German researchers have shaved more than a half hour off the normal time it takes to respond to urgent calls for stroke care by equipping an ambulance with a CT scanner and other state-of-the-art diagnostic and communications equipment, which transmits patients' vital information to the hospital before the patient arrives.

The mobile setup was built for efficiency. Following an emergency call notifying accident and emergency staff of a patient with stroke symptoms, the research team ordered patient care from the mobile stroke unit (MSU) -- or from a conventional hospital-based stroke care unit, alternating the point of care on a weekly basis.

By beginning stroke assessment at the moment of patient contact on site, they reduced the median time from alarm to treatment decision from 76 minutes to 35 minutes -- an eternity in stroke care, where "time is brain" -- and a facility's ability to rapidly treat appropriate ischemic stroke patients with thrombolysis is vital in saving brain function, as well as lives.

As critical as rapid assessment and the initiation of recanalization therapy is for ischemic stroke patients, it is "difficult to achieve in clinical practice because neurological examination, imaging, and laboratory analysis are needed so that hemorrhagic stroke and other contraindications to thrombolysis can be excluded," explained Dr. Silke Walter, Dr. Panagiotis Kostopoulos, and colleagues from Saarland University Hospital, in Homburg, Germany, and colleagues from John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, U.K., as well as Nuremberg Hospital in Nuremberg, Germany. Immediate blood-pressure management is also important for preserving brain function (The Lancet Neuroradiology, 11 April 2012).

As a result, less than 15-40% of patients with acute stroke arrive at the hospital early enough to receive thrombolytic treatment and only 2-5% of patients actually receive it. Of those patients who do receive state-of-the-art stroke treatment, outcome is closely related to the time to treatment, they noted.

"Management of acute stroke must be reconfigured if we are to overcome the problem of patients arriving at the hospital too late for treatment," Walter et al wrote.

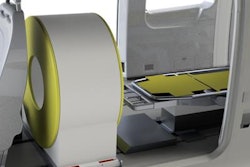

The Lancet study aimed to compare the time from the emergency call or alarm to the therapy decision between mobile stroke unit (MSU) and hospital intervention. Alternating care scenarios from week to week, patients received either prehospital stroke treatment in a specialized ambulance (the MSU was equipped with a CT scanner, point-of-care laboratory, and telemedicine connection) or optimized conventional hospital-based stroke treatment with a seven-day follow-up, which served as a control group.

MSU was to be compared to optimized hospital care, so the researchers included point-of-care laboratory testing at the centralized hospital laboratory to save time.

All patients were aged 18-80, and had had one or more stroke symptoms according to the modified recognition of stroke in the emergency room (ROSIER) scale, including facial paresis, paresis of arm or leg, aphasia, or dysarthria that had begun within the previous two to five hours. The MSU team, which included a paramedic, a stroke physician, and a neuroradiologist, obtained the patient's history; performed a neurological exam, CT scan, and laboratory examinations; and, if the patient was eligible, gave thrombolysis directly at the emergency site. The MSU program was integrated into the regular emergency management system in a mixed urban and rural setting.

Along with nonimaging equipment, the van used in the study was equipped with a lead-shielded Tomoscan M scanner (Philips Healthcare) or, in the last year of the study, a Ceretom (Neurologica) CT scanner, allowing multimodal imaging with CT angiography and CT perfusion. The telemedicine system (Myetec) enabled transmission of digital imaging and communication data via the universal mobile telecommunication system to the hospital PACS.

The primary endpoint was time from alarm (emergency call) to the therapy decision. Also tallied were the number of patients who received intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase, and time from alarm to intravenous thrombolysis. Further secondary endpoints were National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) cutoff values (≤1 or ≥8 points improvement), Barthel index (≥95 points), and mRS scores (≤2) at days one and seven for patients who had stroke.

The results showed that prehospital stroke treatment cut the median time delay from alarm to therapy decision substantially to 35 minutes from 76 for the control group (p < 0.001) -- a median difference of 41 minutes for each patient.

"We also detected similar gains regarding times from alarm to end of CT, and alarm to end of laboratory analysis, and to intravenous thrombolysis for eligible ischemic stroke patients, although there was no substantial difference in number of patients who received intravenous thrombolysis or in neurological outcome. Safety endpoints seemed similar across the groups," Walter and colleagues reported.

Comparison of decision times for pretreatment with optimized hospital care in ischemic stroke patients

|

Despite the speedier care, however, indicators of neurological outcome at days one and seven did not substantially differ between patient groups. Six patients (11%) in the MSU group and control patients (6%) experienced events that were tracked as safety endpoints of the study. Five patients (9%) in the MSU group and two patients (4%) in the control group died of stroke-related or neurological causes.

Three patients receiving thrombolysis and one of the untreated patients -- all four from the MSU group -- died. No nonfatal secondary intracranial hemorrhage was found, but there was a nonfatal cerebral herniation and edema in one control-group patient, and peripheral hemorrhage in one MSU patient.

"Our main findings are that the strategy of prehospital stroke diagnosis and treatment allows therapy decisions a median of 35 minutes after alarm in clinical reality. Median time from symptom onset to intravenous thrombolysis was 72 minutes, representing a new timescale in acute stroke management," the authors stated.

Most stroke patients still arrive at the hospital too late to receive necessary treatment, and the study showed that MSU stroke management is faster on average than hospital-based care scenarios. According to the generally accepted "time is brain" concept, such large reductions in treatment time should translate into improved outcomes, and recent studies bear this out, the group wrote. The findings of this study can be generalized to other countries with similar emergency-management healthcare systems in place.

Still, this study revealed no significant differences in treated patients or neurological outcomes. Besides the small sample size that limits its power to discern improvements with MSU, the study was unable to evaluate the potential effects of previous disability, or longer-term outcomes.

Larger studies are needed, but "the results of this first randomized trial of the MSU strategy of bringing the hospital to the patient with stroke show that guideline-adherent diagnosis and therapy can reliably be delivered within the first 35 minutes after alarm, thus speeding up acute stroke management," concluded Walter et al.