Always be aware of endometriosis as a possible cause for acute symptoms in a woman of reproductive age and make sure you ask for the patient's history. That's one of the take-home messages from a group of experts with extensive experience in ob/gyn imaging.

"Endometriosis can present with a variety of symptoms -- not always chronic," stated radiologist Dr. Caroline Mandoul and her colleagues at CHU Montpellier. "Keep in mind differential diagnosis -- mostly tumors."

MRI is generally the best imaging modality in suspected cases, and it's important to look for characteristic T1-weighted fat-suppressed (FS) foci. On CT, it's vital to search for stellar, mildly enhanced, infiltrated lesions in suggestive areas. And although an accurate diagnosis is possible with CT, it's a difficult task, they said.

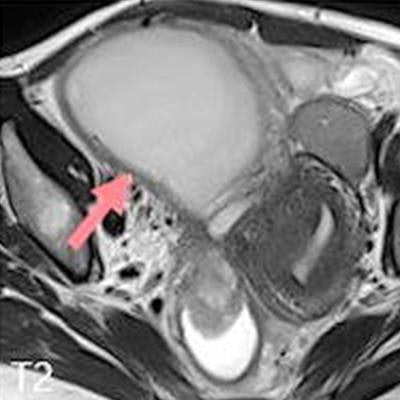

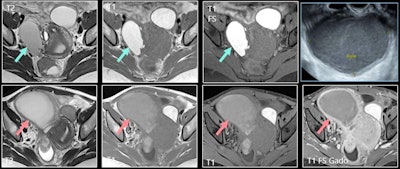

A 39-year-old woman was diagnosed with deep pelvic endometriosis. MRI showed typical endometrioma of right ovary; unilocular cyst with hypersignal greater than fat in T1-weighted image (top row, middle image), persisting in T1-weighted fat-suppressed image (top row, right image) and with shading in T2 (top row, left image). Patient presented several months later with pelvic pain, fever, and hyperleukocytosis. Increase in size, loss of shading on T2 (bottom row, left image), loss of hyperintensity on T1-weighted fat-suppressed image, and thick, enhanced wall were consistent with infected endometrioma. Ultrasound-guided drainage led to removal of 250 cc of pus (top right). All figures courtesy of Dr. Caroline Mandoul and RSNA 2020.

A 39-year-old woman was diagnosed with deep pelvic endometriosis. MRI showed typical endometrioma of right ovary; unilocular cyst with hypersignal greater than fat in T1-weighted image (top row, middle image), persisting in T1-weighted fat-suppressed image (top row, right image) and with shading in T2 (top row, left image). Patient presented several months later with pelvic pain, fever, and hyperleukocytosis. Increase in size, loss of shading on T2 (bottom row, left image), loss of hyperintensity on T1-weighted fat-suppressed image, and thick, enhanced wall were consistent with infected endometrioma. Ultrasound-guided drainage led to removal of 250 cc of pus (top right). All figures courtesy of Dr. Caroline Mandoul and RSNA 2020.Endometriosis is a relatively common disease, having an estimated prevalence of between 5% and 20% in women of reproductive age, and radiologists must know about the acute complications of endometriomas, the group explained in an RSNA 2020 e-poster for which they received a certificate of merit.

Infection and hemorrhage

Cases of infection are rare, being present in about 2% of cases. There may be an association between pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis, but often infection gets overlooked because of chronic pain in endometriosis. It occurs spontaneously by the ascending route, hematogenous spread, or extension from adjacent bowel, and by direct inoculation after a surgical procedure or transvaginal aspiration.

Many patients present with progressive lower abdominal pain and fever, elevated C-reactive protein, and leukocytosis, they added.

The sonographic appearance may be similar to an uninfected endometrioma. On MRI, there is an increase in the size of a known endometrioma, as well as a reduced typical endometriotic signal (loss of hyperintensity in T1-weighted FS imaging and loss of shading in T2). Other signs are marked restriction of diffusion with very low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, thick enhanced walls, and pelvic stranding.

"Superinfected endometriomas lose their typical endometriotic MRI signal and show marked restriction of diffusion with low ADC values," noted Mandoul and colleagues.

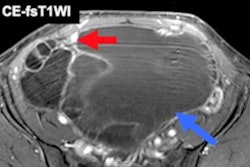

Hemorrhage is also rare, occurring in approximately 2% of cases and comprising fissuration or rupture of an endometrioma. On MRI, a hemoperitoneum with markedly hyperintense fluid may be seen on fat-suppressed T1-weighted images (i.e., the same signal as the endometrioma). Acute hemorrhage caused by other conditions usually has intermediate or slightly high signal intensity on T1-weighted FS images. Distorted shape of the endometrioma is another aspect to look out for.

"Fat-suppressed [T1-weighted] images are mandatory," the authors pointed out. "Markedly hyperintense peritoneal fluid is characteristic of rupture of an endometrioma. Fissurated or ruptured endometrioma show a distorted shape."

Other pearls

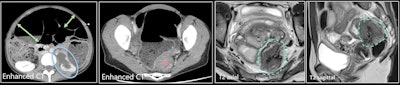

In the acute setting, noninvasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis can be achieved with CT or MRI. CT provides a positive diagnosis of obstruction and/or perforation. An eccentric noncircumferential nodular thickening of the bowel wall responsible for small or large bowel obstruction on CT in a woman of reproductive age is suggestive of endometriosis.

