hemorrhage following abdominopelvic trauma," noted Dr. James Hallinan, associate consultant in the Department of Diagnostic Imaging at National University Hospital (NUH) in Singapore. "Multidetector CT [MDCT] allows for rapid acquisitions, multiplanar reconstructions, and multiphasic acquisitions. Accurate depiction of the site of hemorrhage allows for the right therapeutic decision to be made."

In the appropriate clinical setting, a negative CT can reduce unnecessary invasive procedures from being performed. In turn, detection of active contrast extravasation allows for consideration of further digital subtraction angiography (DSA) with embolization and/or operative management, he explained.

Along with co-author Dr. Eide Sterling, also from the NUH, Hallinan has sought to evaluate the role of CT in the diagnosis of acute hemorrhage in abdominopelvic trauma, highlight the use of multiphasic acquisitions to characterize contrast extravasation and vascular injuries, compare CT and digital subtraction angiography in the diagnosis of acute hemorrhage in abdominopelvic trauma, and investigate the type of injuries faced by on-call radiologists in the emergency department.

MDCT can detect bleeding rates of greater than or equal to 0.3 ml/min, while DSA, another useful method for evaluating active hemorrhage in the trauma setting, can only detect bleeding rates of 0.5 ml/min.

"CT is readily available in most emergency departments or at least within easy reach," they stated in an ESSR e-poster. "It is also relatively straightforward to perform and the information is available to the radiologist and clinicians at the time of scanning, allowing rapid decision-making."

Recommended protocol

No standard CT trauma protocol exists, but several studies have focused on the use of multiphasic acquisitions in addition to a portal venous (PV) phase for more accurate diagnosis, and there is a trend toward triphasic studies utilizing arterial, PV, and delayed phases, which is reflected in guidance from the U.K. Royal College of Radiologists (RCR), they explained.

The RCR advises that hemodynamically unstable patients with a high risk of vascular injury should undergo a triphasic CT protocol. This is aimed at increasing the sensitivity for detection of life-threatening hemorrhage and for treatment planning, e.g., characterizing arterial injuries and arterial versus venous hemorrhage.

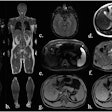

At the NUH, a triphasic contrast-enhanced technique on a 64-detector row unit is used for detection of active hemorrhage in patients with blunt abdominal and pelvic trauma. Coverage includes the highest part of the diaphragm to the greater trochanters in all phases, and a section thickness of 0.625 mm and reconstructed slice thickness of 3 mm are used.

All patients receive a single bolus of 100 mL of nonionic iodinated contrast injected at a rate of 3 mL/sec using a dual-syringe power injector. Scanning delays from the time of injection are 25 sec for the arterial phase, 70 sec for the PV phase, and five minutes for delayed phase CT. Parameters for the delayed phase are identical to those for the PV phase, and oral contrast is not administered.

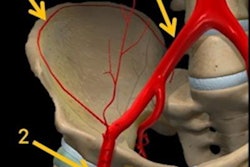

"CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis with multiphasic acquisitions can reliably depict various vascular injuries and allows for differentiation of arterial from venous hemorrhage," Hallinan and Sterling wrote. "Vascular injuries that may be seen include active arterial and venous extravasation, pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistula, and arterial dissection. In most major trauma centers, DSA is increasingly reserved for confirmation and guiding therapy for these injuries."

Why is an arterial phase useful?

Active extravasation of hemorrhage on single portal venous phase studies is of limited sensitivity and specificity, they continued. An arterial phase can improve sensitivity for the detection of active hemorrhage, and these are key factors:

- Abdominal and pelvic arteries are optimally opacified with increased accuracy at detecting the site of hemorrhage

- Characterize arterial versus venous hemorrhage

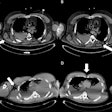

- Arterial hemorrhage identified on the arterial phase and enlarges on the subsequent phases

- Venous hemorrhage may only be visualized on the portal venous phase, and differentiation is useful for management

- Venous injuries typically do not require DSA and may require operative management, e.g., pelvic stabilization

- Arterial hemorrhage usually requires DSA and embolization

- Useful in the assessment of other vascular injuries including arterial dissection, occlusion, and pseudoaneurysms

- Comparing arterial, portal venous, and delayed phases allows for qualitative assessment of the rate of hemorrhage and injury severity

- Postprocessing techniques (e.g., maximum intensity projections) can produce high-resolution arteriograms, which are useful for treatment planning by the interventionalist

Pelvic CT angiography has been shown to be an important advancement in the evaluation of patients with blunt pelvic trauma, and while the role CT angiography in abdominal trauma is still being evaluated, it is likely to be useful in splenic and hepatic injuries.

Delayed phase studies can be performed following the arterial and portal venous phases. Improved visualization of active extravasation, which will enlarge between phases, can result and these studies can provide qualitative assessment of the rate of hemorrhage and more accurate characterization of arterial injuries, i.e., differentiation of pseudoaneuryms from extravasation. Urinary extravasation may also be detected on the delayed phase. A plain, unenhanced phase is not routinely used in trauma protocols, the authors added.

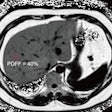

Images are evaluated primarily for evidence of active extravasation of contrast. In addition, areas of active hemorrhage are expected to increase in size and remain of higher attenuation than the aorta on the portal venous and delayed phase images, they wrote.

Multiphasic sequences offer increased information, but at an increased radiation dose. At NUH, this has been tackled by reduced dose delayed phase images, which aim to characterize injuries detected on the higher resolution arterial and portal venous phases. Low dose early (angiographic phase) exams also can be used.

Vascular injuries were historically assessed using DSA. Initial studies of CT in the 1990s used single detector systems with long acquisition times, which typically were limited to single portal venous phase studies. Improvements in CT have facilitated the implementation of MDCT, which has mainly replaced DSA in the initial evaluation of patients with acute trauma. CT angiograms of the head and neck, thorax, abdomen, pelvis, and extremities have become commonplace in busy trauma centers, the authors pointed out.