Amid rising demand for cardiac imaging and rapid development of technology, cardiac imaging trainees are often squeezed for time as they try to develop the necessary skills to do their jobs.

Still, there are several essential ingredients for successful training in cardiac imaging that will equip facilities for the future, according to Dr. Francesca Pugliese, PhD, consultant in advanced cardiovascular imaging and senior clinical lecturer at Barts London Chest Hospital. She enumerated on these requirements in a talk at ECR 2017.

"It's about being comprehensively exposed, it's about incorporation of clinical information, and it's about imaging findings not only of the cardiac test, but also other tests," Pugliese said. Studies show that training needs to be hands-on, and it's vital to allow the trainee to recognize what is reliable versus what is less reliable, and more importantly what is clinically relevant and not so relevant to change patient management, she added.

More test possibilities, more reasons for tests

Dr. Francesca Pugliese from Barts London Chest Hospital.

Dr. Francesca Pugliese from Barts London Chest Hospital.The need for cardiac imaging is growing as European radiology adopts the technology in a wider variety of clinical contexts, but hospitals are finding themselves increasingly understaffed. The more widespread availability of emerging methods, such as T1 mapping in MRI and fractional flow reserve CT, is helping drive demand upward, Pugliese said.

Yet there are many factors limiting growth, including cost considerations, human resource considerations, and training requirements. From a credentialing standpoint, there is individual certification and lab accreditation, so who can teach what to whom becomes an important question. Lining up all of the elements for a great training program is a difficult endeavor. And you can't teach with a bad product.

The focus should be on the patient and the clinical utility of the images, Pugliese said. For that to happen all the steps along the way from acquisition to interpretation must be optimized.

"The protocols need to be right, the images need to be right, and the procedures need to be safe, including the use of pharmacological stressors, high magnetic fields, and all that," she noted.

The new imaging tests must compare favorably with traditional tests, and they must demonstrate proper clinical utility for changing patient management, she said. The right protocols and sequences need to be followed to minimize artifacts.

In image acquisition, the technology and the operator are coequal players, she said. Humans are still responsible for a large share of the overall quality of cardiac imaging, anatomy and disease-related changes, developing differential diagnoses, putting radiology findings into a clinical context, recognizing artifacts and finding ways to minimize them, and developing software and workstation skills, Pugliese said.

Furthermore, newer technologies often are the better ones, and a landmark 2009 study established that lack of experience in cardiac imaging was associated with higher patient radiation doses, along with kV settings and dose-reducing technologies, she continued.

In interpretation as well as acquisition, humans and technology both contribute to quality imaging. Technology offers computer-aided detection, workflow aids, image quantification, and artificial intelligence. Operators interpret the anatomy and note disease-related changes, put radiological findings in the clinical context, and communicate the findings via reporting, she pointed out.

Steep path to expertise

Getting cardiac imaging experience isn't always easy, however. Training faces a wide range of challenges, including trainees' limited clinical exposure to patients with cardiac disease, limited exposure to CT and MR technology and their applications, limited access to imaging infrastructure and data, and not least, the lack of a multidisciplinary approach to training.

"Some students have limited time for self study, to attend courses, ask questions, and receive feedback, unless the training happens in specific area of the curriculum or in a focused fellowship, which is a lucky situation," she said.

Core training guidelines count the number of mentored cases of mixed pathology as a rough measure of competence: 50 for the basic level, 100 for intermediate, and 150 for advanced. Along with practice come courses and lectures and other knowledge-building exercises.

Is the core curriculum sufficient to create qualified readers? A few years ago Pugliese and colleagues performed a study of cardiac imaging training on students with no prior experience during a one-year fellowship in which they examined 10 to 15 coronary CT angiography (CTA) cases a week. Three of the fellows were radiologists and one was a cardiologist. They reached level 1 -- 50 cases -- at four weeks; level 2, 100 cases, in eight weeks; level 3, 300 cases in six months; and level 4, 600 cases, in one year.

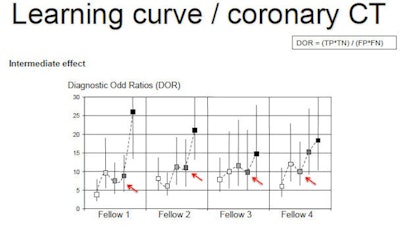

At the end of the process the four fellows had a sensitivity of about 80% compared with angiography. However, the acquisition of skills wasn't linear. Midway through the year, sensitivity and specificity dropped, only to recover later on toward the end of training, creating a steep learning curve at the end.

During the learning process there was a dip at around the six-month, 300-case point, she said, and the diagnostic odds ratio fell for most fellows only to pick up again by the end of the year. Of course, the study was only a test of practical knowledge, without focus on clinical content, rendering the setting somewhat artificial. But the drop in diagnostic accuracy was notable.

Image republished with permission of the RSNA from Radiology, May 2009, Vol. 251:2, pp. 359-368.

Image republished with permission of the RSNA from Radiology, May 2009, Vol. 251:2, pp. 359-368.Understanding the patient experience

In a 2005 discussion of training guidelines published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a multidisciplinary writing group noted that "adhering strictly to [training] standards is less important than understanding deeply what is happening to the patient," Pugliese said.

That is, the quality of the clinical experience is paramount. Key to success are exposure to hands-on clinical training, and understanding what factors are important for altering patient management and which are not. A wide mix of pathologies, a substantial workload, and having time to learn are also paramount, she said.

To this end, the European Society of Cardiac Radiology (ESCR) offers a range of scholarships and fellowships. The ESCR has an MR/CT registry that trainees may use, and the EuroCMR registry covers MRI images. Finally, the European Board of Cardiac Radiology offers accreditation opportunities.

Credentialing in cardiac imaging, both lab accreditation and individual certification, is a useful solution to many of the practical limitations of cardiac training, and may be important for setting up a training program, and helps define the critical questions about who is permitted to do what and when, Pugliese said. The aim is to standardize training at a high level across Europe.

Imaging technology continues to improve, and it gives new opportunities so images can be more precise and more complex, which means problems can be looked at in a more precise way, and "we can look at more complex problems," she said. Similarly, the core curriculum will continue to evolve in a dynamic way.