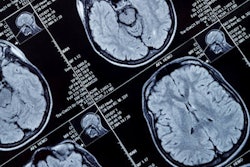

Advanced MRI sequences have revealed that a significant proportion of active elite rugby players experience changes in brain white matter from their participation in the sport, according to research published online on 22 July in Brain Communications.

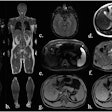

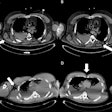

After evaluating 44 adult elite rugby players with diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI) and susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), researchers from the U.K. found either axonal injury or diffuse vascular injury in nearly one-fourth of the players, as well as abnormalities of fractional anisotropy and other diffusion measures in nonacutely injured patients. In a subgroup of 18 patients who were followed over time, volumetric MRI showed unexpected mean reductions in white-matter volume.

"Our research using advanced magnetic resonance imaging suggests that professional rugby participation can be associated with structural changes in the brain that may be missed using conventional brain scans," said senior author Prof. David Sharp of Imperial College London (ICL) in a statement.

The study involved 41 male players and three female players between July 2017 and September 2019. Of the players, 21 were assessed shortly after sustaining a mild traumatic brain injury.

The researchers used DTI to assess for diffuse axonal injury and SWI to evaluate for diffuse vascular injury. These findings were then compared with control subjects consisting of 15 athletes in noncollision sports and 32 nonathletes.

The investigators found that 10 (23%) of the rugby players had evidence of either axonal injury or diffuse vascular injury. These changes were observed in players with and without a recent head injury.

In the 18 players who participated in longitudinal testing, volumetric structural imaging revealed abnormal mean changes in white-matter volume between the baseline and follow-up MRI scans performed an average of a year later. These changes were not related to self-reported head injury or neuropsychological test scores and might indicate excess neurodegeneration in white-matter tracts affected by injury, according to the researchers.

"The implications on an individual level of the brain changes associated with elite rugby participation are unclear, although obviously it is concerning to see these changes in some of the players' brains," said first author Karl Zimmerman, a PhD student and researcher at ICL, in a statement. "It is important to note that our results in adult professional rugby union and league players are not directly comparable to those who play at local or youth levels. The overall health [benefits] of participating in sports and physical exercise have been well established including the reduction in mortality and chronic diseases such as dementia."

Notably, brain function assessments such as memory tests completed by the players found that players with abnormalities in their brain structures did not perform worse than those players without abnormalities.

"Further well-designed large-scale studies are needed to understand the impact of both repeated sports-related head impacts and head injuries on brain structure, and to clarify whether the abnormalities we have observed are related to an increased risk of neurodegenerative disease and impaired neurocognitive function following elite rugby participation," the authors wrote.

Funded by the Drake Foundation, the research was performed by Imperial College London in collaboration with the University College London. Additional support was provided by the National Institute for Health Imperial Biomedical Research Centre in London, the UK Dementia Research Institute, and the Rugby Football Union.