Imaging is on the "cusp of a revolution," according to a pan-European group of researchers who have studied the mounting evidence supporting the use of different imaging modalities in both early (prodromal) and established dementia. Their personal view was published online on 26 August by Lancet Neurology.

"Within 10 years we will see new imaging techniques, software, and biomarkers that will assist specialists in diagnosing patients early and aid the development of much-needed treatments," co-author Dr. Chris Fox, professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of East Anglia, U.K., told AuntMinnieEurope.com.

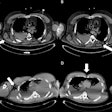

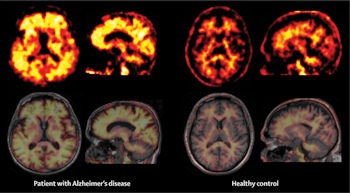

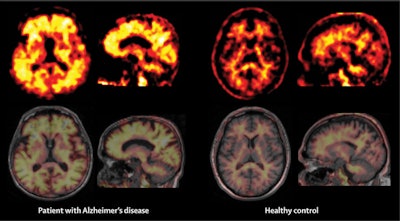

Representative amyloid PET images of a patient with Alzheimer's disease and a healthy control obtained with the F-18 labelled tracer Florbetaben. Nonspecific white matter binding, as seen in the healthy control, spreads to the neocortical gray matter in the patient with Alzheimer's disease as a sign of cortical amyloid β load. Image courtesy of the Lancet Neurology.

The article, of which the lead author is Dr. Stefan Teipel from the DZNE (German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases) in Rostock, Germany, emphasizes the need for an up-to-date and robust assessment of the status of imaging in this field.

"The strongest candidates in my view are structural MRI and FDG-PET," Fox said. "MRI has some advantages over other options in that it shows vascular changes, atrophy, and shrinkage; markers are also being developed with functional MRI that show changes in activity. But at the present time, FDG-PET holds most promise of breaking into clinical practice due to the sheer number of trials using FDG-PET imaging."

Furthermore, the accumulation of evidence suggests that certain Alzheimer's-related abnormalities can be identified on images and could enable detection of disease prior to clinical signs manifesting. These findings have fuelled clinical interest in the use of specific imaging markers for Alzheimer's to predict future development of dementia in patients who are at risk, Fox added.

"There is significant underdiagnosis [of Alzheimer's] in various countries. Imaging is a key part of the diagnostic process, and of particular interest is pre-illness understanding of dementia," he stated, noting that a critical unmet need exists to both diagnose disease accurately and predict the extent of a patient's disease.

Advances in imaging can aid understanding of the sequence of pathogenic events during the prodromal (predementia) stage and help determine what can be done before the downward spiral of clinical symptoms start, according to Fox. Such developments would also help to determine which patients benefit from interventions, for example nutritional supplements or pharmacological treatments.

Special patient groups

Certain difficult-to-diagnose groups are of particular interest, including working-age patients who have atypical presentations.

"They are a quandary to clinicians because sometimes a CT or basic MRI might appear normal, but there is dysfunction present," Fox explained. "Specialized imaging as highlighted in the [Lancet] paper can unlock this and can show amyloid and Tau imaging, which is relatively new."

.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) We need greater standardization in how to interpret scans and better guidance on which imaging outcomes to use in clinical trials, according to Dr. Chris Fox.

We need greater standardization in how to interpret scans and better guidance on which imaging outcomes to use in clinical trials, according to Dr. Chris Fox.Currently in the U.K., the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which acts as a health watchdog, advises about the use of CT and MRI as imaging modalities suitable for the diagnosis of dementia. In addition, PET imaging is used in certain larger centers with a wider range of facilities.

"Most places consider CT or MRI, but anything else is largely unavailable," Fox said. "There might be an argument to say that MRI above 3-tesla is as good and better value for money. We have a 15-tesla machine in Cambridge that provides a better image, but the downside is that it heats up the brain and uses a lot of power. It's also expensive and we are still uncertain as to how best to interpret 15-tesla images versus 3-tesla images."

Fox would like to see much greater access to different imaging modalities beyond MRI and CT, if the evidence supports it. Other modalities might include PET, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), or other combinations of modalities. Different imaging markers have different value with respect to highlighting pathological changes, and the accuracy of predicting an individual's clinical outcome.

"Amyloid plaques are useful markers, seen on PET imaging, and they can help increase diagnostic accuracy, despite not every case of dementia being amyloid positive," he added.

Vascular changes in dementia are also visible on imaging. At the moment, imaging can show ischemia in a 70-year old, but it's unclear whether this makes it vascular dementia, Alzheimer's, or mixed. Every option is possible and correct, Fox pointed out, highlighting the even greater need for more sophisticated imaging technology.

Ideally, for an intervention to have maximum effect, early signs of dementia need to be better understood and characterized. Studies are ongoing that look at mild cognitive impairment, a predementia, threshold condition, and aim to better understand this condition and which cases progress to dementia, and which cases do not. The conversion rate to full-blown dementia is around 12% to 20% per year, he commented.

If someone, particularly a younger person, is given a diagnosis of Alzheimer's, it can lead to loss of a job, loss of a driving license, marital breakdown, and debt, but the evidence to date suggests that despite such problems people still want to know the diagnosis, Fox said.

Finally, he stressed the need for both greater standardization in how to interpret scans, and for more guidance on which imaging outcomes to use in clinical trials.

"This would help us design better trials, which will lead to a breakthrough. We also need better software and continued development of the hardware -- MRI, for example, and the ability to interpret these images too," he concluded.