Diagnosing and locating the source of brachial plexus impairment can be clinically challenging. An MRI examination may complement an assessment made with electromyography, but it is expensive, and how accurate and useful is it?

A retrospective study of 157 patients who had the examination at one of three hospitals in Italy determined that from a patient-by-patient perspective, the overall diagnostic accuracy of a brachial plexus MRI is relatively high. For patients suspected of having a space-occupying mass, accuracy is very high, according to an article-in-press published online on 7 November by the European Journal of Radiology.

The brachial plexus is a network of nerves that sends signals from the spinal cord located in the spinal canal of the vertebral column to shoulders, arms, and hands. Brachial plexopathy causes weakness, sensory loss, pain, and decreased movement in these regions. It may be due to inflammatory conditions caused by a virus or immune system problem, exposure to drugs, and/or side effects from chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment.

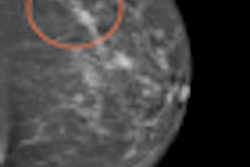

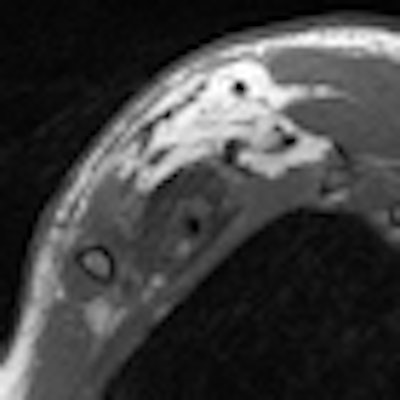

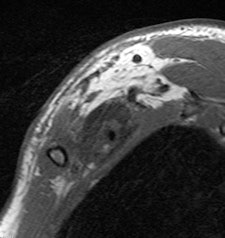

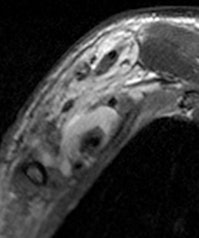

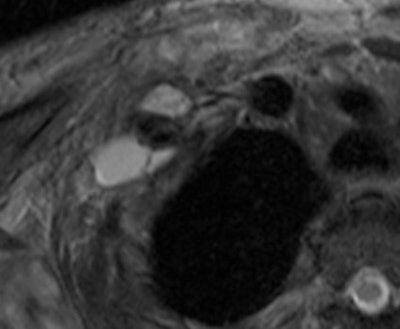

Young man who underwent a brachial plexus MRI examination following a motorcycle accident. A complex brachial plexus lesion is depicted. This case has been considered a true positive. All images courtesy of Dr. Alberto Tagliafico.

Young man who underwent a brachial plexus MRI examination following a motorcycle accident. A complex brachial plexus lesion is depicted. This case has been considered a true positive. All images courtesy of Dr. Alberto Tagliafico.

The objective of the Italian study was to evaluate the accuracy of brachial plexus MRI examinations performed in clinical settings on a balance of patients with early and advanced disease. The reference standard to determine accuracy of diagnosis with this exam was surgical findings and clinical follow-up with the patient at least 12 months later.

Images from 157 patients who had the examination between March 2006 and April 2011 at three hospital radiology departments, which performed at least 20 of these examinations each year, were independently reinterpreted by two experienced radiologists blinded to the patients' radiology reports and medical records. A third radiologist interpreted any examinations in which there was a difference of diagnosis or reporting of indeterminate findings.

Patients ranged in age from 18 to 84 years. Their lesions detected by MRI represented a mix, including 35 root avulsions and brachial plexus cord injuries, 22 primary or secondary tumors, and four each entrapment syndromes, fibrous scars, and Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

Lead author Dr. Alberto Tagliafico, of the department of experimental medicine of the University of Genoa's Institute of Anatomy, and colleagues defined an abnormality as being a true positive if the reported MRI findings and the reference standard matched. Abnormalities not identified by MRI were classified as false negatives.

The radiologists identified 42 true-positive abnormalities, nine false-positives, 10 false-negatives, and 96 true-negatives. The authors stated that they decided to assign a false negative if the reference standard recorded more lesions than those described in the MRI report.

Overall, the sensitivity for the total number of examinations analyzed on a per-patient basis was 81% and specificity was 91%. Analyzed by findings, mass lesions had the highest positive predictive value at 95%, followed by traumatic injury at 91%. The lowest was for entrapment syndromes, at 80% and 66% for post-treatment evaluation. Negative predictive values ranged from a low of 83% for traumatic injury to a high of 2% for mass lesions and post-treatment evaluations.

The low positive predictive value in the post-treatment group of patients confirmed that some of the positive results were false positives, and that this meant patients should either be selected more appropriately or biopsied to confirm the findings of any positive results, the authors wrote.

They also recommended that more research should be performed, including an assessment of a possible increase in diagnostic accuracy related to the introduction of diffusion-weighted sequences of exams. Identifying the pathological conditions in which brachial plexus MRI examinations would be more likely to give clinically useful information would be beneficial, and might have the outcome of reducing the number of these expensive studies when they would have a high probability of not yielding useful clinical findings, they stated.