In 2010, the German Radiological Society (Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft, DRG) commissioned Gabriele Moser, PhD, an eminent medical historian, to research the organization's role between 1933 and 1945. The results will be presented in an exhibition at the 95th German Radiology Congress and seventh Joint Congress of the DRG and its Austrian counterpart, the ÖRG, to be held in Hamburg, Germany, in May. This month, the radiology journal RöFo is due to begin a five-part series on various aspects of radiology and medicine during the Nazi period.

RöFo: We know a great deal about the role of medicine and the medical professions during the Third Reich. Did different professions vary in their attitudes to the Nazi state, or were they all equally guilty?

Gabriele Moser, PhD, medical historian. Copyright Gabriele Moser.

Gabriele Moser, PhD, medical historian. Copyright Gabriele Moser.

Moser: The criminal aspect is still a core area of historic research on the role of medicine during the Nazi era. Hundreds of thousands of people were forcibly sterilized, and tens of thousands died after being infected with diseases or subjected to medical experiments in concentration camps and elsewhere. Almost every medical profession was involved, but the main focuses of research have been the experiments carried out by surgeons in Ravensbrück; typhus vaccine trials by bacteriologists and virologists at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen; and aviation medicine experiments by specialists in physiology and internal medicine at Dachau.

One important figure was the Munich radiologist Dr. Georg August Weltz, who was tried and acquitted at the Nuremberg doctors' trials. He joined the advisory board of the DRG in 1936, and chaired the first Greater German Radiology Conference in 1938. As head of the Institute of Aviation Medicine in Munich, he had overall scientific responsibility for the often fatal experiments carried out by Dr. Sigmund Rascher in Dachau in 1942.

One area that has received less attention is that of everyday medical practice during this period. This includes the implementation of the Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses, or law on the prevention of genetically diseased offspring, which was effectively the racial constitution of National Socialism. Surgeons and gynecologists bore the main responsibility for enforcing it, but in 1936 radiographers and radiologists began engaging in another unethical practice: forced sterilization on the grounds of "racial hygiene."

What was the role of the various medical associations during the Nazi era?

Because relatively little attention has been given to everyday medical practice during this period, we knew little about the associations' role in Nazi scientific research. The first specialist conference on this area, held at the beginning of October 2013, sought to outline an initial strategy concerning research in this field. Like other professional associations, the DRG played a key role in determining the working conditions of its members, even under Nazi rule. The Nazi party believed it was important to secure the cooperation of the medical professions because the survival of the Nazi state relied on them to provide public healthcare.

In 1934, there were plans to combine the associations into a single representative body that also advised the government, and we know from documents concerning these plans that party membership was not a precondition for holding senior posts in the DRG. Dr. Karl Frik, the head of the organization until 1939, had no party affiliations. His successor, Dr. Werner Knothe, joined the Nazi party in 1941; Knothe's deputy, Dr. Carl Hermann Lasch, was a member, and 11 of the 16 advisory committee members also belonged. According to reliable research, at least 45% of the physicians registered with the Reichsärztekammer between 1936 and 1945 were members.

The DRG was not just a medical and scientific society -- it acted as a legally independent consultative body on political and social issues. It was consulted on issues such as the appropriateness of mass x-ray screening for tuberculosis, and the fees payable for x-ray and radium sterilization. Membership of the association also provided an opportunity to discuss issues with fellow medical specialists; in the case of the DRG, these included colleagues who had been driven out of Nazi Germany, such as Dr. Friedrich Dessauer.

How important were radiology and radiotherapy to the Nazis?

The autumn 1938 version of the DRG's charter stated that its role included compiling and evaluating scientific research, and "advising and assisting the Reichsärztekammer on the use of x-ray and radiation research for the benefit of public health." This assistance related not only to diagnosis and therapy in hospitals and independent practice, but to "mass screening carried out for public health purposes, and the prevention of injury in eugenics."