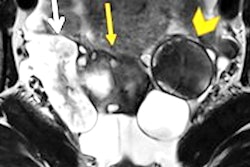

A 39-year-old woman (different from previous figure) with acute clinical intestinal obstruction. Contrast-enhanced CT (first two images) shows small and large bowel distension (green arrows), longstanding left urinary obstruction (blue circle), and mechanical obstruction with rectosigmoid mass (red star). MRI was performed after surgical decompression by colostomy. T2 axial and T2 sagittal images show stellar retractile hypointense T2 mass of the Douglas pouch with colic muscular thickening. Endometriosis of the torus extends transmurally to the rectosigmoid, with stenosis and left ureter involvement.

A 39-year-old woman (different from previous figure) with acute clinical intestinal obstruction. Contrast-enhanced CT (first two images) shows small and large bowel distension (green arrows), longstanding left urinary obstruction (blue circle), and mechanical obstruction with rectosigmoid mass (red star). MRI was performed after surgical decompression by colostomy. T2 axial and T2 sagittal images show stellar retractile hypointense T2 mass of the Douglas pouch with colic muscular thickening. Endometriosis of the torus extends transmurally to the rectosigmoid, with stenosis and left ureter involvement."Preoperative diagnosis of appendicitis caused by endometriosis is difficult and therefore rarely made," they said. "Ultrasound of the right iliac fossa with a high-resolution linear transducer is probably the best imaging modality."

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis (or noninvasive implants) is a form of pelvic endometriosis to keep in mind. Implants are well recognized on laparoscopy, being described as black, white, or red, depending on the degree of fibrosis, scarring, and hemorrhage within the lesion. Superficial lesions are usually difficult to detect by imaging, though hemorrhagic implants can be seen as hyper T1-weighted FS foci on MRI.

"It is well known that patients with endometriosis have an inflammatory process within the peritoneal cavity," Mandoul and colleagues explained. "In our case, an acute process of inflammation of the peritoneal implant was responsible for acute right lower quadrant pain, a differential diagnosis for appendicitis, and salpingitis."

The possibility of inflammatory peritoneal endometriosis can be considered in cases of isolated peritoneal fat stranding with a stellar mass in a woman of reproductive age.

Urinary and neural complications

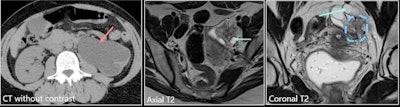

The ureter is a common site of urinary tract endometriosis. It originates from adjacent disease of the ovary, broad ligaments, or uterosacral ligaments, and presents as irregular hypointense nodules on T2-weighted images. Extrinsic disease may be suspected when the interface of fat between the nodule and ureter is no longer visible. It is really important to mention it to the surgeon, and it may require the presence of a urologist during the procedure, the authors emphasized.

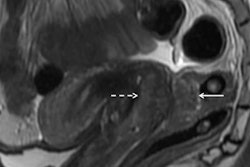

A 42-year-old woman presented with acute left lumbar region pain. She had no history of endometriosis. Left image: CT without contrast shows left hydronephrosis. Middle image: Axial T2 shows dilated left ureter. Right image: Coronal T2 shows retractile, stellar periureteral mass responsible for kidney obstruction. There was no hemorrhagic signal. The suggestion was deep infiltrative endometriosis. A nephrectomy was performed because of the complete loss of left kidney function, and it confirmed the diagnosis of left ovarian and parametrial endometriosis, with a normal ureter.

A 42-year-old woman presented with acute left lumbar region pain. She had no history of endometriosis. Left image: CT without contrast shows left hydronephrosis. Middle image: Axial T2 shows dilated left ureter. Right image: Coronal T2 shows retractile, stellar periureteral mass responsible for kidney obstruction. There was no hemorrhagic signal. The suggestion was deep infiltrative endometriosis. A nephrectomy was performed because of the complete loss of left kidney function, and it confirmed the diagnosis of left ovarian and parametrial endometriosis, with a normal ureter.Involvement of the different ureteral layers is very difficult to determine on imaging. Also, endometriosis symptoms may be secondary to upper urinary tract involvement (flank pain, obstruction), and always check for ureteral and or renal dilation (risk of renal failure if untreated)

Furthermore, MRI is very helpful to investigate neural involvement and to rule out differential diagnoses such as lumbar disk disease, spondylotic nerve root compression, primary neural tumor, and metastasis. Muscle denervation signs (mostly atrophic changes) or even bone reaction (cortical sclerosis) can be demonstrated on MRI.

"MRI is the best tool for the diagnosis of neural endometriosis, especially the T1-weighted fat-suppressed sequence," the researchers wrote. "MRI appearances include solid spiculated nodules, complex cystic masses and cystic lesions with thick walls, with peripheral T2 fat-suppressed hyperintensity and contrast enhancement due to local edema."

Cystic components often show typical endometriotic signal: T2 hypointensity and T1 and T1 fat-suppressed hyperintensity, they concluded.