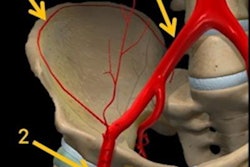

Patient-specific 3D-printed models based on pelvic CT scans improve clinicians' understanding of complex pelvic anatomy and their ability to plan surgical repair for urethral injuries more than conventional imaging, according to a study published online in the Turkish Journal of Urology.

Even for the most experienced surgeons, certain aspects of urethroplasty can be challenging due to the unpredictable nature of many urethral injuries and the limited visibility of relevant anatomy on conventional diagnostic images, noted co-authors Drs. Pankaj Joshi and Sanjay Kulkarni from the Kulkarni Reconstructive Urology Center in Pune, India. Kulkarni is also president of the International Society of Urology.

The physicians created individually tailored 3D-printed models and used them to help manage the cases of several patients with a pelvic fracture who also sustained a urethral injury. They found that the models improved visualization of key anatomical structures and ultimately helped direct the proper course of treatment.

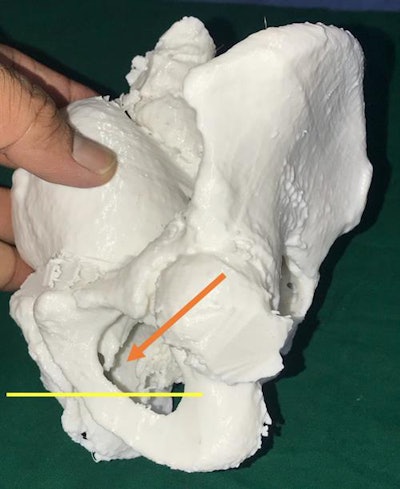

3D-printed model of the pelvis based on patient CT scans. A lateral view shows the posterior urethra (arrow) above the inferior margin of the pubic bone, indicating a need for surgical repair. All images courtesy of Dr. Pankaj Joshi.

3D-printed model of the pelvis based on patient CT scans. A lateral view shows the posterior urethra (arrow) above the inferior margin of the pubic bone, indicating a need for surgical repair. All images courtesy of Dr. Pankaj Joshi."3D printing of pelvic fracture urethral injuries is feasible using the CT scan data," they wrote. "It could be useful as a training tool for urologists or can be used [to resolve] complex cases."

A posterior view of the 3D-printed model showing the posterior urethra in relation to the inferior margin of the pubic bone.

A posterior view of the 3D-printed model showing the posterior urethra in relation to the inferior margin of the pubic bone.3D-printed pelvic models

Roughly 10% of pelvic fractures involve an injury to the urethra, which generally calls for surgical repair after urinary drainage, according to the authors. The standard way to plan the urethroplasty is to examine the urethra on x-rays, or on CT and MRI scans for especially intricate injuries involving the proximal end of the urethra.

However, conventional imaging offers poor visibility of the urethra, making it difficult for physicians to determine its precise positioning, they continued. This, in turn, limits their capacity to determine the ideal surgical approach beforehand.

Joshi and Kulkarni thus turned to 3D printing technology to provide clinicians with a tangible, 3D view of pelvic fractures in hopes of bolstering the ease and efficiency of surgical repair (Turk J Urol, 14 November 2019).

For their pilot study, the researchers acquired CT scans of 10 patients who had a urethral injury after pelvic fracture and were scheduled for surgical treatment at their tertiary referral center. The center is currently home to one of the largest databases of pelvic fracture urethral injury repairs, with 1,307 urethroplasties, according to the authors.

The group segmented and processed the CT scans using 3D reconstruction software and then generated a separate anatomical model for each of the patients using a 3D printer (Ultimaker). The models were composed of acrylic fibers and took approximately 20 hours to make.

Compared with conventional 2D images, the 3D-printed models allowed the surgical team to better understand several aspects of the patients' urethral injuries:

- The distance between the urethra and the rectum

- The length of the urethral gap

- The direction of the urethra's displacement

- Spatial relationships between the urethra and nearby structures

- The nature of rare injuries such as bulbar urethral necrosis and rectourethral fistula

"These models help us understand the ... exact displacement of the posterior urethra, its relation to the pubic bone, its relation to the rectum, displacement from the midline, and also the status of the anterior urethra," the authors wrote.

'A step ahead'

In certain cases, the 3D-printed models also directed the surgical team's decision-making concerning the best way to repair the injuries and the patients' need for pubectomy. For example, the 3D-printed pelvic model of one female patient revealed that her incontinence was a result of hypospadia near the opening of her urethra. This information encouraged the surgical team to make a distal pedicled labial flap tube for the patient to restore continence.

The researchers also conducted a survey of 30 visiting urologists that asked if they considered the patient-specific 3D-printed pelvic models useful for preoperative assessment of urethral injuries. The physicians unanimously agreed that the models appeared to be "extremely useful," especially in helping them decide whether or not the patient required inferior pubectomy to bridge the gap between the two ends of the urethra.

In addition, the urologists also stated, albeit subjectively, that studying the 3D-printed models rather than conventional images during presurgical planning would likely reduce operating times.

Integrating 3D printing into the management of urethral injuries could "help in surgical planning and making urethroplasty easy, a step ahead of conventional imaging," Joshi and Kulkarni wrote.

Yet they acknowledged that the 3D printing technique is not without its limitations, including clinicians' limited access to 3D printers at many institutions and the high cost and long processing time required to construct the models. For their study, the researchers decided to scale the patient-specific 3D-printed models down to 80% to be able to manufacture them more quickly.

Regarding future research, Joshi and Kulkarni plan to create 3D-printed pelvic models using bioink that more closely resembles the texture of human bone to allow physicians to simulate pubectomy and similar surgeries and, potentially, improve surgical outcomes.