A research group from the University of Cambridge in the U.K. has found evidence on MRI scans that the brain compensates for age-related deterioration by enlisting other areas to help with brain function and maintain cognitive performance.

The study findings shed light on how our brains handle cognitive decline as we age, wrote first author Ethan Knights, PhD, investigator scientist and Cambridge Centre for Ageing and Neuroscience (Cam-CAN) data manager at the Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, and colleagues. The team's results were published on 6 February in eLife.

"Our results in the cuneus [a small lobe in the occipital lobe of the brain] represent the most compelling evidence to date for functional compensation in healthy aging, with further work needed to determine the precise function of this region in problem-solving tasks like that examined here," they noted. "[Our] data also suggest that specific compensatory neural responses can coexist with inefficient neural function in older people."

The brain atrophies as an individual ages, losing nerve cells and connections that can translate to decreased brain function. But this deterioration varies, with some people maintaining better function than others. One theory as to why this might be is that some individuals' brains enlist other areas of the brain to compensate for deterioration.

"Our ability to solve abstract problems is a sign of so-called 'fluid intelligence' [that is, the ability to solve abstract problems], but as we get older, this ability begins to show significant decline," senior author Kamen Tsvetanov, PhD, said in a statement released by the university. "Some people manage to maintain this ability better than others. We wanted to ask why that was the case -- are they able to recruit other areas of the brain to overcome changes in the brain that would otherwise be detrimental?"

Previous research has shown that fluid intelligence tasks engage what's called the multiple demand network, which involves regions both at the front and rear of the brain. This network's activity decreases with age. Knights and colleagues investigated whether the brain compensated for this decrease in activity, conducting a study that included MR imaging data from 223 adults between the ages of 19 and 87 who had been recruited via the Cam-CAN.

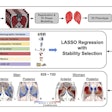

Image showing bilateral cuneal (magenta) and frontal cortex (brown). Courtesy of eLife/University of Cambridge.

Image showing bilateral cuneal (magenta) and frontal cortex (brown). Courtesy of eLife/University of Cambridge.

Study participants were asked to identify the "odd-one-out" in a series of puzzles of varying difficulty while lying in a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner; the researchers measured blood flow to track patterns of brain activity.

Overall, the team found that participants' ability to solve the puzzles decreased with age. But the researchers also reported that in some older people, two areas of the brain showed greater activity and correlated with better performance on the puzzle task: the cuneus, at the rear of the brain, and a region in the frontal cortex.

"Although it is not clear exactly why the cuneus should be recruited for this task, the researchers point out that this brain region is usually good at helping us stay focused on what we see," the statement continued. "Older adults often have a harder time briefly remembering information that they have just seen, like the complex puzzle pieces used in the task. The increased activity in the cuneus might reflect a change in how often older adults look at these pieces, as a strategy to make up for their poorer visual memory."

The study findings suggest new research directions, Knights said. "Now that we've seen this compensation happening, we can start to ask questions about why it happens for some older people, but not others, and in some tasks, but not others," he said. "Is there something special about these people -- their education or lifestyle, for example -- and if so, is there a way we can intervene to help others see similar benefits?"

The complete study can be found here.