Evidence is growing that CT is better than x-ray or low-dose whole-body radiography exams at detecting ingested or internally concealed illegal drugs. It is rapid, more accurate, and may also be cost-effective, according to an article published online on 15 December in the European Journal of Radiology.

Diagnostic imaging is used to help identify drug smugglers who use their bodies to transport merchandise, and conventional radiography exams have been the standard procedure used for many years. However, it can be difficult for radiologists to detect small capsules on x-ray images.

Detection of drug containers is crucial to retain suspects. In Switzerland and other countries, the time that a suspected smuggler may be held in custody is limited to 24 hours without proof that it is likely the person has ingested drugs. Also, with the steady increase in intercepted drug suspects, the availability of special holding cells is getting taxed to capacity. For this reason alone, misapprehended individuals need to be released as rapidly as possible.

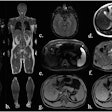

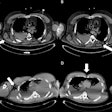

Top left: Axial plane in pulmonary window showing three pellets underneath the tongue. Top right: 3D reconstruction of an incidental finding of three sublingual cocaine pellets in a case of brawl/fist fight with subsequent CT and scan of the viscerocranium. The patient was immediately put under arrest and transferred to the affiliated custody ward. This scan was performed to rule out facial fractures sustained during the fist fight. Bottom left: Secured evidence of similar pellets (weight approximately 1 g). Bottom right: 3D reconstruction of gas-filled condom with two pouches (bags) of cocaine powder inside located in the descending colon. All images courtesy of Dr. Patricia Flach.

Top left: Axial plane in pulmonary window showing three pellets underneath the tongue. Top right: 3D reconstruction of an incidental finding of three sublingual cocaine pellets in a case of brawl/fist fight with subsequent CT and scan of the viscerocranium. The patient was immediately put under arrest and transferred to the affiliated custody ward. This scan was performed to rule out facial fractures sustained during the fist fight. Bottom left: Secured evidence of similar pellets (weight approximately 1 g). Bottom right: 3D reconstruction of gas-filled condom with two pouches (bags) of cocaine powder inside located in the descending colon. All images courtesy of Dr. Patricia Flach.To determine which diagnostic imaging procedures produce the best results, radiologists from Bern and Zurich compared the accuracy of different modalities in a retrospective study. They evaluated 35 CT exams, 70 digital radiography (DR) exams, and 30 low-dose linear slit digital radiography (LSDR, Lodox Systems) exams taken of 83 suspects between February 2004 and April 2011.

The suspects included 76 men and seven women, ranging in age from 16 to 45 years. Almost half underwent multiple exams. Two radiologists independently interpreted the exams, one a radiologist experienced in abdominal imaging, and the other a senior resident with focused training in forensic radiology. When their opinions differed, the radiologists reread the exam together to reach consensus. The gold standard for an inaccurately accused suspect was passage of three consecutive drug-free bowel movements.

Abdominal CT scans were overwhelmingly superior to the other modalities, with 100% sensitivity, 94.1% specificity, 94.7% positive predictive value (PPV), and 100% negative predictive value (NPV). This was true for imaging of all three types of suspects: "body packers," who swallow a large amount of packets for gastrointestinal tract passage; "body pushers," who hide drugs in bodily orifices; and "body stuffers," who ingest small amounts of loosely wrapped drug pellets if they suspect that are about to be intercepted.

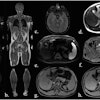

Top left: Low-dose linear slit digital radiography (LSDR) of a typical body packer with 145 intracorporal packs along the alimentary tract. Bottom left: Magnified view of the packs. Note the radiolucent rim within the periphery of the packs due to air trapping creating the so-called "double-condom sign" and "halo sign." Top right: DR of a typical body packer with 83 cocaine packs in the gastrointestinal tract. Bottom right: Note the longitudinal packs (weight approximately 10 to 12 g) projecting over the colon. The magnified view depicts the typical "double-condom sign" due to inevitable air trapped within the wrapping layers during manufacture.

Top left: Low-dose linear slit digital radiography (LSDR) of a typical body packer with 145 intracorporal packs along the alimentary tract. Bottom left: Magnified view of the packs. Note the radiolucent rim within the periphery of the packs due to air trapping creating the so-called "double-condom sign" and "halo sign." Top right: DR of a typical body packer with 83 cocaine packs in the gastrointestinal tract. Bottom right: Note the longitudinal packs (weight approximately 10 to 12 g) projecting over the colon. The magnified view depicts the typical "double-condom sign" due to inevitable air trapped within the wrapping layers during manufacture.DR and low-dose linear slit digital radiography exams were less accurate. CT exams had an overall accuracy rate of 97.1%, followed by DR (71.4%, and 60% for low-dose linear slit digital radiography).

There were a total of 54 drug carriers, or 65% of the total taken in custody. All who had CT exams were positively identified, a total of 23. However, one innocent person was misidentified.

Lead author Dr. Patricia Flach, of the Centre for Forensic Imaging at the University of Bern Institute of Forensic Medicine, and colleagues noted three concerns relating to CT examination: radiation dose, cost, and the undependability of density measurements.

Capsules holding cocaine are of different densities. It is important to perform window-level adjustments to detect drug containers, according to the authors. It also helps for a radiologist to know what the typical size and appearance are of different cocaine containers. With this knowledge, they can be better distinguished from normal intestinal gas, calcifications, scybala, and other foreign bodies.

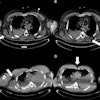

Left: LSDR of a typical body packer with a multitude of cocaine packs within the alimentary tract. Right: Same image with highlighted intestinal packs.

Left: LSDR of a typical body packer with a multitude of cocaine packs within the alimentary tract. Right: Same image with highlighted intestinal packs.The authors noted that it was also important for a radiology report to contain a precise description of the number of drug containers that are identified, and to indicate where they are located in the intestinal tract. This makes the job of the feces evaluators easier.

They also recommended that low-dose abdominal CT procedures be implemented to keep radiation exposure as low as possible. They noted, however, the accuracy of this procedure could eliminate the need for additional exams and additional radiation exposure. In this small group of suspects, 46% underwent multiple exams.

The higher cost of CT exams could be offset somewhat because additional exams would not be needed, and because individuals who were inappropriately apprehended could be released faster. This could save the costs incurred by keeping a suspect in custody overnight and for up to a week. A negative exam would also free space in a cell equipped with a special toilet for the next suspect.