Neuroscientist Christian Schwarzbauer, PhD, is using functional MRI (fMRI) as part of a new research initiative in Aberdeen, U.K., to answer one of the most heart-wrenching questions in clinical medicine: Does a spark of conscious life still shine in the minds of patients who are submerged in a persistent coma?

Published research suggests fMRI can reveal when comatose patients show a spark. A decade ago, collaboration between researchers at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. and the University of Liege in Belgium described how cortical activation was detected in the fMRI examination of a 23-year-old woman in a persistent vegetative state when she was asked to imagine she was playing tennis.

Though this line of investigation indicates comatose patients can sometimes cognitively react to outside stimulus, other studies show that behavioral tests gauging the patients' status are often inaccurate. Colleagues of Schwarzbauer's at Cambridge, including Adrian Owen, PhD, and his team, found that one in six patients rated on the Glasgow Coma Scale are misdiagnosed -- based on their visual ability, verbal responsiveness, and motors skills.

"That is why we want to use functional brain imaging to see what is happening inside the brain," Schwarzbauer, chair of neuroimaging at the University of Aberdeen, said. "We are attempting to use fMRI to noninvasively determine the actual state of consciousness for patients apparently in comas or vegetative states."

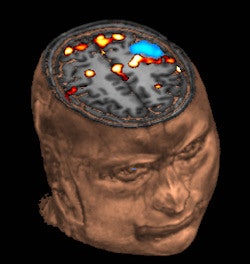

| A 3D volume rendering of blood-oxygen-level-dependence MRI produces a distinct activation in a healthy volunteer. Such imaging may lead to better assessments of sensory capabilities of comatose patients. Image courtesy of the University of Aberdeen. |

The University of Aberdeen, and neighboring healthcare institutions in this city of 208,000 residents, have provided Schwarzbauer with resources to pursue his goal. The new Aberdeen Coma Science Group has recruited neuroscientists, psychologists, physicists, and mathematicians for the multidisciplinary effort.

Comatose patients potentially available for examination are treated at Royal Aberdeen Infirmary. The National Health Service Grampian designated the hospital to provide initial treatment for all severe head trauma cases in northeastern Scotland. This means more patients of interest to the coma science group are treated there than at any health facility in Edinburgh or Glasgow, which have numerous hospitals.

The imaging suite at Royal Aberdeen is also an asset. It is equipped with a 3-tesla MRI system, PET/CT scanners, and SPECT scanners, all capable of sophisticated brain imaging, Schwarzbauer said.

Dr. Helen Gooday and her staff at the neurological rehabilitation center of Woodend Hospital will play a particularly important role because of their experience with patients in vegetative states and extended comas, Schwarzbauer said.

SINAPSE, a consortium of six Scottish universities that are pursuing advanced brain imaging research with financial help from private industry, supports the project.

Schwarzbauer is in the midst of an initial round of fMRI activation studies on healthy volunteers to validate techniques under various conditions in Aberdeen before applying them to research.

|

| Christian Schwarzbauer, PhD, chair of neuroimaging at the University of Aberdeen, has established the Aberdeen Coma Science Group to apply functional imaging to the study of comatose patients. Image courtesy of the University of Aberdeen. |

The coma science group is planning a cortical activation study that builds on the "tennis playing visualization" study suggesting fMRI can show cognition in comatose patients. A second round of studies will test vision, hearing, and language to determine whether stimulating those senses will activate brain tissues associated with their regulation. A third series will focus on functional connectivity when brain activation is not observed.

"We want to see if signal changes observed in one region of the brain are synchronized with changes in different brain areas," Schwarzbauer explained. "Based on the patterns we see, that will hopefully give us an idea about at what level the brain is still able to communicate internally," he said.

Schwarzbauer also plans on collaborations with other brain imaging researchers who use fMRI to study vegetative states and consciousness. They include Owen, Dr. Steven Laureys, PhD, at the University of Liege in Belgium, and researchers at Max Planck Institute at Leipzig and Tuebingen, Germany.

Over time, the coma science group's work may return the University of Aberdeen to the top tier of medical imaging science. Despite its importance to local medical practice, the university has not made a major contribution to the advancement of medical imaging since gaining distinction in the late 1970s by building one of the world's first whole-body MRI scanners.

"There haven't been many papers in Science and Nature from here in a long time, but, hopefully, that will change," Schwarzbauer said. "This could really give a boost to imaging."