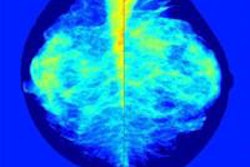

It's well-known that mammography is less effective in women with dense breast tissue, and that women with dense tissue have a three- to sixfold higher breast cancer risk than those with entirely fatty tissue. But what has not been established is which supplemental modality is best for these women.

Dutch researchers plan to remedy that by investigating the use of MRI in addition to mammography in a multicenter, randomized controlled trial that will be conducted through the Netherlands' biennial breast cancer screening program, according to a paper published in Radiology.

The Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening (DENSE) trial is intended to explore the effectiveness and cost of screening women ages 50 to 74 who have dense breast tissue, using mammography and MR compared with mammography alone. The trial will be supported by Bayer HealthCare's Medical Care division (Radiology, June 23, 2015).

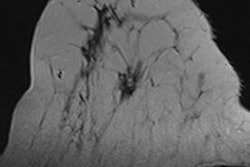

"MR imaging has the potential to improve breast cancer detection at an early stage because of its higher sensitivity," wrote a group led by Dr. Marleen Emaus of University Medical Center Utrecht. "However, MR imaging is more expensive and is expected to be accompanied by an increase in the number of false-positive results and, possibly, an increase in overdiagnosis."

All subjects in the study will have extremely dense breast tissue (BI-RADS breast density category 4) and negative mammography results. The participants are divided into two groups: 7,237 will undergo MRI in addition to mammography for three screening rounds, and 28,948 will be treated according to the Dutch breast cancer screening program's current practice -- that is, no further screening until the next mammography exam two years later. The researchers plan to use Matakina Technology's Volpara software to assess breast tissue density.

"The software has been installed on servers in the screening units of the Dutch screening program, all of which are equipped with digital mammography systems of the same brand," the authors wrote. "The software fully automatically estimates breast density volumes from raw full-field digital mammography data."

The study's primary measure is whether there will be a reduction in interval cancers as a result of additional cancers detected on screening breast MR, Emaus and colleagues wrote. Secondary outcomes will include the number of cancers detected on MR screening, the proportion of false positives, the diagnostic yield of breast MR, tumor characteristics (especially tumor size), and cost-effectiveness. The researchers will administer a questionnaire that addresses each participant's health status and breast cancer risk at the time she is recruited; follow-up questionnaires will be given each year.

The trial's first participants were randomized in December 2011. Emaus' group expects study enrollment to be completed this year and the first results to be presented in 2016.

Although the trial is aimed at women 50 and older, it may give some insight into whether women younger than 50 with dense tissue would be served by having MR as an adjunct to mammography screening, according to the researchers. And it's important to answer this question soon.

"At this point in time, it is too early to advocate implementation of expensive supplementary MR imaging in the general breast cancer screening population with extremely dense breasts because effectiveness, in terms of mortality reduction and quality-adjusted life years gained, has not been examined in randomized controlled trials," the group wrote. "The time to act is now, before breast density legislation (such as that in the United States) induces a worldwide increase in supplementary testing that, once in place, cannot be properly evaluated and will be very difficult to reverse."

Study disclosures

Co-author Nico Karssemeijer, PhD, is shareholder in Matakina Technology, and Dr. Ritse Mann, PhD, serves as a speaker for Bayer HealthCare.