We have already mentioned the use of sterilization to prevent genetic disease and maintain "racial hygiene," but radiology had another important role. Preventing tuberculosis was a major focus of Nazi health policy because the disease had lasting effects on its victims and required expensive treatment over long periods. A central register of x-ray screenings to improve the health of the "Volkskörper" had been under consideration since the 1920s, but the mass screening of the local population in occupied Poland and the Soviet Union from 1939 onward was part of a much larger project.

In 1939, Prof. Hans Holfelder established the SS-Röntgensturmbann, or x-ray battalion, the aim of which was to identify tuberculosis patients who presented a risk of infection to the Wehrmacht's soldiers and German settlers, and "render them harmless." A variety of proposals were made, ranging from resettling the victims in isolated reservations to having them summarily shot by SS Einsatzkommandos, but research has so far failed to clarify which of these, if any, were implemented.

What sources have you used in your work?

There is no archive material from the DRG during the Nazi period and the documents in the Deutsches Röntgen Museum begin after the World War II, but some DRG membership lists that emerged as part of a bequest provide a picture of its membership structure during the Nazi period. A list produced in December 1938, after Jewish medical professionals had their licenses withdrawn on 30 September, reveals that 159 names have disappeared from the previous list, which shows 1,296 members. These names were compared with the Reichsarztregister, which lists all medical professionals in the Third Reich, and used to produce a memorial list. Around 12.3% of the DRG's members were expelled for racial reasons.

I also used contemporary sources such as scientific journals, textbooks and other specialist publications, records from various ministries and universities held in government archives, and personnel files. The example of Dr. Hermann Holthusen of Hamburg sheds interesting light on everyday life for medical professionals during the Nazi era and on how they communicated with their international colleagues.

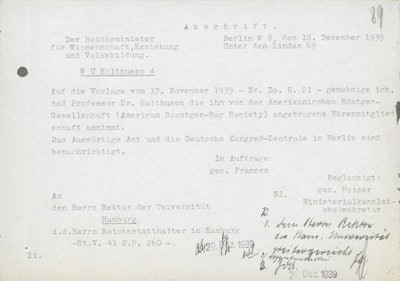

Letter from the Reich minister of science and education allowing Dr. Holthusen to accept honorary membership into the American Roentgen Ray Society, 1939. Source: Staatsarchiv Hamburg, 361-6: Hochschulwesen Dozenten- und Personalakten. IV 1307: Prof. Dr. med., Dr. h.c. Dr. h.c. Hermann Holthusen.

Letter from the Reich minister of science and education allowing Dr. Holthusen to accept honorary membership into the American Roentgen Ray Society, 1939. Source: Staatsarchiv Hamburg, 361-6: Hochschulwesen Dozenten- und Personalakten. IV 1307: Prof. Dr. med., Dr. h.c. Dr. h.c. Hermann Holthusen.We also have witness statements by the victims of the Auschwitz experiments that involved using x-rays in castration. The survivors' perspectives have become an important focus of historical research over recent years; as well as helping to restore their identities, they can be seen as an attempt to restore the balance so that the emphasis is not always on the perpetrators. Some of the victims were themselves medically trained, and they represent an important new source of information that needs to be documented.

What can visitors to the exhibition (to be held in Hamburg in May) expect?

The exhibition is based on a series of articles produced as part of a research project on radiology under the Nazis. After the recent publication of a book on the scientific and technological development of radiology, to mark the DRG's 100th anniversary, the event seeks to remedy some of the blind spots in the organization's history.

The historian Thomas Stamm-Kuhlmann wrote a paper on Peenemünde, a place of untold misery where V2 rockets were made using slave labor. Its title was a trenchant summary of the dilemma we face as historians: Der Glanz der Technik und der Schatten der Erinnerung (The Brilliance of Technology and the Shadow of Remembrance).

The media to be used in the exhibition will also include portrait photographs, biographical documents, illustrated archive material, audio sources from the German radio archive, films, and other important documents illustrating the historical framework in which radiologists researched, taught, and practiced under the Nazis. All of these will be on display at the German Radiology Congress in 2014.

Editor's note: This article is an edited version of a translation of an interview carried out in German and published online by the DRG. Translation by Syntacta Translation & Interpreting.

Copyright 2014 Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft e.V.